Aligning behaviors and intentions

What one does is what counts. Not what one had the intention of doing. – Pablo Picasso

Longevity in business isn’t earned by simply preserving core ideals—it demands a tension between intention and reinvention. As market realities shift, behaviors must evolve to remain coherent and effective. This is the paradox many firms face: honoring what made them successful while questioning whether those same behaviors serve tomorrow’s context.

In 1997, James Collins wrote Built to Last, which went on to become an immediate classic on corporate strategy. It focused on eighteen noteworthy companies (all within the United States) that had each survived for over one hundred years at the time of the book's publication. When Built to Last was published in 1997, it promised strategic permanence through shared corporate behaviors. But by 2007, half of its exemplary companies had faded from prominence. The prescription, while well-meaning, now reads more like cargo cult programming, imitating past success without adapting to future demands.

The need for adaptation

Long-lived businesses don’t simply endure—they continuously redefine themselves. Failing to adapt erodes focus and responsiveness, trapping organizations in past successes that no longer apply. This erosion crosses sectors, affecting entrepreneurial ventures, industrial giants, and public institutions alike.

Consider Microsoft and Kodak between 1985 and 2005: both faced digitalization, globalization, and the collapse of legacy channels. One recalibrated, the other clung to its film roots. The divergence underscores that survival favors those who evolve, not those who presume past relevance guarantees future viability.

It’s understandable for successful organizations to resist change—especially when prior methods delivered results. Yet the conditions that made those strategies effective may no longer exist. Change demands not just recognition, but intentional resource allocation and sustained focus. Meanwhile, legacy operations continue demanding attention, often crowding out the capacity for renewal.

Shared principles of successful companies

I am lucky enough to work in the Puget Sound area, which is home to four premier companies in their respective industries. Surveying the principles of these companies, one is struck by how similar their intentions are:

Customer-Centricity

Boeing: Commitment to safety, quality, and reliability in aerospace products.

Microsoft: Innovation and collaboration to deliver value to users.

Costco: Building customer loyalty through consistent value and service.

Amazon: Customer obsession, starting with the customer and working backward.

Operational Excellence

Boeing: Strong focus on compliance, ethics, and environmental responsibility.

Microsoft: Driving clarity, energy, and success through leadership.

Costco: High sales volume and low margins for operational efficiency.

Amazon: Ambitious standards and ownership to ensure excellent outcomes.

Innovation and Growth

Boeing: Aerospace innovation to connect, protect, and inspire the world.

Microsoft: Fostering a growth mindset and encouraging adaptability.

Costco: Using a membership-based model to drive consistent growth.

Amazon: Encouraging invention and simplifying processes.

Employee Focus

Boeing: Commitment to employee safety and ethical working conditions.

Microsoft: Prioritizing employee well-being and development.

Costco: Competitive wages, benefits, and internal promotions.

Amazon: Ownership mentality and promoting ambitious standards.

Sustainability and Long-Term Thinking

Boeing: Environmental stewardship and values-driven governance.

Microsoft: Strategic partnerships for collaborative success.

Costco: Commitment to low prices over the long term.

Amazon: Prioritizing sustainable growth over short-term gains.

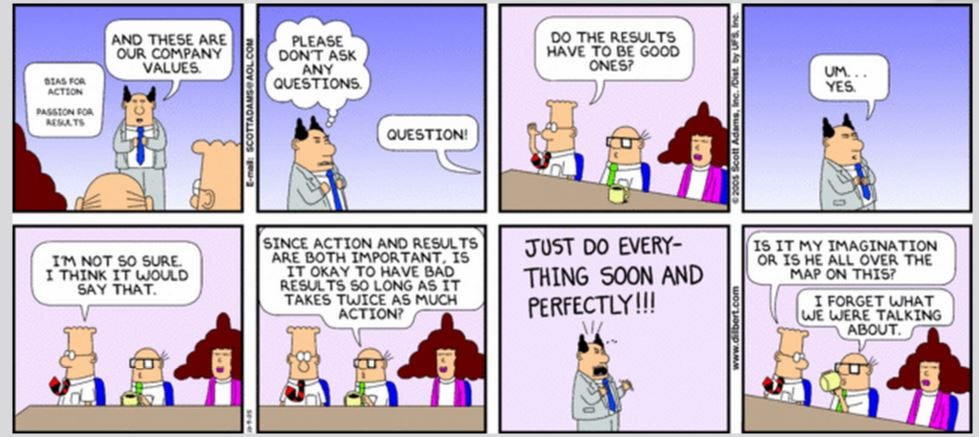

So how can such organizations effectively pursue such long-term intentions, while meeting demands imposed by short-term commitments?

The difficulty lies not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones. - John Maynard Keynes, 1935

Things do not become faster, better, or cheaper by osmosis, patience, or cheerleading, but by learning the basics of execution discipline. As Complein reminds us:

The organization of any major human endeavor follows basic laws of efficiency of communication, span of control, xenophobia, specialization, and other sociological forces that drive similar undertakings to implement similar practices and structures. Systems of nature have common rhythms and trends that underlie their emergent complexity. These properties come from the structure of their organization: the deeply held relationships that define the organization as a social entity.

Clarifying performance objectives

To demonstrate the challenge of balancing these needs, consider which goals deserve what emphasis among options for customer satisfaction, speed, agility, or discipline? The answer should be simple - speed is everything since it provides the key to unlock the other goals by facilitating more rapid learning. Yet while everyone may want to operate faster, speed doesn't just emerge from such desire, and speed without discipline just produces waste faster.

According to Donald Schon, the systemic changes required to improve performance will not necessarily be obvious from inside the organizational constructs that people perform their work within:

Russell Ackoff recently announced to his colleagues that "the future of operations research is past" because "managers are not confronted with problems that are independent of each other, but with dynamic situations that consist of complex systems of changing problems that interact with each other. I call such situations messes. Problems are abstractions extracted from messes by analysis; they are to messes as atoms are to tables and charts... managers do not solve problems: they manage messes".

Problems are interconnected, environments are turbulent, and the future is indeterminate just in so far as managers can shape it by their actions. What is called for, under these conditions, is... the active, synthetic skill of "designing a desirable future and inventing ways of bringing it about". Engineers encounter unique problems of design and are called upon to analyze failures of structures or materials under conditions which make it impossible to apply standard tests and measurements.

Practitioners are frequently embroiled in conflicts of values, goals, purposes, and interests. Each view of professional practice represents a way of functioning in situations of indeterminacy and value conflict, but the multiplicity of conflicting views poses a predicament for the practitioner who must choose among multiple approaches to practice or devise his own way of combining them.

To accelerate learning across this landscape is to embrace the transparency necessary to build trust and generate a business model that is explainable, realistic, and sustainable. Since any organizational structure or culture is resistant to change, elements of the existing structure must be dismantled, then re-formed to naturally flow from and work with (rather than against) Complein's laws. The newly formed units can then begin to align their investment strategies, organizational structures, and resource allocations with this business model across all levels of the organization.

Framing the target end states

The next step in successfully performing such pivots requires defining a clear, robust, and measurable set of goals that frame the target end state and characterize the new behaviors which must be in place to realize it. Mark Pincus, the co-founder of Zynga, has said that not having clear and actionable goals can lead to death by a thousand compromises. Goals should delineate real choices made by the organization and intended to be supported by their members, rather than just regurgitating nebulous slogans without elaboration.

As the scale and complexity of a business increases, the robustness of the activities 'on the ground' necessary for meaningful progress becomes increasingly critical. Realizing such goals over multiple business cycles requires interpreting them within the context in which they are to be applied and applying a foundational set of disciplines for such goals to be realized. Most organizations, unfortunately, focus instead on only the visible aspects of projects, such as appealing new features. This can distract them from considering the invisible aspects - like outdated architecture and technical debt - which can sap the energy from the team creating and supporting new features and make it harder to realize value for everyone.

The need for discipline

The word discipline is a synonym for many related concepts, including governance, best practices, and process improvement. Each of these interventions inevitably rests on the ability to introduce behavioral changes which will influence the way work is performed. These behaviors may need to be shaped at many distinct levels. Any large organization is likely to have evolved into a mix of many different work cultures; each may consider themselves disciplined within their local context. Economist Thomas Sowell identifies the crucial aspect of knowledge exchanges across these boundaries:

Economic transactions are purchases and sales of knowledge. Even the hiring of an "unskilled" worker to pump gas involves the purchase of a knowledge of the importance of dependability, punctuality, and an ability to get along with customers and co-workers, quite aside from the modest technological knowledge required to operate the gasoline pump. The abstract existence of knowledge means nothing unless it is applied at the point of decision and action.

More complex operations obviously involve more complex knowledge-often far more complex than any given individual can master. The person who can successfully man a gas pump or even manage a filling station probably knows little or nothing about the molecular chemistry of petroleum, and a molecular chemist is probably equally uninformed or misinformed as to the problems of finance, product mix, location, and other factors which determine the success or failure of a filling station, and both the manager and the chemist probably know virtually nothing about the geological principles which determine the best way and best places to explore for oil-or about the financial complexities of the speculative investments which pay for this costly and uncertain process.

We are all in the business of selling and buying knowledge from one another, because we are each so profoundly ignorant of what it takes to complete the whole process of which we are a part.

The foundational disciplines required for building products will vary significantly depending upon the nature of the product itself. For example, a chemical engineer, a building contractor, and a software designer must each have insights into the decisions and work products required within their specialization. Yet when a particular statement of work requires interdisciplinary cooperation, the potentially competing perspectives of their different disciplines must dive into details meaningful to specialists in limited supply, such as chemical bonds, material properties, and optimal algorithm selections. These individual pieces need to interact effectively to deliver the functionality and performance which is required overall.

Constructs for improvement

Several patterns are common to how resources can be employed to pursue enhanced performance. The most frequently used constructs within this environment are:

Process action teams, in which participants are expected to carve out time from their primary assignments to craft appropriate governance for the broader community; unfortunately, since participation is temporary, momentum is difficult to establish and sustain.

Functional organizations that are chartered to provide 'bench strength' when projects run into problems; unfortunately, if the bench is that good, they should be starters.

Communities of practice, which attempt to self-organize within their available bandwidth to promote whatever they see in their best self-interest. Their rallying cry is a demand for consensus so that they can block changes unfavorable to any part of the community

Designated approval authorities who are expected to assure desired outcomes, without the ability to themselves dictate the means to those ends

Dedicated subject matter experts who are positioned to? launch of new projects, to make sure they are on the right path

Consultants who have less invested in outcomes than those they advise

These interventions share similar challenges in changing existing cultures - how to transfer know-what and know-how to groups that are likely to view any imposed discipline as unnecessary, misguided, or irrelevant to their situations. These postures are unfortunately often adopted in response to some crisis, and with 20-20 hindsight may receive a mandate to address the immediate symptoms of the problem, rather than making a long-term commitment to curing their root causes. Most recruits into crisis management are fire-fighters; unfortunately, while they are in the middle of fighting one fire, more fires inevitably ignite and spread.

Visualizing the changes required

Here’s a three-step approach - grounded in project-management gap analysis and behavioral-science research and consistent with the PIANOS model - for both measuring and then visualizing the intention–action gap in live projects:

Quantify the Gap

Time-Lag Measurement:

• Timestamp every new intention (e.g. idea logged, meeting decision) and record when the first tangible action occurs. Over a cohort of intentions, you can calculate median, variance, and trends of “execution lag”.Completion-Rate Measurement:

• For each intention, track “acted-on” vs “abandoned.” The ratio (actions ÷ intentions) over a fixed window becomes your Action-Conversion Rate.Outcome-Metric Gap:

• Use classic gap-analysis by defining your desired performance measures (e.g. features delivered per release, compliance tasks closed), measure actual performance, and compute the delta.

Diagnose Root Causes

For each intention that stalls, evaluate whether the issue stems from lack of skill, will, or support using quick “post-mortem” surveys or team retrospectives. This lets you see which barrier most often derails execution. Target solutions - training, incentives, or structural changes - via intervention design.Visualize for Insight & Action

Delay Histogram or Box-Plot:

• Plot execution lag distribution to spot outliers and the “bulk” of your delays.Burn-Up Chart Overlay:

• On your endeavor’s burn-up chart, add a second line showing “intentions logged.” The vertical gap between lines at any date is your live intention–action backlog.Sankey Diagram:

• Map “intentions” flowing into three bands—acted on, flagged for K/M/O causes, or dropped—using width to show volume leak.Heatmap Matrix:

• Rows = by responsible unit; columns = gap type (time-lag, conversion-rate, KPI). Use color‐intensity to highlight worst offenders.Kanban-Style Cumulative Flow:

• Add an “Intention” column before “To-Do” and measure how long cards linger there. The thicker that column, the bigger your upstream gap.

Consider tying these visuals into your regular stand-ups or dashboards so the team constantly “sees” where intentions stall and can swarm to close those gaps.

Call to action

When combinations of these strategies are employed, many leaders (already challenged by limited attention spans to address another fire) delegate the coordination responsibilities necessary for meaningful changes to stick. Yet when the structure of the organization itself is problematic, such delegation may just add noise and obfuscate the underlying root causes and thus block change (while delaying their resolution). As Steve Jobs would say, such people need to think and act differently, not just talk and talk.

Organizations must regularly recalibrate what they do—not just what they say they intend to do. Success is sustained not by clinging to legacy, but by confronting the friction between mission and motion. It’s time to reexamine the story we tell ourselves and ask: are our behaviors aligned with what today demands?