Mistakes, miscommunications, and modifications in production

Success consists of going from failure to failure without loss of enthusiasm. - Winston Churchill

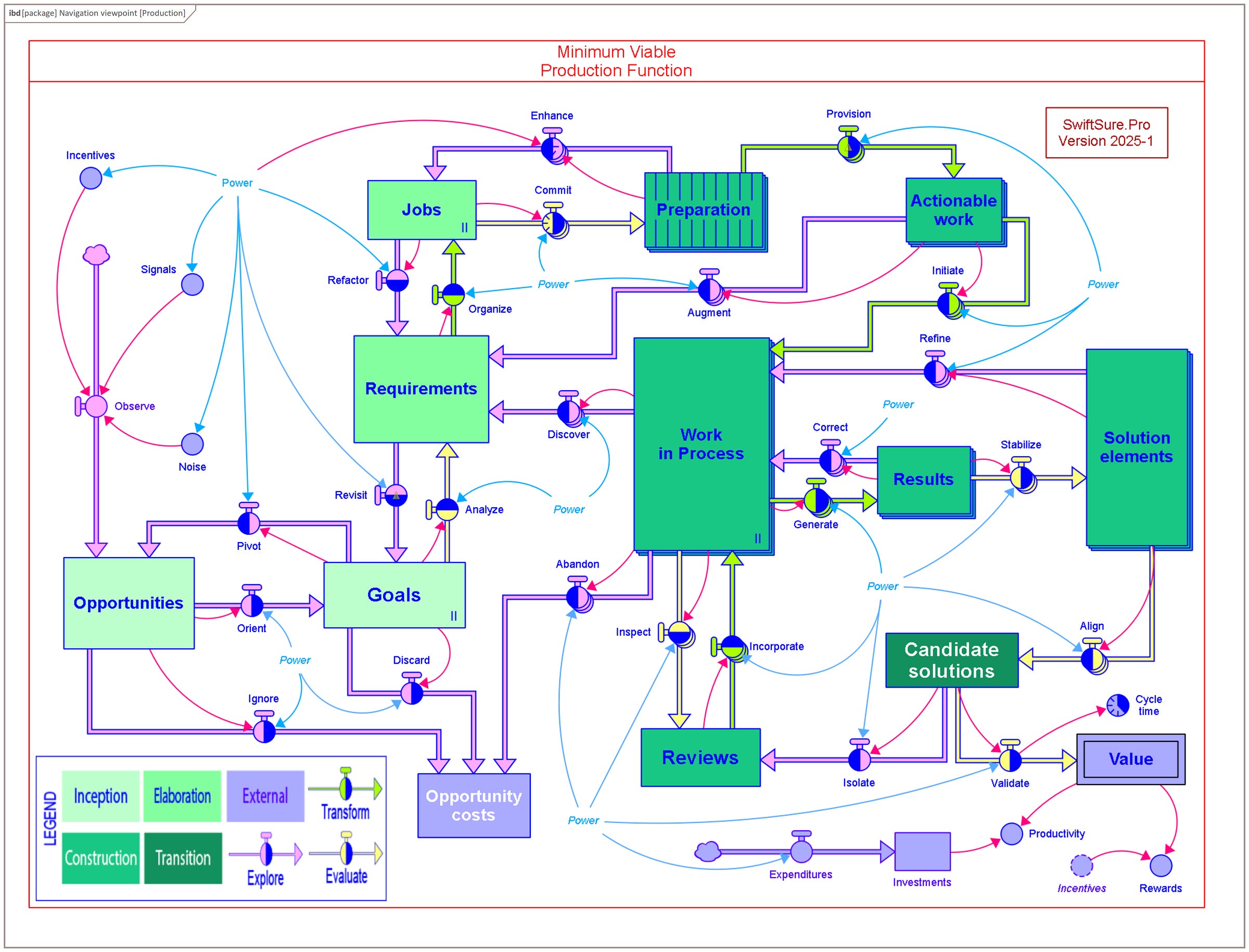

Production transforms inputs into useful outcomes. It requires appropriate organization and coordination of the means of production across its contributing elements. It also must manage the flow of information and resources, analyze operations, exploit feedback to incorporate learning, optimize available capabilities, apply techniques to reduce waste, enhance customer responsiveness, and accelerate work in process across operations. That’s a lot to keep track of, so a map can help.

