The PIANOS framework: Six keys to extract order from chaos

Without continual growth and progress, such words as improvement, achievement, and success have no meaning. – Benjamin Franklin

Imagine a team racing to launch a lifesaving medical treatment into uncharted markets. Each specialist juggles their own tasks while willing and able to jump in and help their teammates at a moment’s notice. To succeed, they must learn together, evolve their methods, and transform uncertainty into a clear pathway forward. In other words, they must extract order from chaos.

In every complex endeavor - from delivering reliable, reusable rocket launches to complex system & software development - balancing creativity with structure is what turns fractured efforts into breakthrough outcomes. This article introduces the PIANOS framework - six interlocking forces that can guide any team from fragmented ideas to sustained progress. You can jump to the description of the framework directly if its rationale is not of interest.

Diagnosis

The Yin-Yang symbol (Figure 1) represents balance and harmony in Chinese philosophy. It illustrates the idea that opposite forces - like light and dark, male and female, or order and chaos - are interconnected and interdependent. Instead of being purely opposing, they complement and complete each other. This situation is an interplay between order and chaos.

The swirling halves show that each force contains a bit of the other (represented by the small white circles), meaning that within darkness, there is light, and within light, there is darkness. Too much order constrains innovation, too little leads to escalating exposure to unmitigated risks.

Adventure lies along the margins (the yellow boundary between regions), as do rewards, both in fulfilling real needs, and in learning how to mitigate the effects of the ever-evolving chaos. This suggests that balancing efforts across this frontier is essential in all aspects of life. But how can this be done when building new things?

“First, the taking in of scattered particulars under one Idea, so that everyone understands what is being talked about… Second, the separation of the Idea into parts, by dividing it at the joints, as nature directs, not breaking any limb in half as a bad carver might.” Plato, Phaedrus, 265D

Such is the nature of building new things; ideas must be elaborated into substance using organizing frameworks with theoretical underpinnings based upon evidence, mechanisms, and track records of useful predictions.

Under traditional thinking, production pulls together all the pieces and assembles them for the user or for mass distribution. To produce these units at scale, the configurations of components, desired product characteristics, and targeted economies of scale determine the appropriate levels of precision and automation for manufacturing, the materials to be used, and the numbers of components to be integrated. In some cases, it is more cost-effective to produce spare parts in the same batches in which the initial parts are manufactured. This ensures adequate and comparable spares are available during the expected life of the system. This essentially equates production to manufacturing.

Instead, throughout my writings, I deliberately use the term production to refer to the mechanisms used to produce any good or service which has value and contributes to the utility required of capabilities. The etymology of the term production links it to the act of bringing something forward into existence. It is derived from the verb producere, with the pro- prefix meaning "forward" and the -ducere suffix means "to lead or bring." Production therefore refers to both acts of unprecedented creation (through the engineering of new things) and manufacturing (assembling previously designed things). Over time, the use of production has also expanded to include the creation of goods, artistic works, and even abstract concepts like ideas and resources like energy. Let’s open the black box of production to see what kind of aids are helpful to orient our exploration.

An alternative approach to organizing endeavors

Existing frameworks all pursue progress towards realizing goals. But none provides a universal structure that combines useful planning with adaptive flow. Further, their prescriptions are often oversold, failing to provide adequate guidance to cover challenging situations that many projects encounter, while being overly prescriptive for straightforward tasks.

I will be writing about my experiences with each of these frameworks in future posts. They can be helpful in some contexts while failing miserably in others. The contextual realities of complexity and uncertainty are often the key differentiators in selecting which approach should be used. But according to the book How Big Things Get Done, there are several key drivers that are differentiate success and failure:

One driver is psychology. In any big project—meaning a project that is considered big, complex, ambitious, and risky by those in charge—people think, make judgments, and make decisions. And where there are thinking, judgment, and decisions, psychology is at play; for instance, in the guise of optimism.

