Effective interactions among team members are critical in most endeavors. To examine how perturbations in such interactions can cascade across team members, I will adopt a metaphor of a simple mechanical device to represent the information flow across a system. The device we chose for this metaphor is quite primitive yet will prove useful to visualize how such interactions can unfold.

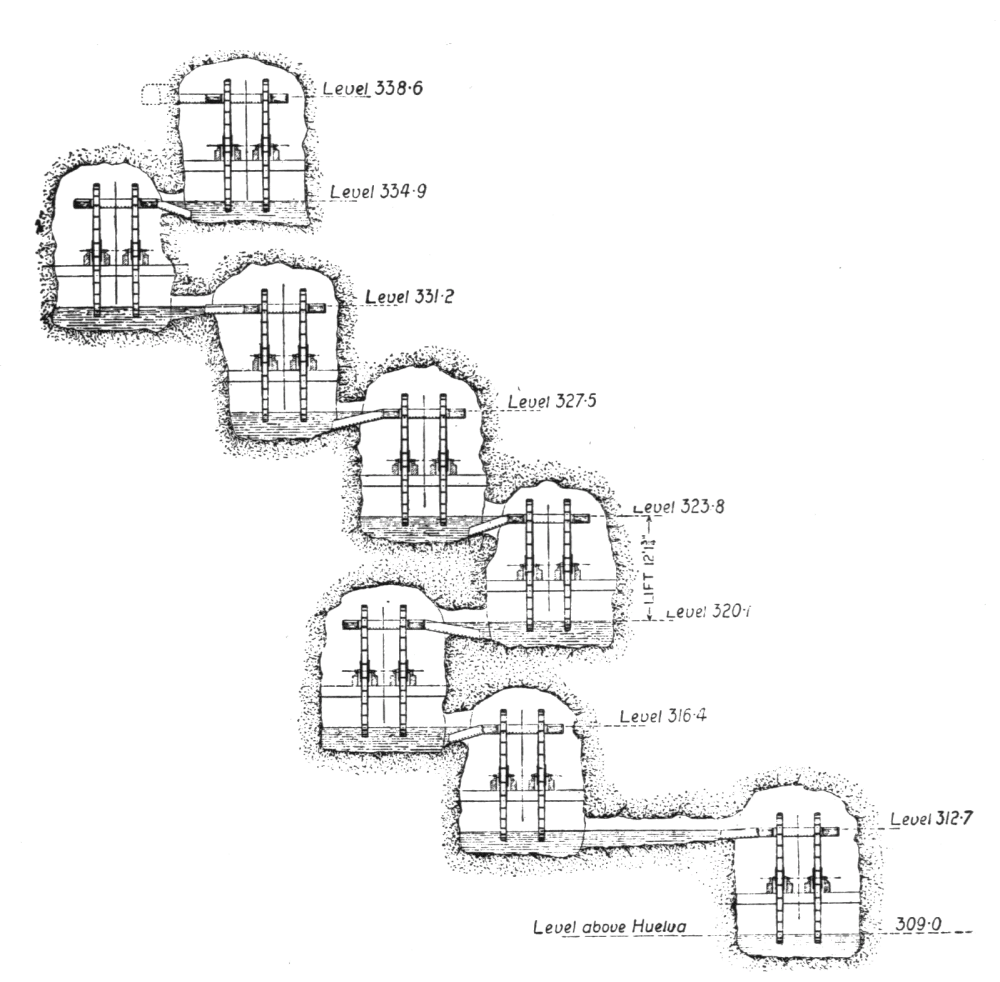

Figure 1 is a depiction of a real machine which was used around 60 A.D. for removing standing water from underground mines. These machines are known as reverse overshot water-wheels, and one of them was recovered from a copper mine at Rio Tinto in Spain and is now at the British Museum.

We know about these devices from the writings of Vitruvius, the Roman architect. He described a specific installation consisting of thirty-two water wheels, mounted and stacked above one another within the vertical shaft of a Roman mine. Each wheel was turned by one or more individuals who walked along the top of the water wheel to spin them.

A batch of water was raised up a specified distance as each worker turned their assigned wheel. This water then became a queue of work for the next higher wheel and worker to process. Each worker could only consume the output of the prior worker after enough water had accumulated at their assigned stage.

The pace of the slowest worker in the chain would thus constrain the end-to-end throughput potential across the entire device. Despite this limitation, their efforts were collectively able to lift the underground water about 200 vertical feet from the mines where they were installed, which was an impressive accomplishment for that time, and which gave the endeavors who used this technology advantage over other competing approaches, such as a bucket brigade.

This device can be considered from two distinctive perspectives. The first viewpoint consists of its capability to raise a column of water by a particular distance; we'll call this a water elevation system. The second perspective uses such a capability in the context of a larger ore extraction system; its primary goal is to economically produce ore which can then be provided as a resource for many other purposes that are not relevant to our example. The extraction of ore was financed by investors who saw this potential. Not all mines had water draining into the tunnels being mined, but when it did, the water represented a constraint which blocked the potential realization of value that could be achieved.

The economics of such ore extraction is determined by the value that ore has in the marketplace, the number of resources necessary to produce that ore, and how long it takes to produce it. Each mine would have unique characteristics, such as the volume of water flowing into the mine, and the height to which the water needed to be raised. The operation of an ore extraction system is only economically viable within a performance envelope and operating context which each device was designed to serve. The throughput of the water extraction system had to be sufficient to consume inflows from all sources of water and any accumulated pool of water present at startup.

The ore extraction system and the water elevation system are interdependent since each requires the other to provide value. The costs to develop and operate the water elevation system will be bounded by the economics of the ore and its transport to a location where the ore is used as an input to another system that would consume the ore, such as a smelter.

The water elevation system would require water to be drained sufficiently so that ore could be extracted from the mine. One can envision water seeping into these underground mines from many sources, such as from rainfall, springs, or underground streams. Each of these inflows may have a varying rate over time, such as when a sudden rainstorm occurred. It might not take many people to extract water during a dry period, and it might take a long time after a rainy period to remove sufficient water for the ore extraction to be resumed. Delays in developing or operating the water elevation system could lead to delays in the time it takes to perform ore extraction, and thus significantly reduce the time-adjusted value of that ore. The actions and skills required to produce operational outputs are fundamentally different from those necessary to develop new capabilities that could extract water more efficiently and effectively.

In this example, the ore is an output of a value chain. The water wheels which were used to raise water required personnel, equipment, information, and tools to realize the needed capability. The capability of a water wheel to remove this water would be determined by many factors, including the volume of water which each wheel could consume, the pace at which workers could operate the system, and the leakage which occurs across the elements of the system itself. During operation, pools of water formed at the boundaries between each processing stage performed by each wheel. The size of these pools can provide a visual indicator of the backlog of the work cells that are accomplishing that work. Such queues are inevitable in any development or production process, due to variation in the quality of requirements, the capacity of team members, and the information available to the team.

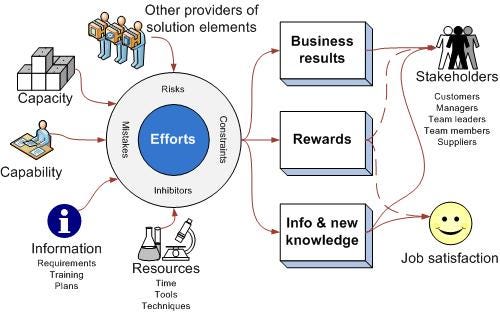

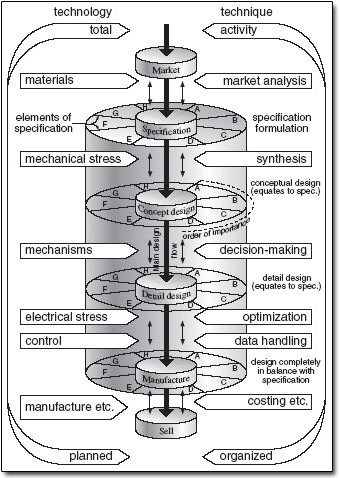

Development environments share most of the features of the water elevation system described above. In development settings, a cascading process is typically used, as depicted in Stuart Pugh's core design activity model of the interactions of technologies and technique shown in figure 2; note that in this case, the vertical flow is depicted top to bottom, unlike in the water wheels, which are subject to gravity. Each stage requires horizontal integration of the elements relevant to the structure of activities and material relevant to that stage, though the translation into wedges of activity depicted may vary by stage. The flow among team members involved in such designs can be thought of as similar to those of our cascading water elevation system.

The overall throughput of a team is a function of the interactions between the team members. Feedback can be used to manage the rates of injecting work (be it new or rework) into the system. The queues of work in process between team members can be used to provide visual indicators of the flow of this work as it moves through the system. The size of these queues will be dependent upon whether a batch production, job production, or continuous production technique is being used. A description of managing such flow is here.

Production decisions regarding the allocation of resources across work stages are often driven by the robustness of the forecasting information available, the cycle time variation inherent in each operation, and the quantity necessary for efficient economic operations.

The size of each batch to be processed across each stage of such an operation is critical for many reasons:

Communications costs grow as connections are n**n for n units, and many interactions are often necessary to coordinate the work across these channels

Large batch sizes limit efficiencies that may be achieved by performing similar and routine operations together

Large batch sizes also reduce the usefulness and effectiveness of feedback to improve the system, which complicates connecting cause and effect when something goes wrong.

The value of a batch of work can only be evaluated within the context of the environment within which that work is being performed. A tool (like the water wheels used to provide the capability to elevate the water in question) is only a means to an end; in the case of mining, the immediate mission is to extract marketable ore from geological deposits. Far too often, we are inclined to measure value by quantifying the resources which are visible, or which are easy to measure, rather than by the flow of this work in the context in which value is realized. This can cause us to measure work by the number of people who decend into the mines each day, rather than considering the efficiencies actually being realized in the various stages of the flow. As Donald Reinertsen indicates:

Product developers create a large number of proxy objectives: increase innovation, improve quality, conform to plan, shorten development cycles, eliminate waste, etc. Unfortunately, they rarely understand how these proxy objectives quantitatively influence profits. Without this quantitative mapping, they cannot evaluate decisions that affect multiple interacting objectives...

Life would be quite simple if only one thing changed at a time. We could ask easy questions like, "Who wants to eliminate waste?" and everyone would answer, "Me!" However, real-world decisions almost never affect only a single proxy variable. In reality, we must assess how much time and effort we are willing to trade for eliminating a specific amount of waste.

A modern, kid-powered version of one stage of this water wheel is in use today for pumping water in under-developed countries. In field use, such devices have failed to meet expectations, and have proved to be more costly, less reliable, and harder to use than the child's play they were likely marketed to be. Regardless of the outcomes expected from such production systems - be they technology maturity, new product development, or service excellence - value can only be realized once solutions have been completed and have been placed into service. This can only occur at the rate of acceptance of the methods by users and the throughput of the system overall.

Until then, investments are just holding costs for an uncertain future. They merely represent an inventory of work which has begun but which has not yet been completed. This inventory can be particularly large for software-intensive efforts since the inventory is less tangible than it is for physical assets. This means that investments in labor may exceed the costs of materials, especially when the costs of paying for this labor pool over time are made visible. The size of this inventory is equally critical, since the value they offer may become stale over time, as opportunities for usage and customer enthusiasm for requested work tend to evaporate during dry seasons.