We who wrestle with systems

"We shape our buildings; thereafter, they shape us.” – Winston Churchill

Systems aren't abstract blueprints; they’re the scaffolding of our decisions, tensions, and compromises. From aircraft design to embedded software, from government to grassroots, we move through systems, and they move through us. This post is an exploration of how context refracts structure, how perspective warps intent, and how every so-called ‘system’ is as much a cultural artifact as it is a technical one. The question isn’t whether you're operating within a system. The question is: which part are you shaping - and which part is shaping you?

Throughout my professional career, I have encountered the term “system”, usually with a functional descriptor preceding it. In college, it was database systems, operating systems, etc. When I began working for Boeing, a new set of functional descriptors associated with the top-level airplane system itself were revealed, including avionics systems, flight controls systems, propulsion systems, electrical systems, and many others. I also learned about Conway’s Law, which was coined by the computer programmer Melvin Conway in 1967, which states:

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure.

This idea has profound implications. In systems development, it explains why modular teams produce modular components. In product design, it suggests that organizational silos can lead to fragmented user experiences. In systems thinking, it highlights how internal dynamics shape external outputs.

A definition

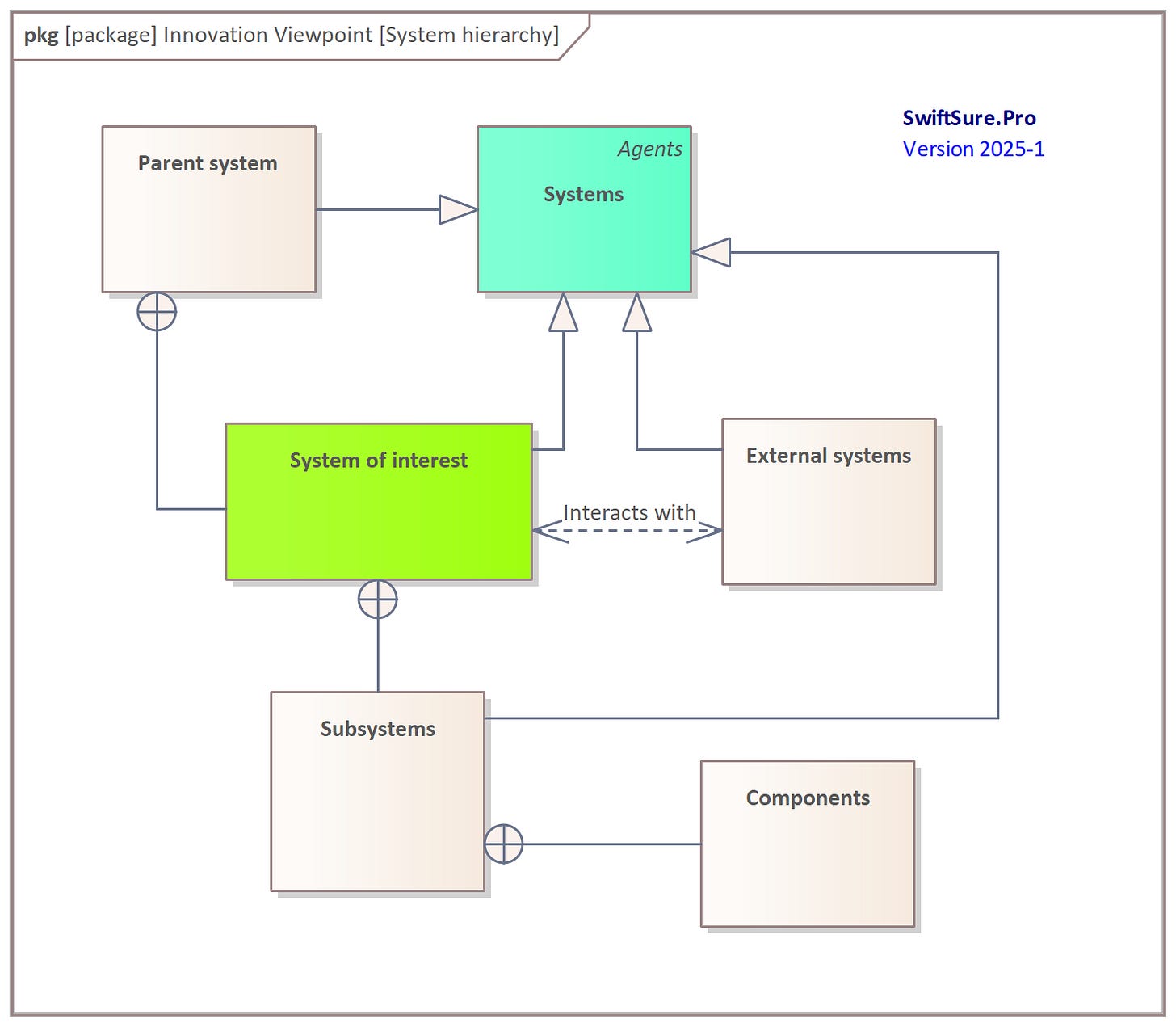

But what is a system? There are many definitions, so here is mine: A system is a set of parts that interact, manifest acceptable properties, and produce useful behaviors. The concept is recursive, at higher and lower levels (see Figure 1). For example, as humans, we operate on a platform of a metabolic system, that itself is made up of many cellular subsystems. We also operate within the context of an environmental system which itself exists within a planetary and solar system, and so forth.

