What's in a name?

The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao; the name that can be named is not the eternal name. - Laozi, Tao Te Ching

Names and descriptions are mere representations and cannot fully encapsulate the essence of things. But all things have names (including unnamed things we call things). The power to assign names is historic, and includes an obligation to assign its intended meaning:

Now the Lord God had formed out of the ground all the wild animals and all the birds in the sky. He brought them to the man to see what he would name them; and whatever the man called each living creature, that was its name. So the man gave names to all the livestock, the birds in the sky and all the wild animals. - Genesis 2:19–20

This passage is often interpreted as humanity’s first act of classification and stewardship, a symbolic gesture of understanding, responsibility, and creativity. It also highlights the relational dynamic between humans and the rest of creation: naming implies attentiveness and authority within a broader context. These ideas will be a recurring theme in my posts.

Classical thinking on names

Classical philosophers - especially Plato and Aristotle - had rich and contrasting views on the nature and function of names. Their debates laid the groundwork for centuries of thought on language, meaning, and reality.

In Plato’s Dialogs, he explores whether names are arbitrary labels agreed upon by social custom or instead are somehow intrinsically connected to the essence of what they name. Through his character Socrates, he leans toward the idea that a “correct” name reflects the true nature of a thing, arguing that names can be crafted to mirror the essence of their referents. But he also acknowledges the limits of this view, admitting that names are imperfect shadows of Forms (the true realities beyond language).

Aristotle takes a more pragmatic and systematic approach. For him, names are spoken sounds that have significance by convention, not by nature, signifying concepts or essences. For him, names are ways to classify and describe the fundamental units of reality. He invites us to seek deeper truths behind words and gives us tools to reason clearly with them.

Together, they frame a tension between essence and convention that animates philosophy, linguistics, and AI. Over time, such ideas crystallized into ontology, the philosophical study of being.

