On truth

'The truth is rarely pure and never simple.” ― Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest

Truth is the conformity of our judgments to the reality of things. It is the agreement of our ideas with the objects they represent. This truth is revealed to us through the inspiration of ideas, the progressive unfolding of evidence and the application of reason, which provides us with the ability to understand the relationships among ideas and connect causes with effects.

Our understanding of those connections and their dynamics enables us to align our will, viewpoints, and behaviors accordingly, and use them to develop a layered, interconnected depiction of reality, where every element informs and potentially transforms. Truth is therefore not a property of words or sentences, but of the minds that forms them and the things those minds are intended to signify.

The pursuit of truth is thus the noblest occupation of the human mind. It is the pursuit of philosophy and science, the glory of religion, the foundation of virtue, the rule of conduct, and the bond of society. Since this concept is so critical to our understanding of the world, it is worth a deep dive into its underlying metaphysical meaning.

Deep dive into context

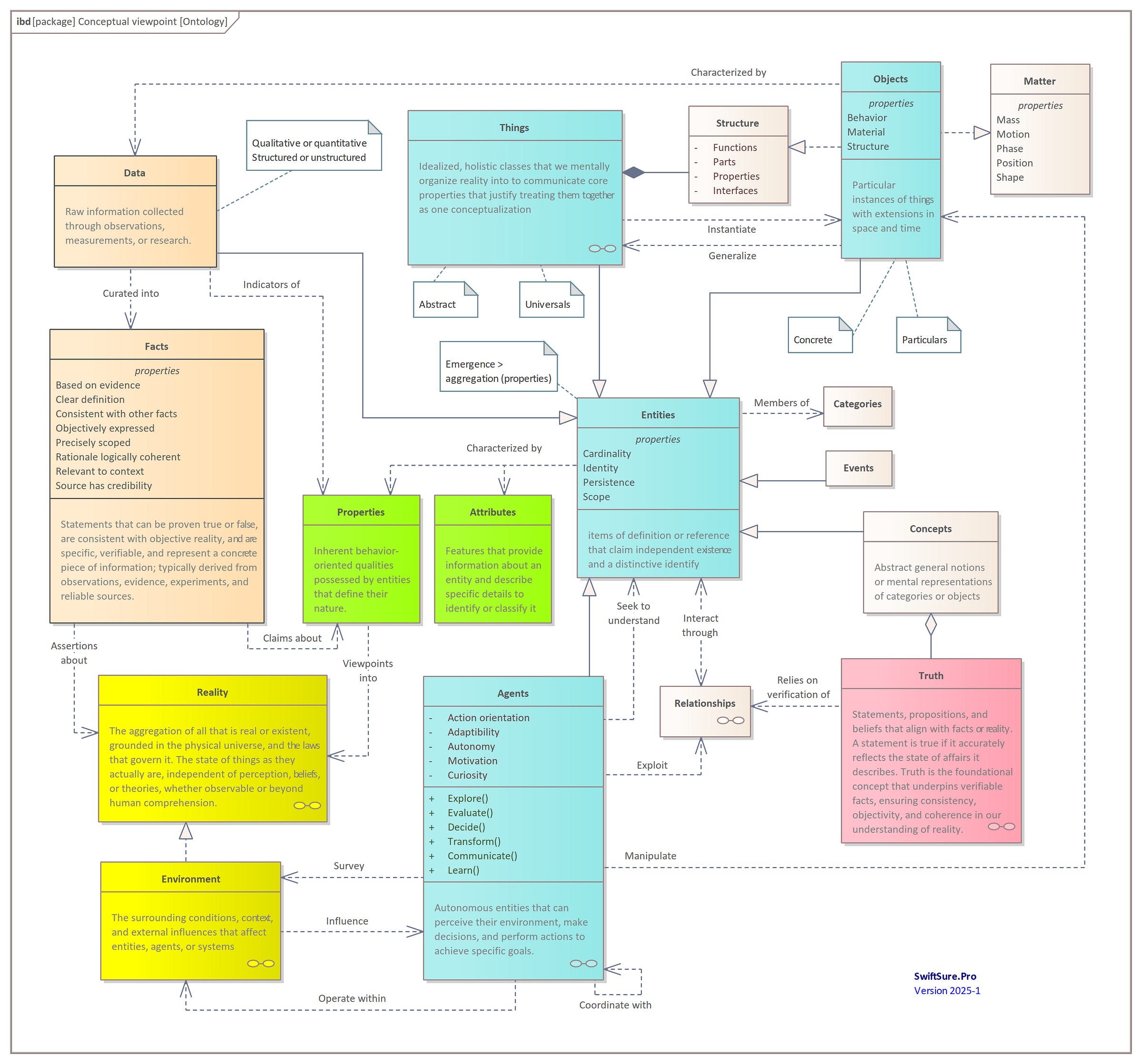

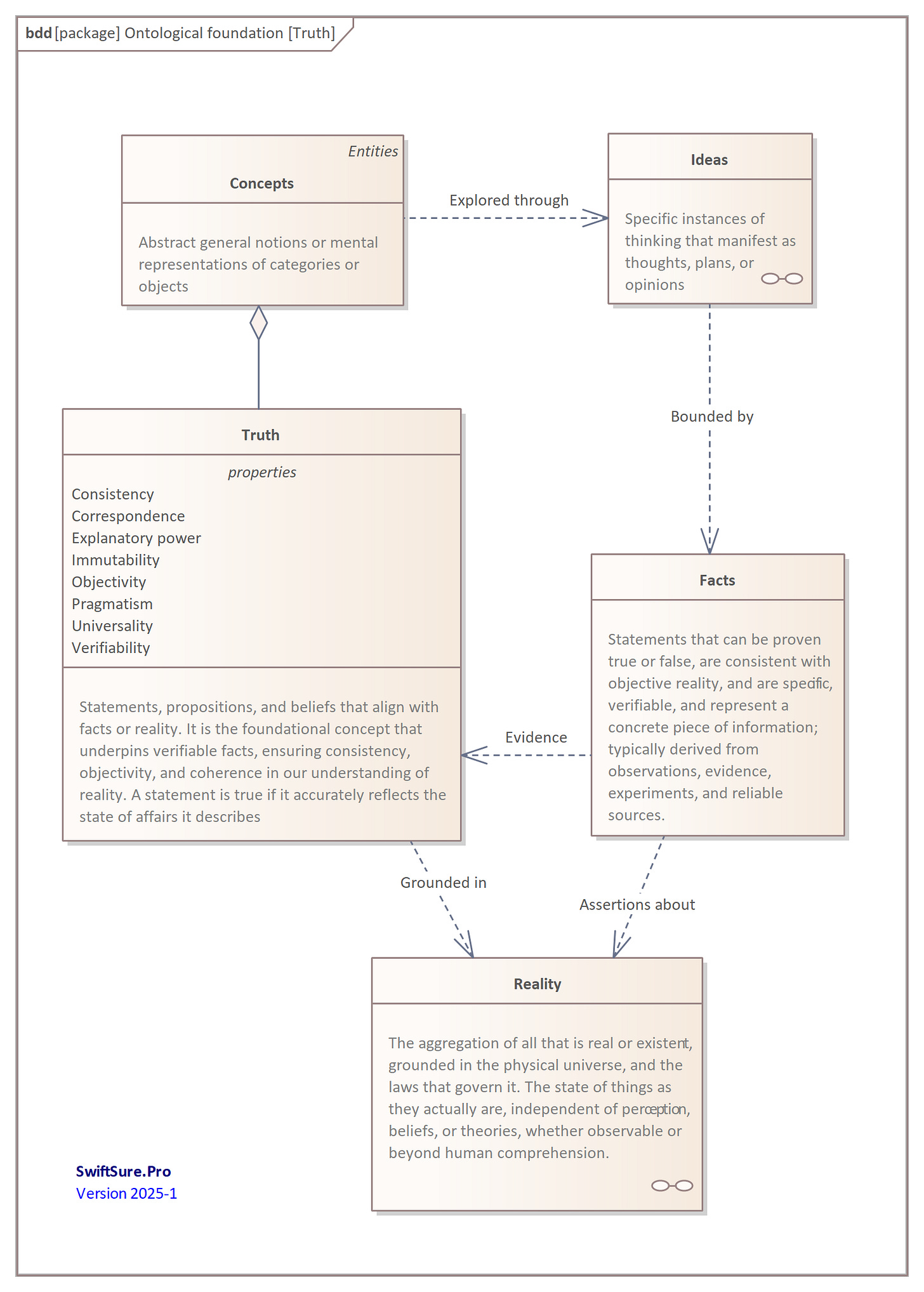

Our notions of truth depend upon a complex web of relationships among ideas (see figure 1). For a formal definition, see the red box.