Economists’ thinking about production has evolved from simple input–output rules to today’s nuanced, multi-factor frameworks. These conceptual shifts include transitioning:

From an engineering metaphor to an economic optimization tool

From fixed technologies to technology itself as an endogenous, evolving factor

From two-factor simplicity to multi-factor, multi-output complexity

From static efficiency to dynamic productivity and innovation analysis

This evolution in thinking originally rested on the concept of production as a black box and examination of what powers it. Let’s open this box and see what’s inside.

Means of production

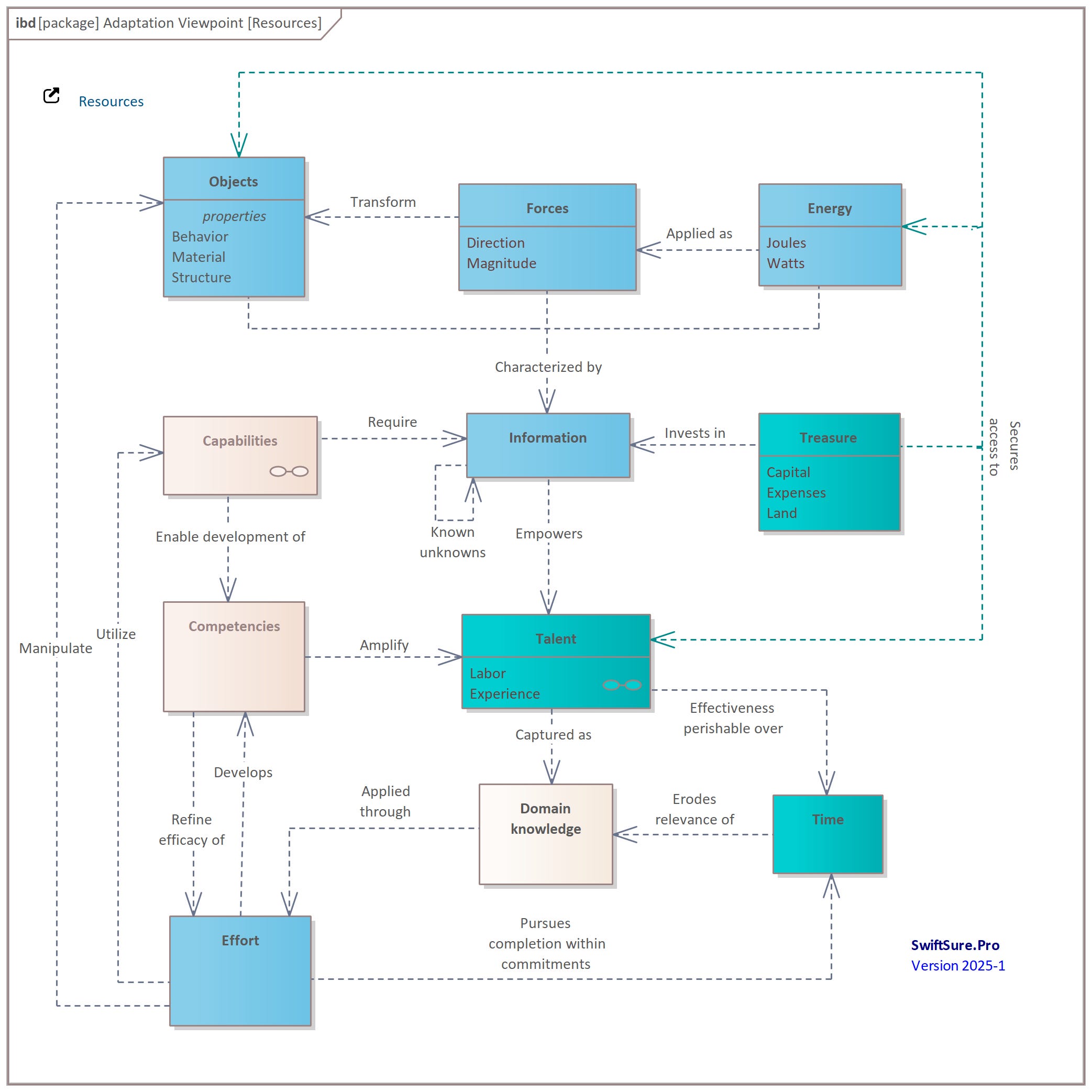

The concept of the means of production, depicted here in Figure 1, is widely used to signify the relationship between things used as inputs to a production system and the constituent mechanisms needed to provide those inputs - factories, tooling, systems, services, and methods - whether in a system of interest, or within an economy or society.