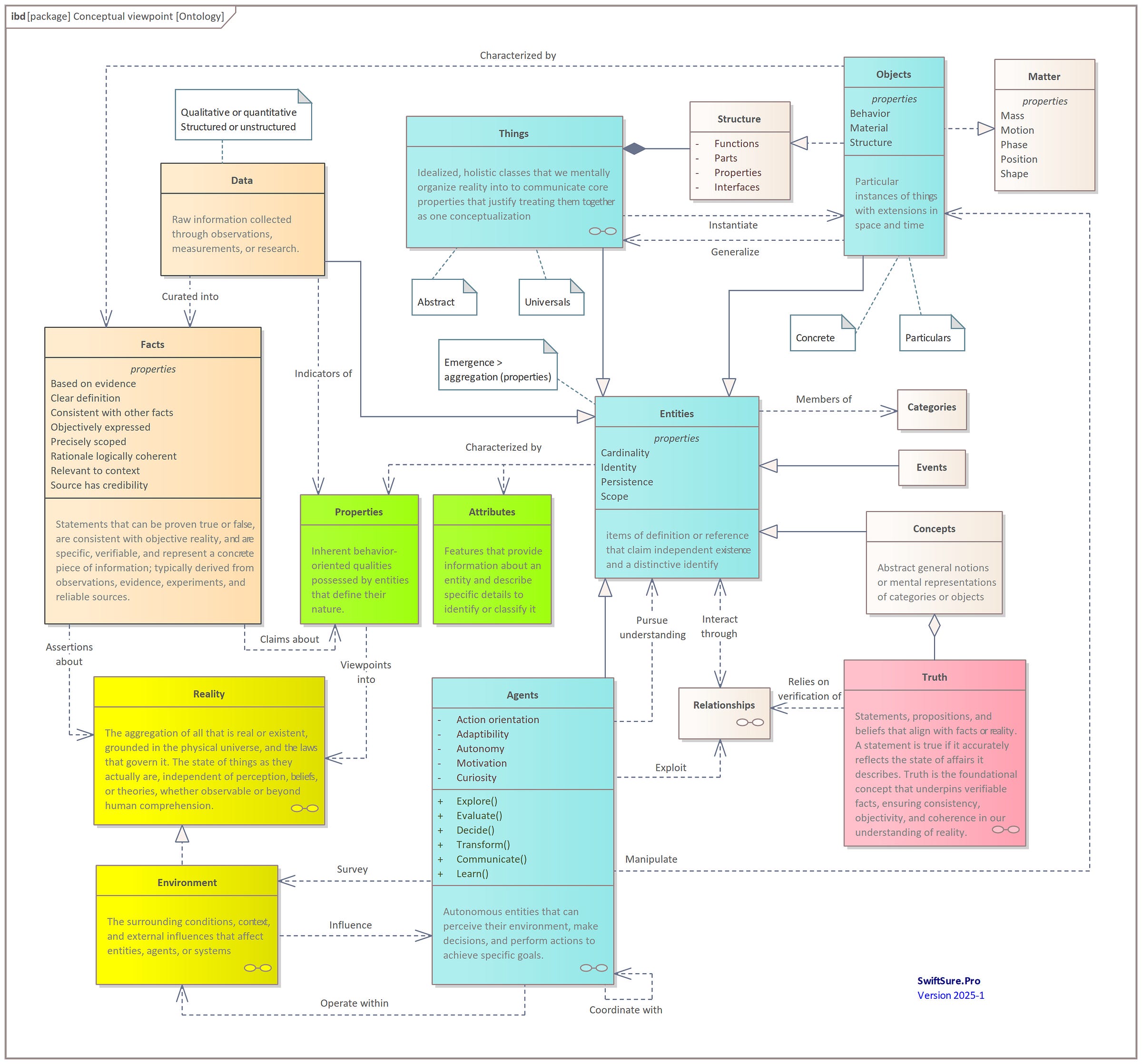

Figure 1 presents key names and relationships of entities that I will be using in this blog, so that ideas I present herein can be evaluated from a firm philosophical foundation.

Ontologies organize elements (data, facts, entities, objects, and concepts) into a relational hierarchy, connecting how we observe, describe, interpret, and act upon the world. They facilitate precision in classification, which is especially useful in modeling real-world systems, AI reasoning, and philosophical analysis.

Figure 1 highlights the flow from perception (data) to understanding (concepts) to interactions (through relationships and agents). Naming a thing involves assigning it attributes, mapping it to categories, positioning it relative to other elements, and asserting authority, all central to the search for ground truth and meaning. A few examples will help amplify these ideas.

A modern case study

Clayton Christianson is widely recognized as one of our most influential thinkers on innovation theory and practice. While he is most famous for his classic book The Innovator’s Dilemma, his more recent book, Competing against Luck, is my favorite. It’s his answer to the dilemma he identified in his earlier work, which describes why most companies miss innovation opportunities: successful companies with established products focus on extending the features of those products rather than cannibalizing that business for more visionary frontiers. In this passage, he defines jobs in customer rather than product terms:

…customers don’t buy products or services; they pull them into their lives to make progress. We call this progress the “job” they are trying to get done, and in our metaphor we say that customers “hire” products or services to solve these jobs…

We define a “job” as the progress that a person is trying to make in a particular circumstance. This definition of a job is not simply a new way of categorizing customers or their problems. It’s key to understanding why they make the choices they make. The choice of the word “progress” is deliberate. It represents movement toward a goal or aspiration. A job is always a process to make progress, it’s rarely a discrete event. A job is not necessarily just a “problem” that arises, though one form the progress can take is the resolution of a specific problem and the struggle it entails…

Second, the idea of a “circumstance” is intrinsic to the definition of a job. A job can only be defined—and a successful solution created - relative to the specific context in which it arises.

Christensen’s redefinition of a “job” reflects how ontologies define functions, roles, and intentionality. From Christensen’s viewpoint, jobs aren’t static identifiers but instead are dynamic roles situated in circumstances. This aligns with the ontological modeling of events, agents, and goals shown in Figure 1. Defining a customer or agent’s role (their “job”) influences how their needs and strategies are framed, a prime example of how terminological precision influences system behavior.

