Focusing attention on the most important details

This is the first article of a series on elaboration.

Throughout my career, I have observed that people are often attentive to and focused on distinct levels of refinement in discussions about concepts. Their perspectives seem to vary according to their roles on a project, their individual personalities, and their firsthand experiences in similar situations. I have come to mentally categorize these individuals into one of two different personality types that can be thought of as existing at the top and bottom of a granularity perception universe. I will describe these as "Roughly Right" people, and "Precisely Right" people.

When you are a Precisely Right person and are presenting a topic to an audience primarily composed of Roughly Right people, it is easy to spend most of your time covering a lot of details, since that is the way to naturally communicate ideas. Unfortunately, you are likely to lose the Roughly Right people in your audience as you go over these details or trigger an impatient demand from them to get to the point.

Yet the opposite situation is also true; when Roughly Right people are communicating with Precisely Right types, breakdowns can occur unless the Precisely Right people are provided with the details they crave, since otherwise they may not feel that they adequately understand high-level ideas or notional concepts. As these details emerge, the Roughly Right may then struggle in obtaining commitments from the Precisely Right, if these details require different pivots than expected.

To do great things, to really learn, you can’t shout suggestions from the rooftop then move on while someone else does the work. You have to get your hands dirty. You have to care about every step, lovingly craft every detail. You have to be there when it falls apart so you can put it back together. You have to actually do the job. You have to love the job. - Tony Fadell, Build

As John Sterman indicates in his book, Business Dynamics, the uncertainties and instability that results from ambiguous information sources must be reconciled for decision-making on projects to be effective:

Much of the information we receive is ambiguous. Ambiguity arises because changes in the state of the system resulting from our own decisions are confounded with simultaneous changes in a host of other variables. The number of variables that might affect the system vastly overwhelms the data available to rule out alternative theories and competing interpretations. This identification problem plagues both qualitative and quantitative approaches. In the qualitative realm, ambiguity arises form the ability of language to support multiple meanings… Rich, ambiguous texts, with multiple layers of meaning, often make for beautiful and profound art, along with employment for literary critics, but also make it hard to know the minds of others, rule out competing hypotheses, and evaluate the impact of our past actions so we can decide how to act in the future.

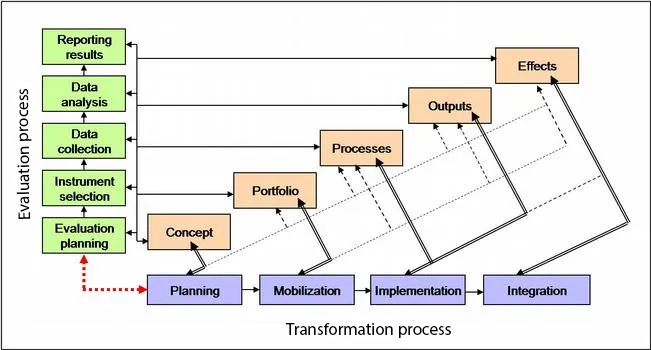

Successful projects must thus provide a reliable means of engaging with both Roughly Right and Precisely Right people. Leaders must achieve a collective buy-in from both types of people to resolve this ambiguity. Ideally, requirements provide an adequate foundation for shaping and evolving high-level concepts and incorporating necessary design details coherently and comprehensively. Translating and refining such information requires persistence, discipline, time, energy, resources, and sufficient attention for elaboration. Otherwise, the path to solutions may be dominated by change and rework as the project unfolds over time, resulting in projects which never seem to finish, and fail to meet expectations.

During the elaboration of these needed details, gaps of knowledge and interpretation will inevitably be discovered. Our ability to effectively engage subject matter experts to discover these details for each circumstance will be crucial to making sure these gaps are closed. This can challenge any team to achieve consistently. Until these details are revealed, the work necessary may not yet be actionable. One of the underlying causes for this lack of clarity is that it is easy for each of these types to assume that everyone shares the same cognitive framework, and that deriving an understanding and meaning from this framework should be straightforward and predictable. Too often, the work necessary to establish such a framework is often overlooked. As Fred Brooks describes it in The Design of Design:

As… complexity grows, the need for explicit use models increases. Even for a shovel, it is important to be explicit as to whether it is for coal, dirt, grain, snow, or some mix; whether for child, woman, or man; whether for the casual user or the manual laborer. How much greater is the need for explicit use models for a truck, a spreadsheet, an academic building! Moreover, the more complex the design, the less likely the designers are to be domain experts who could do the users’ jobs. Implicitly assumed models are then much more dangerous.

All designers in fact have user and use models consciously or subconsciously... as they work. Team design creates the all-new requirement that the entire team have the same user model, the same use model. This requires explicit models and assumptions. This exercise is rare because the members of the team usually believe, without anyone saying so, that they share a common set of assumptions. After all, each one heard the enterprise leader charge and challenge the team. Each one has read the goal-defining document. All are expert.

Matters are not so simple. Each of us has in fact had a different experience using similar systems; my experience informs my picture of the typical user. Each of us has been exposed to a different set of applications; my exposure helps me define this application. If the team does not draft a common set of explicit assumptions, each designer will work with a distinct set of implicit ones. Microdecisions too minor ever to be discussed will be made differently, and conceptual integrity will be lost.

Roughly Right people tend to be first movers and starters. From their frame of reference, they often lose interest in projects before the required details are defined. In contrast, Precisely Right people are often finishers, the unspoken heroes who must save projects that were built with good intentions but flawed assumptions. You can't expect Roughly Right people to be able to provide all the details that are needed by Precisely Right people. But until the individuals responsible that need this information have access to these details, you also can't expect teams of those people to have sufficient control over the factors critical to success. They will then fall back on satisfying what they had understood needs from one stakeholder's viewpoints, which may or may not satisfy things from the perspective of other stakeholders.

The way forward requires Roughly Right people to acknowledge there are such gaps, even though they rarely are the ones who will have the persistence or discipline to close them. Precisely Right people must learn to effectively communicate what kinds of gaps exist for a body of work to be actionable. Trust is built once everyone can agree that finding the way through such clouds of ambiguity is more like hacking through a jungle than like following a GPS-calibrated moving map to a destination. Environments are jungle-like when they require sifting through extensive information from many problem domains and elaborating work so that other individuals can take constructive courses of action, assure this work is being accomplished effectively, and validate that this work has sufficient value to be worthwhile.

Leaders (often roughly right people) must commit to projects before all these details are fully defined. Those responsible for deciphering and implementing their intentions (ideally, precisely right people) must assure that such commitments have access to sufficient contingent resources so these project commitments can be clearly defined and achieved, despite the uncertainties of direction from above. As a result, both types need each other, but must learn to work together effectively, given their shared destiny.