Karl Marx focused on these means of production to distinguish them from contributions by labor. Elon Musk sees them as levers for exponential innovation and automation. Two components of these means - resources and capabilities - deserve further detailing. For orientation for my intended use of the term power, see here.

Resources as power

Production for a system of interest consumes resources provided by upstream providers (who produce them) and produces resources for downstream consumers (who consume them). Energy is one of the most critical resources - the capacity to do work - since it fuels all actions, from powering a data center, lifting an object, or running a machine.

Energy comes in various forms - kinetic, potential, thermal, electrical, etc. Power is the rate at which these forces can be applied in accomplishing work or transferring resources. Think of it as the speed of doing work. It can tell us how effectively resources are being used to accomplish useful work. Energy is a stock, while power is a flow. If unfamiliar with this terminology, see this post.

The three primary resources, as shown in Figure 2, are time, talent, and treasure (capital), as those allow effort to be applied, capabilities to be matured, and objects to be transformed. While the selection of the other resources - forces, information, and raw materials - are important for efficiency, the primary forces enable better objects to be used in assembly, greater competency to be incorporated into capabilities, and better domain knowledge to be leveraged in performing the work.

Capabilities as power

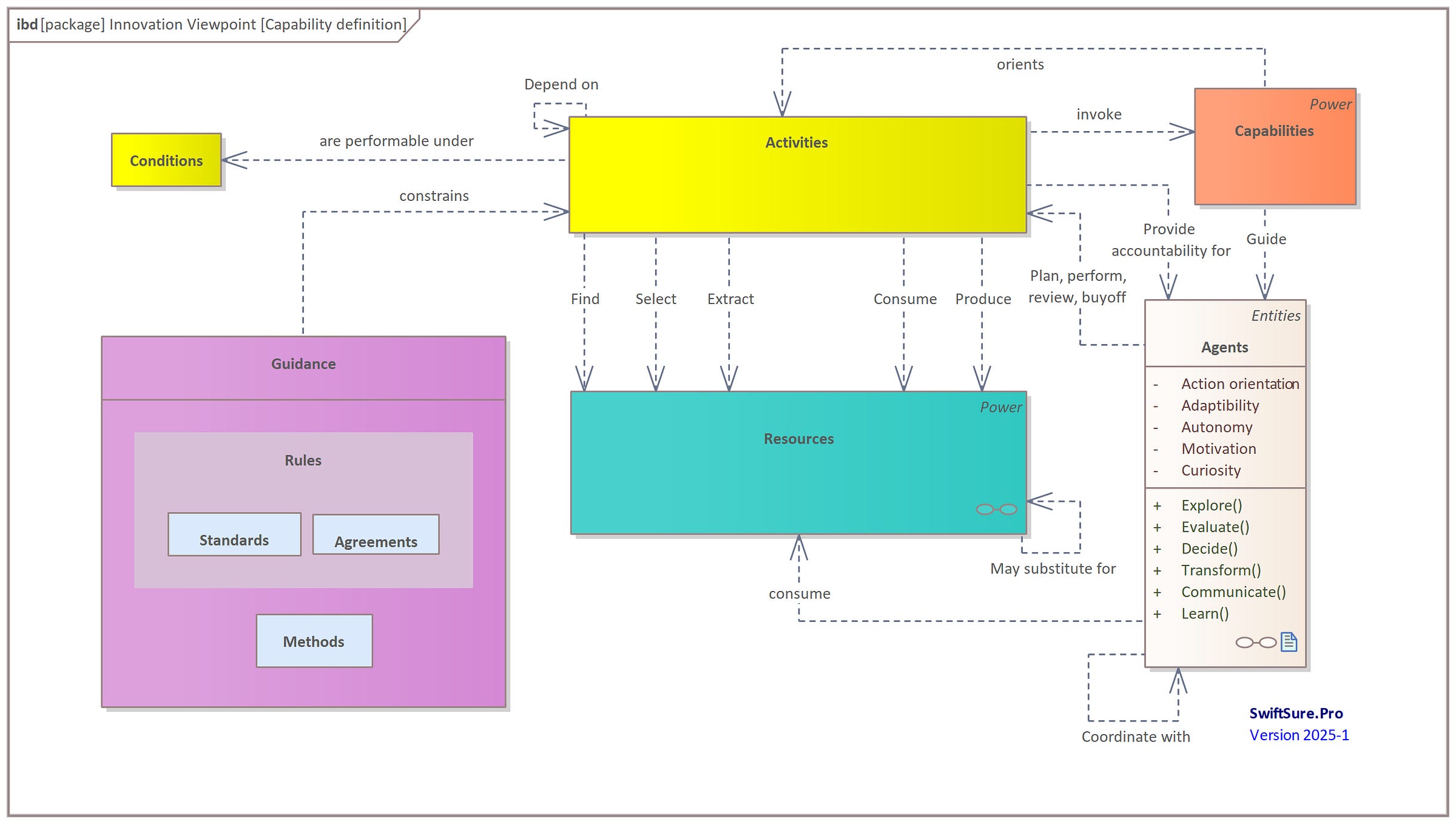

Capabilities (Figure 3) provide the ability to execute specified courses of action, and guide and constrain agents in performing these activities.

The concepts underpinning capabilities have had the greatest reach in military applications today, reflecting how armed forces think about applying power in conflicts while keeping a mission focus. The applications of these concepts focus on preparation - to understand how well forces can reliably employ resources within anticipated situations. This focus goes beyond traditional planning, which focuses on raw numbers of resources and equipment, to consider the capacity to successfully achieve desired courses of action. When considered in this context, capabilities are sources of power, but unlike resources, are not consumed in usage (though they can be degraded with time).

Maladies in production

Many things inevitably go wrong in accomplishing this work, especially when affected by complexity, external influences, resource shortages, quality breakdowns, and garbled communications. In this post we are focusing on the implicit structure for each production operation when encountering these situations. These are only apparent when observing patterns of operations across the requisite variety of contexts. When they arise, they lead to internal pivots in straightforward processing, or off-ramps from further processing. Such maladies are chronic, problematic conditions that introduce disruptions in production equilibrium, whether biological, psychological, or systemic. They often signal:

A misalignment between internal states and external demands

Flaws in communications and exchanges

Breakdowns in incorporating information from feedback loops

An inability to effectively adjust resource allocations as adverse conditions arise

Let’s examine the many types of pitfalls that are at the root of these production maladies:

Shortfalls or incorrect resources (time, talent, treasure, information) provided for the work

Breakdowns in preparation (orientation, architecture, stakeholder engagement) or orchestration of required actions

Inadequate attention to risks or change management

Slips and lapses in performing the work (resulting in defects that require rework)

Mistakes in analyzing what is needed for the work to be performed effectively

Performing work out of sequence

Mistakes in performing the work itself

Failure to properly document the work

Externalities adversely injecting change into endeavor

Improper use of tools - including automation - to situation

Incomplete testing of functions, performance, structures, or failure modes

Procedural disconnects (mismatches between situations and domain knowledge)

Each of these maladies threatens the orderly flow of work and thus adversely impacts throughput across each step of production.

The Minimum Viable Production Flow

If we are going to orchestrate production adequately, we must account for all these steps and transformations that occur, track the frequency, pace, and rework of each step, and use that information to learn to apply and mature capabilities and means of production to minimize non-value-added detours through this flow. The underlying steps and feedback loops are depicted in a stock and flow model, in which flows are represented by valve symbols representing transfer functions and stocks are represented as boxes depicting reservoirs. The processing steps are described generically here but are mappable to most situations. Note that inputs and outputs required by each step are not shown here but are implied in separate writings about portfolio management.