Endeavor as an umbrella term

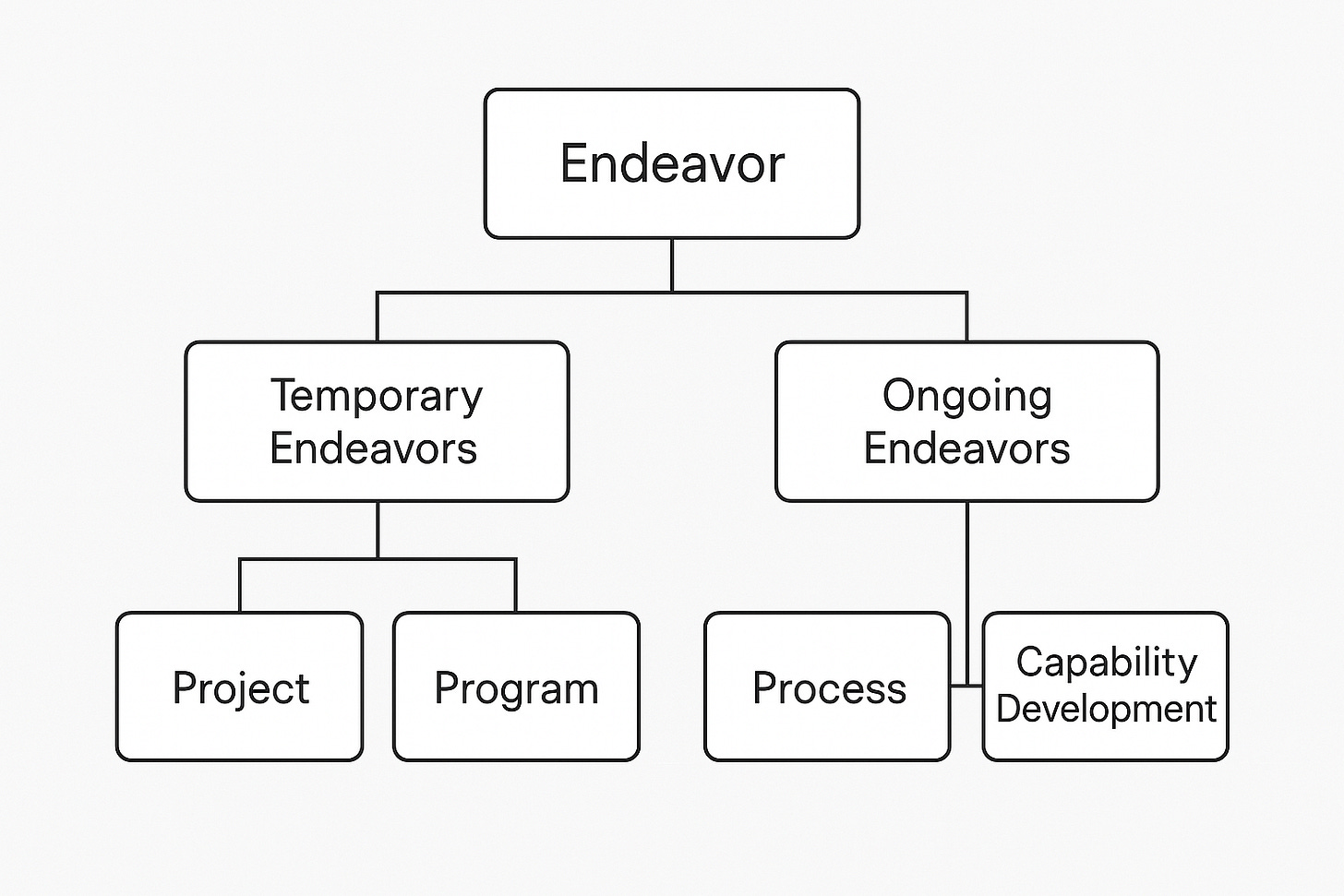

The word endeavor is an abstract concept that is often used as a broad umbrella term in the context of projects, programs, and processes, It serves as a kind of superclass that captures any purposeful, goal-oriented effort. It’s especially common in project management, where the PMBOK Guide defines a project as “a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result”. Figure 2 depicts this structure.

An endeavor in this context is thus a structured, intentional effort to achieve a specific outcome, often involving planning, coordination, and resource allocation. It’s a flexible term that can encompass:

Projects – temporary, unique efforts with defined scope and timeline

Programs – coordinated groups of related projects managed together

Processes – ongoing, repeatable sequences of activities that produce consistent results

Capabilities - the methods, tools, and competencies (“How-to”) that enable resources to be used effectively in accomplishing a specified course of action

Why use the term endeavor at all? Because it’s neutral and inclusive. It doesn’t assume:

Whether the effort is short-term (like a project) or ongoing (like a process)

Whether it’s standalone or part of a larger system

Whether it’s formalized or informal

That makes it useful when I want to talk about all kinds of purposeful work without getting bogged down in such details. It also enhances the reach of propositions associated with endeavors.