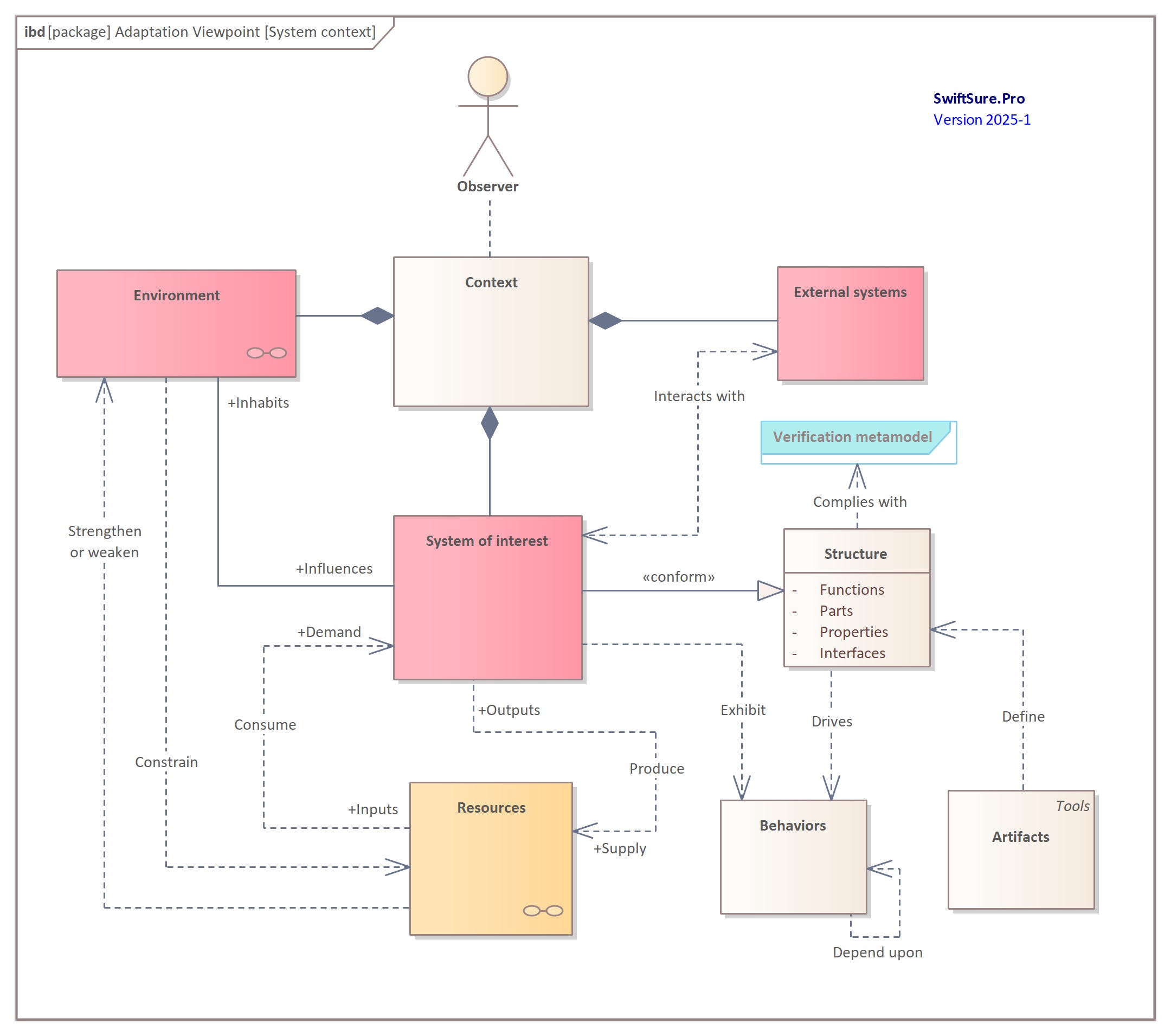

When studying the relationships between the periphery of any system and the rest of the system - whether a human cell, a complex device, or a social system - one realizes that there is no “center”. The context depends upon an observer’s frame of reference in which it operates (Figure 2).

There are many of these viewpoints for any system of interest, among them:

A strategic viewpoint, with the system as context, and the rules, constraints, and goals for how the system of interest, subsystems, and agents should work together

A design viewpoint, describing the system as it will be constructed (see Figure 3 below)

An operational viewpoint, with the system as mechanism, processing inputs and producing outputs. This view depicts how decisions, constraints, and interactions during operations shape outcomes.

A reflective viewpoint, with the system as a construct indicating how observers perceive the system, with mental models, biases, and assumptions.

Each of these viewpoints is influenced by feedback, which tracks what the system produces and compares it with what was intended. This feedback may also activate latent capabilities, prompt new configurations, and energize correction, adaptation, and innovation power requirements.

Applying a systems approach to system development

Erhard Reichlin, author of the Art of System Architecting, describes the application of a systems approach as:

... one that focuses on the system as a whole, linking value judgments (what is desired) and design decisions (what is feasible). A true systems approach means that the design process includes the problem as well as the solution. If a system is to succeed, it must satisfy a useful purpose at an affordable cost for an acceptable period of time.

Now consider the meaning of each of the italicized words in Reichlin's description. Such abstractions are sometimes utilized by evangelists advocating investments with roughly-right people, sometimes things are deliberately opaque for political purposes or to provide maneuvering room. Yet until such abstractions are sufficiently elaborated into clear, specific, and actionable requirements, any efforts to pursue these goals are likely to be less focused and can fall short of meeting the needs of all (or even the most important) stakeholders.

These forces operate within a system architecture with many interdependencies which must be unpacked, as represented in Figure 4.