Another driver is power. In any big project people and organizations compete for resources and jockey for position. Where there are competition and jockeying, there is power; for instance, that of a CEO or politician pushing through a pet project.

One might throw up their hands at this insight, saying these contextual aspects are outside one’s control. But people placed in these situations often fail because the situation they are exposed to is unfamiliar to them. They need to be able to practice and learn from mistakes, when presented with these kinds of problems in a safe, ‘off project’ setting. That’s a place where simulations have been used effectively, and that success can be leveraged to these situations, if approached from a common orientation. Rather than forcing people into difficult choices from among these frameworks, we should start from a meta-framework that pulls the best of class from each and provides viewpoints that are complementary and have broad applicability, spanning the range from setting up a lemonade stand to training large language models. Martin Fowler, in his forward to the book Frictionless, describes the crucial ingredients for effective throughput as feedback loops, flow state, and cognitive load:

We can only find out whether we are on the right path by getting rapid feedback. The longer the delay between that blue dot moving on my phone-map, the longer I walk in the wrong direction before realizing my mistake. If our feedback is rapid, we can remain in the second element, a flow state, where we can smoothly and rapidly get things done, improving our products and our motivation. Flow also depends on our ability to understand what we need to do, which means we must be wary of being overwhelmed by cognitive load, whether it comes in the form of poorly structured code, flaky tests, or interruptions that break our flow.

Thus, an alternative framework is offered here that exploits those ingredients and provides an over-arching structure which draws on the best-of-class from each of the traditional control-oriented frameworks. This alternative also offers potential as a universal framework for all work, in the same manner as the word ‘endeavor’ in my writings covers both temporary and ongoing pursuits to professionals (be they engineers, scientists, etc.) and regular dudes doing everyday things. When presented with a robust environment in which agents can rehearse, practice, learn, and build their skills in shaping production, they build confidence for real-world applications, develop better situational awareness, and learn the importance of effective orchestration.

A few requirements for designing such a framework are worth amplifying. Alternative frameworks should:

seek to integrate, rather than replace, current methods

address the shortfalls described with existing approaches

incorporate learning and feedback as the backbone of work

be structurally compatible with simulation implementations to aid in training and practice

enable tailoring guidance to be offered but not mandated

describe mechanisms for data collection to capture performance with minimal user input

be compatible with AI agents to analyze the resulting data and offer guidance about decisions given production states and experiential trends

Introducing PIANOS

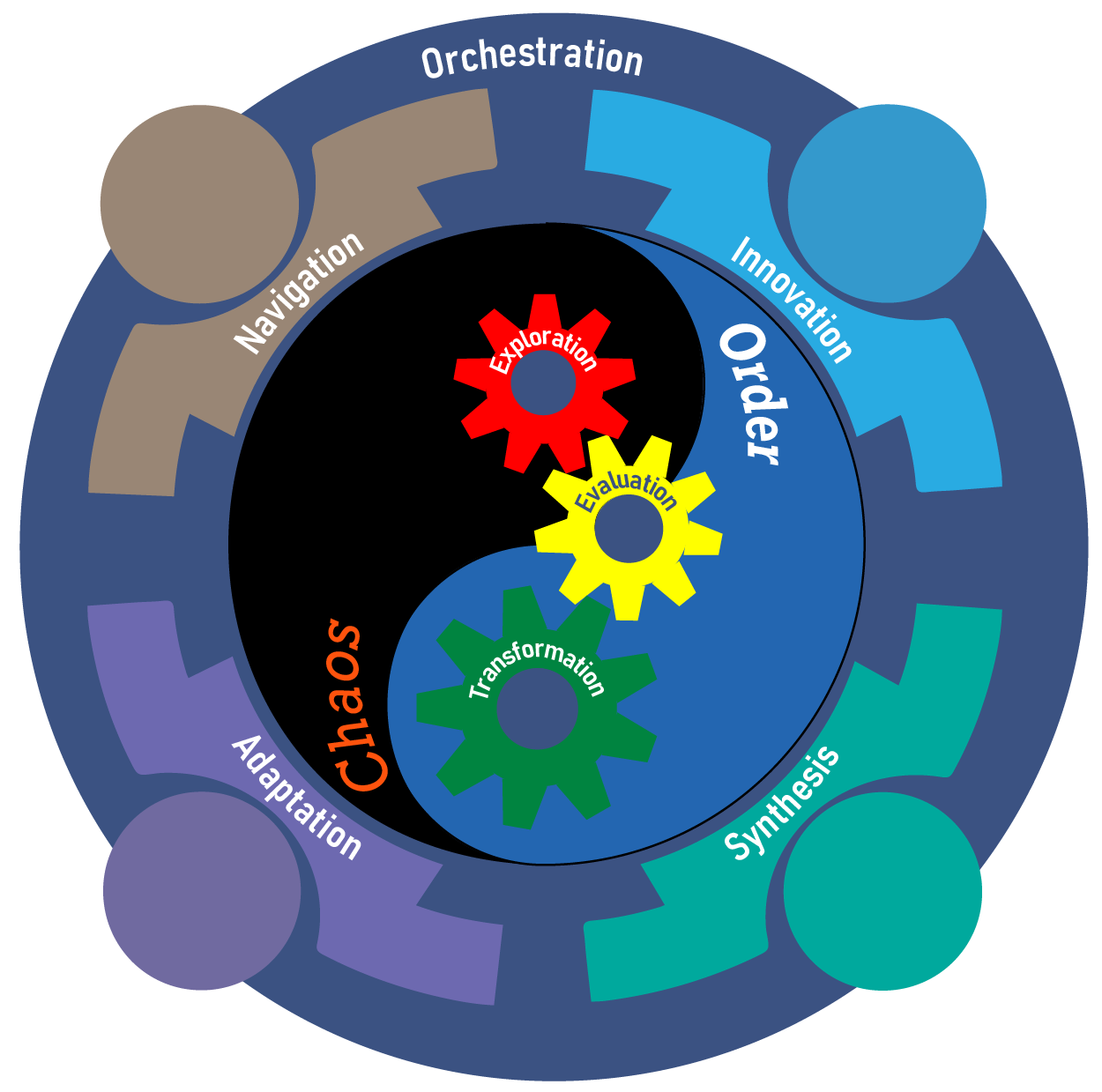

In 1916, Albert Einstein warned against letting old ideas become unchallenged dogma. He argued that real progress means dismantling worn-out concepts and replacing them with systems that better serve our goals. Inspired by that spirit, Figure 3 introduces six interacting viewpoints for organizing the actions necessary to achieve progress for any endeavor, using a representation that is simple enough to serve as an icon for this site, while still communicating several powerful ideas:

Efforts to change our world involve tradeoffs between needing unprecedented innovations within unfamiliar environments and needing disciplined replication of prior successes

Methods employed in such efforts must enable rapid accommodation to changing environments while assuring that adequate fitness is delivered

Methods should also encourage iterative refinements which deliver adequate utility at an acceptable pace for customers

Too much order constrains innovation, and too little risks precious resources

The overall visual concept shown in Figure 3 represents an iterative collaboration among agents pursuing progress. The framework which depicts the essential viewpoints for these agents is captured in the mnemonic “PIANOS”. These viewpoints are conceptual in this representation but will be developed further in the corresponding sections of this blog for each viewpoint:

Production - Production is the primary orientation and is depicted by the inner Ying-Yang symbol in swirling black (depicting chaos) and blue (depicting order). Navigating this boundary involves three interconnected subordinate elements which interact to implement production’s primary architecture:

Exploration - traversing an unfamiliar region of a landscape to gain knowledge about that environment

Evaluation - assessing attributes (characteristics, volume, or value) of a situation within a particular context

Transformation - following a course of action, order, or plan to translate goals and inputs into desired outcomes

Exploration activities are represented by the red gear in the diagram. The yellow gear depicts the evaluation actions necessary to accomplish focused elaboration, verification, and refinement. Finally, the blue gear depicts the successive incubation, transformation, and maturation of capabilities suitable for entry into service. These colors correspond to the classic ‘stoplight’ charts often used in reporting the status of activities.

The interactions among these cogs represent interlocking cycles - with both exploration and transformation activities interdependent on each other and upon their corresponding evaluations - to drive cycles of progress.

Surrounding this cyclical, reentrant production process are five broader forces, each employing a distinctive color symbolizing the agents responsible for guiding these three production gears towards structured progress:

Innovation - researching, experimenting, and engineering novel capabilities and solutions into existence

Adaptation - enhancing the suitability, resiliency, and efficacy of production capabilities within dynamically evolving environments

Navigation - analyzing, elaborating, and exploiting effective pathways to progress over a capability’s lifecycle. Navigation requires active monitoring and balancing resources to:

meet current operational needs through the sustainable use of available capabilities and resources

position future capabilities for addressing the sometimes competing strategic and operational objectives anticipated across future time horizons

Orchestration - collaboration across viewpoints to assure performance, exchange data and control information, and respond to feedback so that intended outcomes can be achieved within environmental constraints; these interactions occur at both the holistic level and in lower-level subsystem through coupling

Synthesis - iteratively configuring, aligning, and tuning existing capabilities to enhance and assure their fitness for use

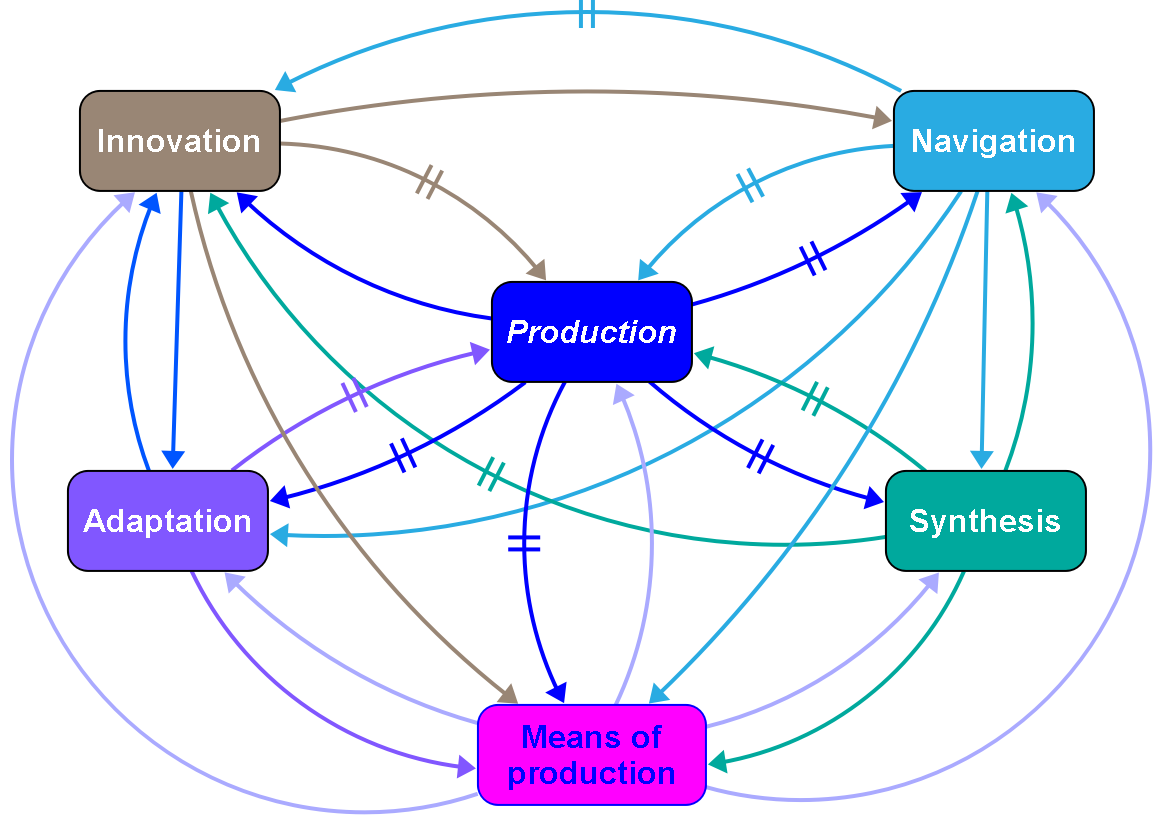

Up until now, these elements properly have been described as viewpoints, and at first blush, may seem like a category scheme, but should instead be thought of as fields as defined in physics:

Each element is a distributed substrate which provides a dynamic continuum across physical subsystems and contexts

Interactions between these elements resemble entanglements, since the state of any one element can influence or constrain another

Changes in one field can ripple across others, even if not directly adjacent, as would be expected in a classical hierarchy

This treatment unifies this layered framework with a physics-inspired ontology, bridging metaphysics, modeling, and systems thinking. It also allows elements to hold multiple potential states until resolved by context (e.g., ambiguous agency until intent is clarified). Finally, it supports modeling of these entanglements, so decisions in one domain can be traced through probabilistic correlations with others, even without explicit diagrammatic connections.

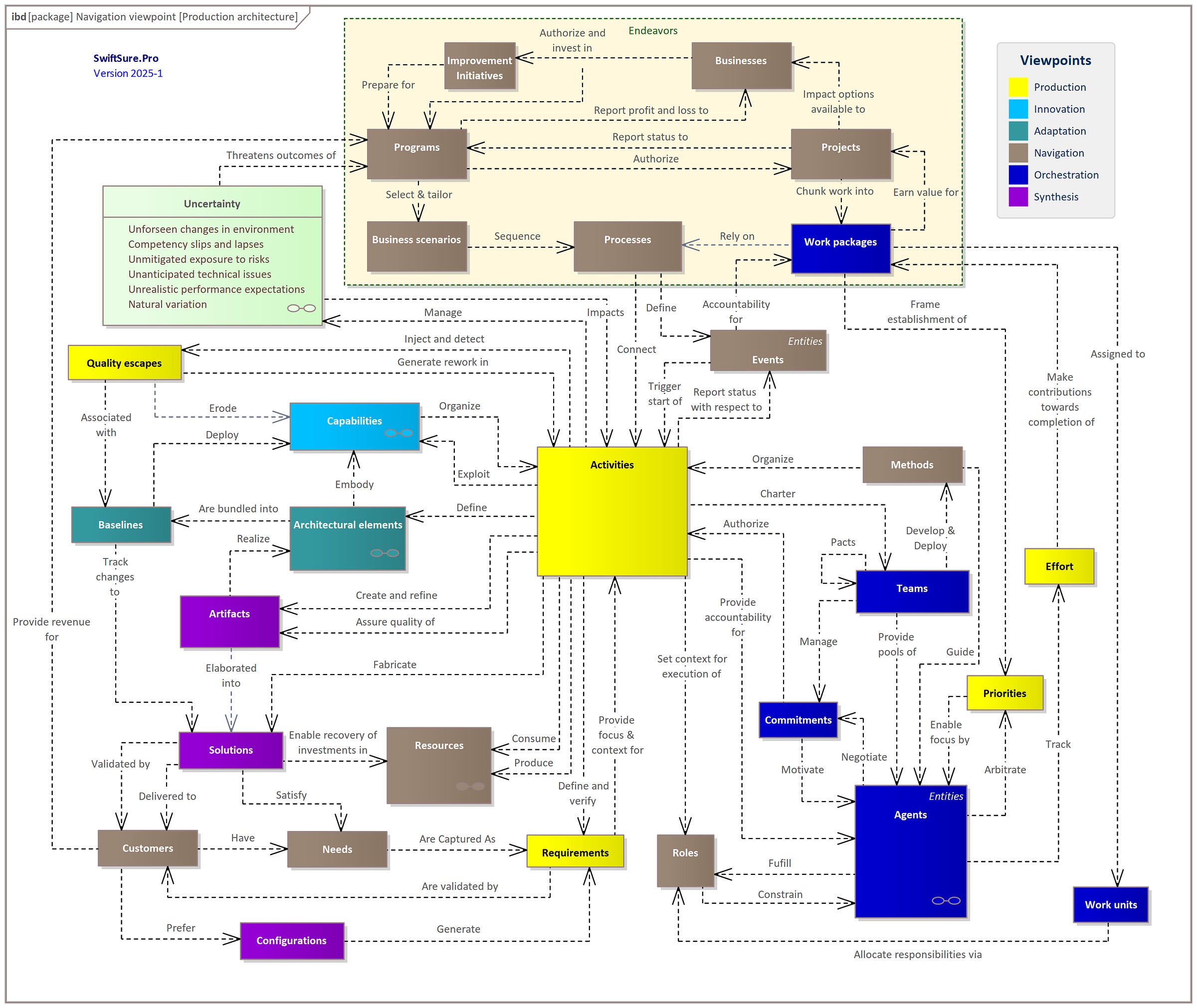

The producers and consumers of critical exchanges

Figure 4 provides an overview of some of the entanglements necessary to integrate these viewpoints into a cohesive whole. There is no start or end to actions here, as this diagram depicts relationships, not flow. These relationships span the full range of endeavors but to keep the representation as simple as possible do not depict the competition, challenges, and constraints imposed by external environments. The dynamics introduced by those dependencies will be developed further in future posts.

This figure exposes my bias for action and belief in the power of comprehensive data and process architectures. Such architectures are sources of clarifying definition when they are properly realized. The relationships impact both the nature of the tools used by communities of practice operating within these viewpoints, and the communications and information management challenges that present themselves in such environments. This structure also lays the groundwork for thinking about opportunities for improvement. But each element must be instantiated with the specific actions appropriate to the context and goals being pursued.

As the figure indicates, activities are always the hubs of value-generating action, and the nature of these activities must be considered carefully, especially with respect to the agents who are to perform them and buy off their implementation. The term ‘agent’ is used rather than ‘people’ (or aggregations of people such as organizations) to reinforce the idea that some functions may be performed by humans and others by algorithms.

In practice, slips and delays from these activities (indicated by double slashes across a flow) play a big part, as indicated in figure 5. These delays represent one of the biggest challenges to proactively address using current techniques.

Analyses of these interactions can help explore the expected outcomes under various initial conditions and operational strategies and can reveal potential gaps in concepts and mental models. As these relationships must be instantiated in a concrete (rather than abstract) context, they will manifest as a more complex and diverse structure than the elements represented in this portrayal.

The power of these forces is evident from their integration:

This framework also provides a reusable structure that - once elaborated - enables comparisons across endeavors from a common structural context. Simulations based upon these ideas thus provide participants with opportunities to perform such tradeoffs, improve their understanding of different situations, and practice alternative responses, all in a safe learning environment. I will unpack this opportunity further as sufficient interest arises.

The PIANOS framework invites teams to embrace the adventure along the yellow boundary of Figure 1 - where innovation meets discipline, and ideas become impact. Whether you're navigating swirling chaos or aligning for breakthrough execution, these six forces offer a structured path forward. Sign up for continuing posts to discover how PIANOS turns fragmented efforts into sustainable progress, helping you orchestrate bold outcomes with clarity, creativity, and purpose. And to continue in this journey of exploring production, the next article in this series is here.