Why is this blog named SwiftSure.Pro?

When I began working at Boeing, my group had several sailing enthusiasts. Long-distance sailing challenges participants to demonstrate their preparation, navigation, and sailing skills, while competing against other boats, weather, and equipment problems. One of their favorites was the Swiftsure International Yacht Race, which since 1968 has been run regularly from Victoria, BC around Swiftsure Bank (at the entrance to the Juan de Fuca Strait) and is the pinnacle of ocean racing in the Pacific Northwest. It is also a warmup for the much longer 2300nm Vic-Maui race.

The name SwiftSure runs deep in oceangoing currents, from gunships to submarines and even lightships. Starting in 1909, Lightship #93 was a US Coastguard lightship that was stationed at the Swiftsure Bank - where the Swiftsure Cup Races turn.

The domain name swiftsure.pro itself is a blend word that combines appealing, powerful, and complementary concepts for system development and operation. The “.Pro” top-level domain is derived from professional, indicating its intended use by certified professionals. But its Latin root productio means “to bring forth” or “to lead forward.” Pro is thus a directional force, and its suffix determines what’s being led forward - a product, a person, a promise. Production thus aligns with operational emergence by bringing capabilities into form, whereas professional aligns with strategic representation by declaring mastery within a domain.

Speed is a desirable attribute in this pursuit since such strategic advantages can overwhelm competitors and increase opportunities for progress. The Agile methodology tries to blend this speed with adaptability, attempting more than just being “quick,” but “quick to change, pivot, rebound.” It suggests nimbleness under uncertainty: an agile dancer weaving through the crowd, or an agile team adapting to new requirements. There’s a flexibility baked into the term.

Yet speed in the wrong direction is wasteful, and demonstrations of progress can suffer when instability rears its head. Instead, the concept of swiftness speaks of the combination of speed and smoothness, delivering rapid action with precision and grace. It feels decisive and final: a swift stroke, a swift reply. It evokes confidence that whatever happens, it happens fast and cleanly. You’d call a falcon’s dive “swift,” or praise a customer service team for “swift resolution” of a ticket. The emphasis is on rapid execution.

The second of our blend words, “Sure”, brings a different dimension. As an adverb, it describes something or someone as guaranteed, certain, or self-possessed. It can signal an external guarantee (“delivery is assured”) or an internal composure (“an assured manner”). As a noun, it also means confidence, an internal sense of trust or belief in one’s abilities, in someone else, or in the reliability of a thing.

My goal in naming this site as indicated is to help bring these ideas into being for others - to provide information to build confidence in bringing forth results rapidly and smoothly. A novel structure to aid that pursuit is here.

How are taxonomies useful?

Clear definitions can help improve understanding, but only if they are used consistently. Here are several examples of the confusion that can arise when definitions are not consistently applied, taken from Barry Boehm’s book, Balancing Agility and Discipline:

Probably the easiest source of perplexity to identify, and perhaps the most difficult to resolve, is that of multiple definitions for the same word. For example, the term disciplined, whose dictionary definition includes both “common compliance with established processes” and “self-control,” is confined to process compliance by CMM bureaucrats, and confined to self-control by agile free spirits. Similarly, agility has been selectively interpreted positively as “dexterity” and negatively as “inconstancy of purpose.” A further example is quality. In the SW-CMM, “quality assurance” is defined as “specification and process compliance.” Agile methods see quality as essentially customer satisfaction.

Pursuing such consistency is the hallmark of taxonomies, which promote a consistent alignment of definitions for classifications, categorizations, and naming of the entities they represent.

Taxonomies are crucial in domains like project management, knowledge architecture, and systems design. At its core, a taxonomy is an organized classification system that arranges concepts, entities, or components into hierarchical relationships based on shared characteristics. It’s like a mental scaffolding that helps us navigate complexity by breaking it into digestible categories.

In systems thinking, taxonomies allow us to:

Surface interdependencies, by seeing where elements sit in a larger structure

Diagnose problems at the right level (don’t treat a process problem as a project failure)

Design feedback loops by recognizing roles and relationships between layers

It’s also how we can avoid confusing symptoms for causes and make smarter interventions.

With that in mind, a taxonomy for this site is here, in which I will capture definitions such as in Figure 1 - and for ideas developed throughout my posts - which will be updated periodically.