Once jobs are committed, the work is distributed across performing agents, depicted in Figure 6 as multiple parallel efforts for each step (when steps indicate depth):

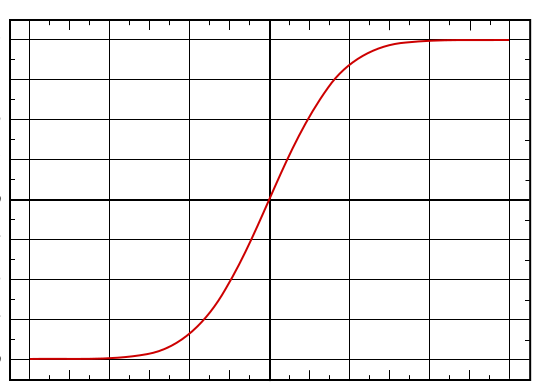

We want our model of these dynamics to be viable for representing as many situations as possible, while being as simple as possible. Performance of production systems is non-linear and classically follows what is described as an S-curve - the sigmoid function whose graph is shown in Figure 7. This pattern is consistent with the elements described in figure 3 of this post.

In Brian Potter’s book The Origins of Efficiency, these dynamics are described as follows:

When we talk about production methods, we’re really talking about technologies… a production process can be thought of as a large collection of different technologies strung together to accomplish a particular goal… For individual technologies, progress tends to follow an S-shaped curve, with time or effort on the horizontal axis and technological performance on the vertical axis.

Early on, the technology performs extremely poorly, if it works at all. The phenomenon at play in the technology may have only recently been discovered and as a result is poorly understood. It might not yet be clear how it behaves under different conditions, or what arrangement of components can best take advantage of it, or even for what purposes it might be harnessed. Fixing one problem with a nascent technology tends to simply reveal more problems, so significant time and effort might be invested without any noticeable increase in performance.

But over time, as scientists, engineers, and tinkerers explore different ways of implementing it, the technology’s characteristics become better understood. As people begin to figure out what works and what doesn’t, the search space of the technology is narrowed, and it attracts more talent and funding. As attention converges on the most promising avenues for advancement, performance improves more quickly… This gradual refinement that leaves the basic nature of the technology unchanged is often called incremental or evolutionary improvement. During this period, the technology might converge on a dominant design: a specific way of implementing the technology that can be easily adapted to serve the needs of many potential users.

Eventually, a technology’s performance approaches some natural limit: the maximum level of performance that the given effect or principle at work or the structure of the dominant design can achieve. As the technology approaches this limit, gains in performance are harder and harder to achieve, and the rate of improvement slows.

As the legend in Figure 6 indicates, the steps in our production process manifest performance through four phases (estimates below are approximations for a typical small to medium-sized endeavor):

Inception: the scope, goals, expected benefits, risks, and feasibility of the endeavor is assessed. The effort (~5%) and schedule (~10%) at this point are small but establish the baseline for future acceleration.

Elaboration: The requirements, strategy, and structure of the work are explored, and the necessary details are captured, organized into jobs ready for assignment, and baselined. The curve begins to steepen as more resources are engaged, and the definition of jobs and methods stabilizes. This phase involves ~20% of the overall effort and ~30% of the schedule.

Construction: As jobs are committed and prepared, actionable elements of the work elements are initiated, work in process is generated, results of that work are stabilized, and solution elements are aligned, with a focus on functionality and performance. This represents the bulk of cost (~65%) and schedule (~50%) consumption, powered by peak learning and velocity.

Transition: The solution is validated and made available for delivery, with training, validation, and final adjustments. Effort (~10%) flattens and schedule (~10%) reflects wrap-up activities.

The pathway through this landscape is challenging. Each step’s performance has a probability distribution reflecting the natural variation of processing. This variation is amplified as this variation, and its corresponding limits of capacity, inject uncertainty, incorporate feedback from downstream steps, as these functions interact, and adjust to maladies encountered along the way, rinsing, and repeating with each time increment.

Transfer functions

Transfer functions characterize each action’s output for each input. There will be many complex inputs in addition to what is shown in Figure 6; those collectively influence decisions that are abstracted into the Power value that feeds the rates of each step in the flow. Such functions can be implemented by human agents or agentic transformers.