Let's break down the notations1 and relationships depicted in this diagram. At its core, the figure provides us with a conceptual map that organizes the various elements in classical Metaphysics within an Oncology, which Wikipedia provides an excellent summary of (paraphrased below); the curious may be interested in exploring some of the links to discover the diversity of philosophical thought behind many of these ideas.

Ontology is the philosophical study of being. […] To articulate the basic structure of being, ontology examines the commonalities among all things and investigates their classification into basic types, such as the categories of particulars and universals. Particulars are unique, non-repeatable entities, such as the person Socrates, whereas universals are general, repeatable entities, like the color green. Another distinction exists between concrete objects existing in space and time, such as a tree, and abstract objects existing outside space and time, like the number 7. Systems of categories aim to provide a comprehensive inventory of reality by employing categories such as fabric, properties, relations, states of affairs, and events.

Each element in Figure 1 is connected through a web of relationships that enable us to form a coherent view of our world:

the boxes on the diagram depict concepts. Each concept has definitions (shown inside the boxes) and attributes (+ signs designate the name of each attribute).

Some boxes depict agency, by highlighting the operations they perform; these have parenthesis attached to the name of each operation (see for example Explore under Agency)

The arrows on the diagram depict the type of relationship between concepts, with distinct types of arrows depicting distinct types of relationships2.

The eyeglass symbol means there are lower-level diagrams which illuminate the topic further.

Here are key points about the elements using these relationships:

Data and Facts (see boxes in light brown)

Data are curated into facts, the foundational building blocks for constructing a reliable view of reality.Data are the raw observations or measurements - unrefined information - that are collected from the world.

Facts are the verified, contextualized pieces of information derived from this data. Raw data only becomes meaningful once statements about their properties, behaviors, etc, are verified to be consistent with reality.

Entities, Things, Objects, and Agents (in light blue)

Entities are the building blocks that objects, agents, and conceptual elements (things) are refined from.Entities are distinct items with unique identities. They have defined existence and can be counted or referenced uniquely. Note that many of the lines connecting the Entities block to other blocks have a colored, filled arrowhead. This is an generalization relationship, indicating the element at the end of the arrowhead is an abstraction of the item at the starting point of the arrowhead, including each of the following:

Things are abstract, holistic constructs that help us organize our conceptualization of reality. Think of a “thing” as a core concept that defines a category based on shared properties or characteristics.

Objects are concrete manifestations or instances of these abstract things. They exist in space and time and carry physical or perceptible qualities that allow us to experience them directly.

Agents are autonomous entities capable of perceiving and acting within the context they operate within. They interact dynamically with objects by making decisions based on the information provided by their properties and relationships.

Properties and Attributes (in light green)

Both properties and attributes articulate the essence of entities. They are how we describe and differentiate one entity from another by defining the nature and specifics of each thing or object.Properties refer to the inherent qualities or behaviors associated with an entity, such as describing what an object does or what natural characteristics it possesses which cause it to fall into this category.

Attributes define descriptors that enable the identification or classification of an entity, thus delineating the distinguishing characteristics that set one entity apart from another.

Reality and the Environment (in yellow)

Reality serves as the overarching framework in which facts, objects, agents, and their characteristics and relationships exist and evolve. A drill-down into the categories of reality are here.

The environment provides the context and external forces that influence how agents behave and objects evolve, providing the backdrop against which all interactions occur, thereby offering both possibilities and constraints.

Additional elements such as categories, events, and concepts serve to further contextualize these entities. For instance, the insight that an entity may belong to a category or perform a role relating to an event may deepen our understanding of how agents interact with the world.

The aim of truth

Overall, Figure 1 depicts a flow from raw data to actionable facts, from abstract things to tangible objects, and from simple properties and attributes to complex agents navigating a potentially hostile environment. Let’s use these ideas to dive further into this viewpoint of the definition of truth:

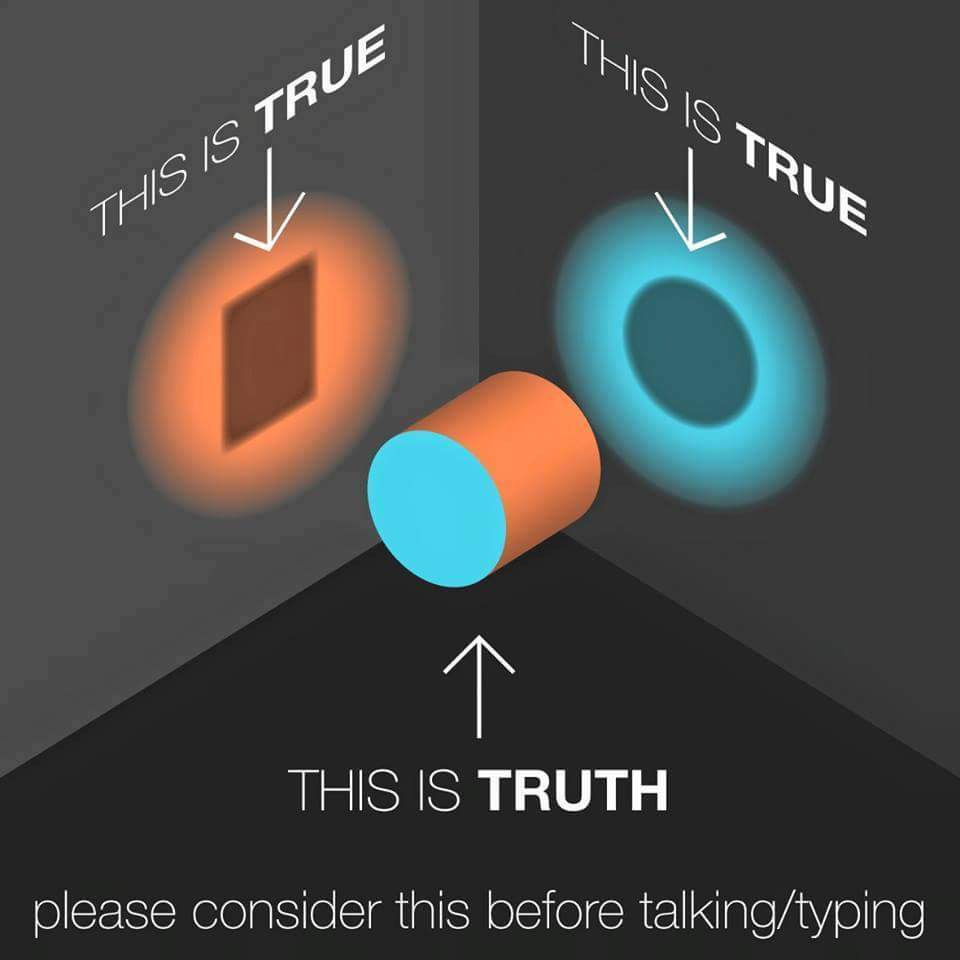

The attributes described in Figure 2 are the ingredients necessary for accurately describing the reality to which it refers. As a concept, however, it must be recognized that truths are rarely absolute (see Figure 3). Instead, they rely upon facts that are typically relevant within contexts which may shift with time. Declaring that an idea is true without providing the evidence and attributes that warrant such a claim is an appeal to power and ideology rather than substance, logic, and objectivity.

Implications for action

Here are some effective ways to fuel the discovery of truth within this landscape:

Test ideas against reality. One way is through the correspondence approach, which means to test your ideas against observations of the world. You can do this by forming hypotheses, collecting data, conducting experiments, and applying logic to your arguments. This is the method of science, which aims to discover the natural laws that govern the universe. However, this approach also has its limitations, such as the problem of induction, the role of interpretation, and the influence of paradigms.

Seek coherence and insight. Another way to pursue truth is to use the coherence approach, by looking for the consistency and harmony of your ideas. You can do this by examining the concepts behind the idea and their relationships to reality, finding patterns and connections, and trying to move from understanding to the ability to project them into other settings. This is the method of philosophy, which aims to construct a comprehensive and ordered view of the world. However, this approach also has its challenges, such as the problem of circularity, the role of intuition, and the influence of perspectives.

Seek authenticity and self-awareness. A third way to pursue truth is to use a phenomenological approach, by focusing on your own experience and perception of the world. You can do this by being mindful of your feelings, thoughts, and actions, and expressing your true self. This is the method of psychology, which aims to explore the human mind and behavior. However, this approach also has its difficulties, such as the problem of subjectivity, the role of emotions, and the influence of biases.

There are other ways to pursue truth, such as the foundational, pragmatic, or relativist approaches suggested by various philosophers. But for personal pursuits of truth, the important thing is to be curious, open-minded, and humble in your quest for truth. As Socrates said, "The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing."