A scorecard of popular frameworks

In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is. - Yogi Berra

There are plenty of competing frameworks that promise successful outcomes for endeavors. The Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle, which has its roots in the scientific method (Hypothesis-Experiment-Evaluation) and Bell Labs’ Shewart Cycle (Specification-Production-Inspection) come to mind, but all lack needed context to organize efforts around the problem being solved. Most lean heavily into planning. The book How Big Things Get Done provides a useful orientation for this foundation:

“Planning” is a concept with baggage. For many, it calls to mind a passive activity: sitting, thinking, staring into space, abstracting what you’re going to do. In its more institutional form, planning is a bureaucratic exercise in which the planner writes reports, colors maps and charts, programs activities, and fills in boxes on flowcharts. Such plans often look like train schedules, but they’re even less interesting. Much planning does fit that bill.

And that’s a problem because it’s a serious mistake to treat planning as an exercise in abstract, bureaucratic thought and calculation. What sets good planning apart from the rest is something completely different. It is captured by a Latin verb, experiri. Experiri means “to try,” “to test,” or “to prove.” It is the origin of two wonderful words in English: experiment and experience.

Plan-driven methods

Professional societies offer plenty of guidance about this experiential experimentation. Since 1969, the Project Management Institute has championed plan-driven methods that promise to produce a robust project plan. Unfortunately, the robustness often drags along an accompanying bureaucratic overhead with it. Many other disciplines, like systems engineering and software engineering, echo significant elements from PMI’s framework.

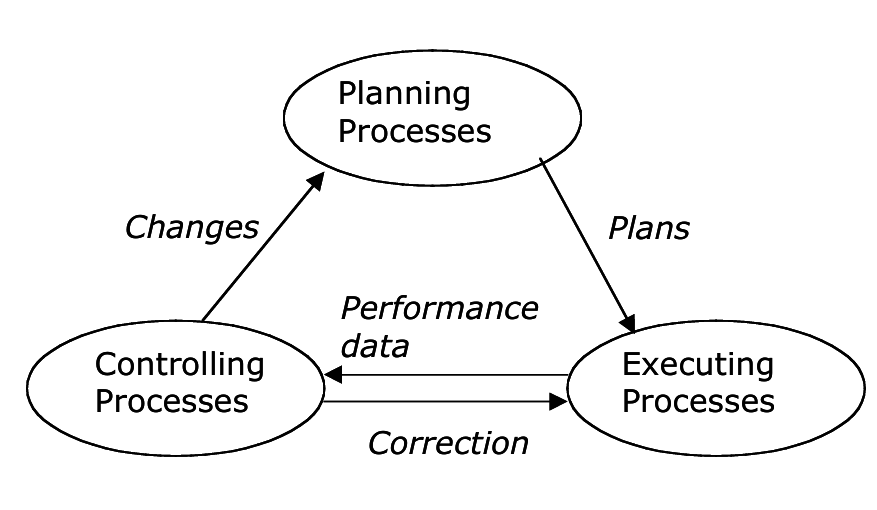

Figure 2 captures the major processes in the Project Management Body of Knowledge Guide (PMBOK), with planning processes getting most attention, and plans being the primary output.

There are ten core elements of the planning process: scope planning, scope definition, activity definition, resource planning, activity sequencing, activity duration estimating, cost estimating, schedule development, cost budgeting, and project plan development. In comparison, there is only one executing process and two controlling processes, so the primary output of project management is the project plan, which itself risks becoming bureaucratic. Quoting the PMBOK:

The definition and management of processes is key to plan-driven methods. For that reason, plan-driven methods are almost always associated with process improvement. The processes need to be defined, standardized, and incrementally improved to provide the data needed to control and manage their operation. Such processes generally include detailed plans, activities, workflow, roles and responsibilities, and work product descriptions.

Thus, learning and improvement are expected to be a fundamental feature built into project plans, though these attributes often rely on activities outside the scope of the resulting plan.

In its most recent incarnation, the PMBOK has placed an increased emphasis on principles, which are worthwhile, unsurprising, and easier said than done. This is a positive step away from a strict control orientation (note, for example, the guidance on the project manager chief role responsible for coordinating project activities). Several concerns about the PMBOK remain:

Structural rigidity and lack of flexibility

Prescriptive nature: PMBOK has traditionally emphasized rigid processes and documentation, which can hinder adaptability in dynamic or innovative projects.

Slow to adapt: Critics argue that PMBOK struggles to keep pace with rapidly changing business environments, especially in tech and creative sectors.

Documentation focus and administrative burden

Heavy emphasis on documentation: While useful for compliance and audits, extensive paperwork can create unnecessary overhead, particularly for small endeavors.

Process-centric bias: The focus on process groups and knowledge areas may lead to bureaucratic inefficiencies in fast-moving projects.

Insufficient emphasis on sustainability

Sustainability gaps: While PMBOK mentions sustainability, it lacks actionable frameworks for integrating related concepts into project success criteria.

Lifecycle sustainability: Critics call for sustainability to be embedded throughout all project phases, not just acknowledged in theory.

Underutilization of AI and Data-Driven Decision Making

AI as an afterthought: PMBOK has been slow to embrace AI as a strategic partner in project planning, risk assessment, and communication.

Missed opportunities: Tools like generative AI and machine learning could enhance forecasting, stakeholder engagement, and adaptive planning, but are not yet central to the PMBOK framework.

Challenges with Distributed Teams and Modern Collaboration

Limited guidance for remote and distributed teams: PMBOK has traditionally focused on co-located teams and hierarchical structures, which may not reflect today’s collaborative, networked environments.

Disconnects between conceptual and practical elements

Theory-heavy: Some practitioners find PMBOK too abstract or academic, lacking practical tools for real-world challenges.

Principles vs. execution: The shift to principles-based guidance in newer editions aims to address this, but implementation clarity remains a concern

Plan-driven methods are themselves production processes which are expected to facilitate tradeoffs across alternative approaches for activities, confront tensions between autonomy and control, and transform inputs into outputs within whatever organizing framework has been adopted for activities. The Origins of Efficiency outlines the challenging circumstances of production:

Production processes are sociotechnical systems, embedded in human organizations and subject to the vagaries of human decisions, which are often guided by considerations other than cost. These decisions can and do influence the trajectory of production process development, by adding costs in service of achieving other goals like increasing safety or reducing environmental harms, or by limiting the sorts of improvements that can be made.

Information is an input needed, and an output produced, by most production processes. When we think of planning as itself a production process, the is often operating in the realm of ideas, narratives, and concepts, often (much of it unreliable), assumptions (when information is unavailable), and predictions of forward-looking behaviors (which are subject to biases), all under time pressure that often limits a necessary understanding of the presenting situations of the endeavor.

Agile

Agile software development emerged in 2001 and provides an iterative, incremental, and evolutionary framework which embraces values and principles appeal to small teams. Since then, many separate methods have emerged that share DNA with these ideas, while seeking differentiation across the competitive environment they operate within; an ocean liner of businesses (including many led by Agile Alliance members) emerged ready to offer their services and combat the common pitfalls encountered with these methods. Yet studies on failed transformations highlight preparation issues: - lack of leadership, inadequate sponsorship, unclear decision rights, misaligned incentives, rigid governance structures, ow psychological safety, and poor cross-functional collaboration.

Many Agile-focused methods have also been embraced in applications outside software development, with limited success. Scaling up agile to major development efforts (100+ developers working on a specific product) and in regulated, safety-focused endeavors has also proved challenging.

Steve McConnell’s book, More Effective Agile offers the following contrasts between plan-based, sequential methods like PMBOK and adaptive methods like Agile:

Comparisons of Agile and plan-driven methods often contrasted failed plan-driven projects with successful Agile projects, or vice versa. Since all successful projects rely upon effective organization and oversight, customer collaboration, and robust transformations, such comparisons are rarely useful.

One of my favorite books evaluating improvement frameworks is Balancing Agility and Discipline. It describes the tension between these two competing worldviews:

The agilists rail against the traditionalists and lament the dehumanization of software development by “Taylorian” reductionists who worship process. The establishment has responded with accusations of hacking, poor quality, and having way too much fun in a serious business. True believers on both sides have emerged to proclaim their convictions with near-messianic stridency, raising the perplexity level of software developers and managers trying to evolve their success strategies.

At the ten-year anniversary of Agile’s Manifesto, Philippe Kruchten captured the ‘elephant in the room’ nature of issues which the participants reflecting on. A sample of his thoughts deserve repeating:

While the community has been good at amplifying what works, it often has not been good at dampening what did not work, analyzing why it did not work, or under which conditions it did not work (context!)…

In most instances, when practices are described too little of the actual context is described, leaving an impression of very wide applicability; even if this wide applicability is not actually claimed. Sometimes this is just pure dogmatism, or bigotry…

Unlike other disciplines, like medicine for instance, there is very little reporting of failures or limitations in software, and no clear venue or even templates or exemplars of such reporting. And again the fear that this would reflect badly on the person reporting, or the “victim” or “culprit” organization. A good template for such report would include a detailed description of the context…

There are still too few people gathering objective, significant, scientific evidence on our practices, except for a very few that are easy to instrument (pair programming, for example)…

The agile movement is in some ways a bit like a teenager: very self-conscious, checking constantly its appearance in a mirror, accepting few criticisms, only interested in being with its peers, rejecting en bloc all wisdom from the past, just because it is from the past, adopting fads and new jargon, at times cocky and arrogant.

Continuous flow

The book The Origins of Efficiency highlights one of the primary constraints limiting both plan-driven methods and Agile: they simply do not scale:

When we take a 30,000-foot view at where and how efficiency has improved, one recurring theme is the importance of scale. Economies of scale are not only a major driver of efficiency improvements in and of themselves, but they are also a gating mechanism that unlocks other efficiency improvements by making it possible to amortize the large fixed costs that such improvements often require over a sufficiently large output…

When we can’t repeat a process, or when there’s significant variation in the production environment or in the product itself, many paths toward increased efficiency are blocked. Without repetition, we can’t take advantage of economies of scale. A constantly changing process or a highly variable environment is harder to predict and control, making it more difficult to increase yield and decrease waste. It’s also harder to automate or mechanize in such circumstances, which limits our ability to reduce labor costs. This is one reason why services like medical care, car repair, and construction, which rely on skilled labor that can flexibly adapt to highly variable conditions, remain expensive. Finding ways to make these things cheap will require escaping the constraints of scale to get the benefits of a continuous process—that is, a constant transformation of inputs into a finished product without waiting, buffering, failures, or wasted actions—without needing to repeat that process over and over again…

The development of continuous processes has historically been most easily achieved with a carefully orchestrated arrangement of workers and special-purpose equipment, which is costly to build and operate and, therefore, requires the cost to be spread over a very large output. It takes time, effort, and expense to make the steps in a process work together in sync, a result that can often only be achieved with dedicated equipment and justified with large production volumes…

What if it was quick and easy to figure out the order of steps in a process and arrange them so that the transformation is swift and steady? And what if this process didn’t require special equipment but could use flexible, adaptable machinery able to produce a variety of different items? Then it would be possible to achieve a smooth continuous process that worked in a highly variable environment, bringing the benefits of efficiency improvement to domains that have traditionally resisted it…

For production technology to be able to flexibly adapt to a highly variable environment, there are two broad requirements. First, it requires [methods and] equipment that is physically capable of responding flexibly—that can take a broad range of possible actions, or a small number of actions that can be combined to produce a wide variety of outputs…

The second requirement for flexible, automated production is that the equipment has some method of determining the sequence of the proper actions to take—an information-processing component that can, based on data from the environment, break a desired output into a series of achievable production steps.

The capabilities available from satisficing these requirements will be considerably enhanced as artificial intelligence technologies are incorporated into activities and allow dynamic reallocation of efforts to maximize achievable outcomes.

Operations focus

Neither Agile nor plan-driven methods provide the universal flow-oriented viewpoint for production that is offered by Lean (an extension of the Toyota Production System). Lean and JIT (Just-In-Time) methods emerged from industrial engineering with a queueing-theory backbone, pushing teams toward dynamic flow while retaining and customer focus.

However, Lean lacks the disciplines of plan-oriented methods, since it is designed for improving operations; further, its focus on elimination of waste can shortcut strategic efforts. As a result, Lean-Agile hybrids have been effective in industries that require both operational excellence and rapid innovation. These hybrids typically feature adaptive planning with feedback loops, pull-based scheduling, visual management techniques, and continuous improvement concepts with a customer-value focus across cross-functional teams.

Analysis

Well-established professions typically build their concepts around theoretical foundations. In The underlying theory of project management is obsolete, the authors recognize that production has many manifestations:

… competing theories of production (projects are just special instances of production) have existed even before the emergence of project management. Another concept of production was presented already in the framework of early industrial engineering. The flow view of production … is embodied in JIT and lean production. In a breakthrough book, Hopp and Spearman (1996) show that by means of the queueing theory, various insights, which have been used as heuristics in the framework of JIT, can be mathematically proven.

While Lean concepts rely on this theoretical foundation, and have recently gained traction among startups, they have had their greatest success fighting ‘big company disease’, through a focus on customer concerns and a systems approach across collaborative teams. Their biggest contribution has been helping to change thinking from a static plan-oriented focus to a dynamic flow-oriented model.

Let’s break down the features of each of these frameworks, drawing from this analysis:

If the reader studies this table, they may conclude no single option provides what they need.

Hybrid approaches

Hybrid approaches, while appealing, aren’t a panacea; common pitfalls include overhead and complexity, fragmented communications, dilution of core principles, tooling challenges, inconsistent metrics, and the ever-present resistance to change. Examples cited in the literature include:

Teams using sprints but still following rigid upfront planning, losing Agile’s adaptability

Isolated Agile adoption in which Agile is adopted locally but is not supported or compatible with other departments frameworks, creating delivery misalignment

Organizations cherry-picking practices and adopting Agile rituals (like stand-ups) without embracing its principles, often resulting in limited adaptability

Lean’s reliance on accurate forecasting clashes with Agile’s responsiveness, especially in volatile markets.

This is made worse when one realizes that few endeavors fully implement all the features in their situation, so relying on a hybrid puts the user in the difficult role of integrating parts designed for separate purposes on their own.

The bottom line:

The idea of a fixed method, or a fixed theory of rationality, rests on too naive a view of man and his social surroundings - Paul Feyerabend, in Against Method

In the next post in this series, we will confront the inevitable tensions between desires for autonomy and control.

Regarding the topic of the article, your emphasis on experiri really resonates wirh the need for iterative, context-driven approaches in problem-solving, building effectively on your previous thoughts about practical application over rigid bureaucracy.