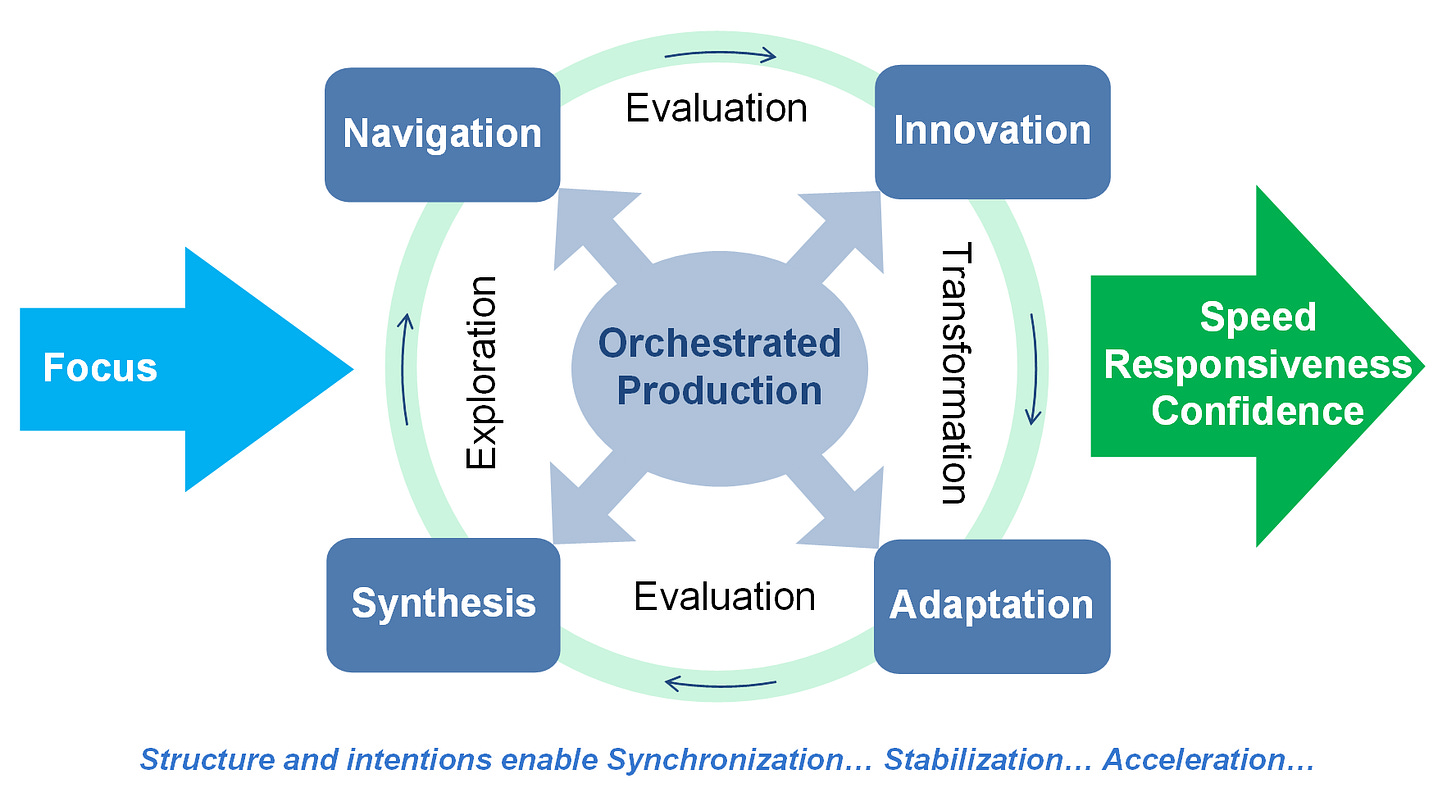

Unleashing the dynamics

Changes to a system of interest typically unfold in an iterative fashion under multiple forces exerted through the fields of the PIANOS model, summarized in Figure 5. Value can be created when changes to such systems through orchestrated production will address the needs of its stakeholders better than existing alternatives.

The call to action

When we treat systems as static, we miss the living, breathing interplay of innovation, adaptation, synthesis, and power. To wrestle with a system is to wrestle with ourselves. But to do so mindfully, by tracing the threads from intent to outcome and back again, is to craft better questions, clearer compasses, and braver choices.

If any of this resonates, the next step isn’t to add complexity. It’s to pause, reframe, and ask: what parts of your systems of interest are you affecting, how effective is that engagement, and what can be done to accelerate swift, confident, and sustainable production?