The steps depicted in Figure 6 are outlined below, with flows (the transfer functions) stylized in bold, stocks in italics, and the transition indicated by an arrow character in the following lists. The normal flow (aka “happy path”) is described in the outermost, numbered outline level. These steps typically have one or more feedback loops that are captured underneath each step as indented, exception processing pathways which inject rework into its upstream steps, resulting in delays.

Step sequences

Observation: Signals → Opportunities

Observation is the act of noticing, watching, or measuring something to gather information. These observations can be passive or active; each involves:

Perception: Detecting the signals through sensing and communications

Attention: Focusing on specific signals while filtering out noise

Interpretation: Deriving meaning from perception free of influence from prior knowledge or bias

Signals come in many flavors - orders, resource shifts, support obligations, and expedite requests among them - but each requires ingredients in amounts appropriate to each situation. Noise can obfuscate these signals; indeed, when the level of noise exceeds the signal, chaos dominates the search for worthwhile opportunities, and can increase the likelihood of subsequent pivots, or influence decisions about needing to ignore opportunities. Incentives must be sufficient to amplify effort sufficiently to effectively capture the opportunities despite the noise.

Orientation: Opportunities → Goals

Goals are a bridge between intentions and execution. Orientation must validate the feasibility of each opportunity (considering timing, constraints, and achievable throughput), confirm relevance with priorities and values, and translate visions into outcomes that realize the intended successes. Goals should follow best practices and describe what success looks like in unambiguous terms, anchoring opportunities with timing to reinforce urgency, provide room for course corrections, and enable evolution as feedback reveals new insights or conditions.

Ignoring Opportunities

Not all opportunities are deemed worthwhile to pursue, so some number will out of necessity be ignored. Delays in processing are an indicator that such disposition should be considered.

Analysis: Goals → Requirements

Goals are analyzed and translated into requirements through the capture, refinement, and elaboration of context, intentions, and constraints into specific, testable conditions that must be satisfied.

Pivoting towards different Opportunities

Some goals are worthwhile in pursuing an opportunity but require revision prior to analysis.

Discarding Goals

Other goals are not critical to pursuing the opportunity and can be discarded.

Organization: Requirements → Jobs

In his book Competing against Luck, Clayton Christensen describes jobs from a customer’s perspective; progress involves understanding what that customer is trying to do in particular circumstances, and what decisions they must make. This step elaborates statements of work, allocates responsibilities, and distributes requirements across jobs for responsible agents.

Revisiting Requirements with respect to Goals

As requirements are fully considered, the need for clarification, conflict resolution, and addressing missing elements arises, forcing further work on the related requirements.

Commitment: Jobs → Preparation

Commitments require a psychological and relational progression through

three phases:

Understanding: Gaining clarity about the context and expectations for the jobs

Acceptance: Acknowledging and embracing the reality of these inputs and their relationship to the jobs being assigned (including responsibilities, relationships, limitations, and challenges)

Support: Agreeing to accept these responsibilities and collaborate upstream and downstream to ensure adequate progress is achieved

Preparation ensures actions connect to broader goals or narratives and empowers responsible agents to navigate this progression so that work can proceed in a straightforward fashion. This preparation is the traditional role that planning performs and enables parallel action in subsequent steps if sufficient agents and resources are available.

Refactoring Jobs given new Requirements

Requirements changes can necessitate adjustments to job structure considering those changes.

Provisioning: Preparation → Actionable work

Once the parties responsible have committed to perform the necessary work, preparation is performed to define the steps necessary, required interdependencies, and secure the resources necessary for implementing these steps. Work becomes actionable by provisioning the inputs necessary for execution.

Enhancing Preparation given new Jobs

Initiation: Actionable work → Work in process

Although work may be actionable, many factors can delay launching the effort:

Cognitive friction: Complexity can overwhelm; goals and requirements can lack clear definition; and uncertainty around prioritization and sequencing can paralyze action.

Emotional and relational factors: Anxiety, low motivation or energy, and insufficient alignment on values can burden progress with negotiation or avoidance.

Structural barriers: Poor integration of tools, unclear feedback mechanisms, multitasking, and resource shortages (promised but unfulfilled) can erode progress.

To optimize flow, these constraints should be addressed rather than passed downstream. Initiating action converts potential into momentum, shifting from planning to doing.

Augmenting Requirements after consideration of Actionable work

Revisions to requirements are typically triggered by new insights into stakeholder needs, technical feasibility, risk exposure, or strategic alignment. These insights often emerge from real-world feedback, evolving conditions, or deeper understanding gained in implementing these requirements.

Generation: Work in Process → Results

Each action is primed by clear intentions and requirements which set the direction and define what success looks like. Interactions with other actions and related systems feed checkout, incorporate feedback, and enable progress to be accumulated.

Discovering new Requirements while performing Work in Process

See 7.a

Inspection: Work in Process → Reviews

Reviews are a mechanism to generate signals that inform whether to continue, refine, or pivot work in process and candidate solutions. The entry conditions for such reviews are an important consideration in organizing the work.

Abandoning Work in Process

Effort invested in preparing for and performing work accumulates; when work is abandoned, those efforts are wasted and contribute to the opportunity costs of the endeavor.

Incorporation: Review results into Work in Process

Typical dispositions of review findings include acceptance, conditional acceptance, revision requests, rejection, and escalation for further action. These outcomes vary depending on the context - legal, academic, regulatory, or organizational - but they reflect the reviewer’s judgment on the adequacy, accuracy, and implications of the material reviewed. Additional actions required to achieve this disposition are added to the work in process.

Stabilization: Results → Solution elements

Elaboration, trial, and error powers the maturation of results into candidate solution elements.

Correcting Results

When results require correction relative to

Alignment: Solution elements → Candidate solutions

Holistic solutions require that the pieces interact properly and collectively satisfy requirements.

Diagnosing problems with Solution elements

Validation: Candidate solutions → Progress

Each proposed solution must be evaluated against real-world conditions before being released into service.

Isolating problems with Candidate Solutions through Reviews

The gears driving production rates

As Figure 6’s legend indicates, each step can be characterized into one of three categories, using the metaphor of a funnel:

Exploration: High Variability, Low Throughput

In exploration, we are in the wide part of the funnel - the scope of searches is wide, and the entropy is high.

Characteristics

Purpose: Discover options, surface unknowns, generate hypotheses

Inputs: Often ambiguous or incomplete

Outputs: Possibilities, insights, candidate pathways

Throughput Implications

Rate: Low and uneven; progress is nonlinear and often recursive

Variation: High given the low quality of information available; cognitive load, novelty, and branching paths reinforce this unpredictability

Constraints: Bottlenecks often stem from lack of clarity, insufficient framing, or premature convergence.

Evaluation: Moderate variability and throughput

Evaluations narrow the funnel through the incorporation of structured filtering.

Characteristics

Purpose: Compare, prioritize, validate, and assess trade-offs

Inputs: Structured options or hypotheses

Outputs: Ranked choices, decisions, or filtered paths

Throughput Implications

Rate: Moderate. Can accelerate with clear criteria and decision matrices.

Variation: Medium; depends on complexity of criteria and stakeholder alignment

Constraints: Bottlenecks arise from unclear metrics, cognitive bias, or decision fatigue

Transformation: Low Variability, High Throughput

These steps exploit upstream processing by operating as the nozzle of a funnel does, allowing agents to ‘turn the crank’ and deliver at high rates.

Characteristics

Purpose: Execute, build, incorporate, implement, or convert

Inputs: Validated decisions or designs

Outputs: Tangible results suitable for follow-on steps

Throughput Implications

Rate: High. Execution benefits from repeatability and automation

Variation: Low; standardized inputs yield predictable outputs

Constraints: Bottlenecks shift to resource availability, tooling, or integration points

Each exception processing step in the step sequences above are explorations for context by searching for the relevant details of the presenting conditions so the underlying problem can be accurately diagnosed. Transformations and evaluations have their own puzzles to be solved, but the context in both those cases is known - to produce a useful result within the attack surface of the territory and goal in question.

Wrap-up

Now that you understand this DNA of production generically, it should become apparent that even straightforward pathways can quickly become quite complicated. Such complications can be difficult to unwind, especially for the inexperienced. Practice and learning are the best medicine for such dilemmas. Such learning requires understanding each of the writings in this series, animating the above dynamics under alternative initial conditions and injections by externalities, and rehearsing the actions expected by each of the