Tensions between autonomy and control

If communication cannot achieve consensus, we must live with the broken pieces of unfulfilled expectations and recognize the failure of dialogue, trust, and reciprocity. - Erik Pevernagie

In America, the tension between autonomy and control runs broad and deep. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton dramatizes this tension in the founding-era clash between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson (Figure 1). Hamilton is portrayed as a visionary who believes in a strong central government, national bank, and industrial economy. Jefferson is the agrarian idealist who argues for states’ rights and individual liberty.

The tension

Miranda’s musical celebrates Hamilton’s ambition and legacy, framing him as a hero of order and national coherence by favoring centralized, expert-led authority to tackle national problems like infrastructure, regulation, and technocratic governance. This pursuit often occurs in an atmosphere of Jeffersonian skepticism which champions local autonomy and individual liberty and is wary of elite control and centralized power. It’s a romanticized origin story of American governance, emphasizing the creative tension that forged the Constitution and early institutions.

The musical is an entertaining story, but reality is, as usual, more complicated than that. Marc J. Dunkelman’s Why Nothing Works explores why America, once capable of building massive infrastructure and social programs, now struggles to “get things done.” Everyone needs power but would prefer someone else to shoulder the burden of making that happen (Figure 1).

A case study

Dunkelman argues that endeavors often try to embody both of these impulses, which can lead to incompatible goals and conflicts. These conflicts can produce a vetocracy, where too many actors can veto action, stall progress and erode public trust. It creates a dynamic in which no one has the power or motivation to say “yes”, while anyone can delay and block action. The inevitable outcomes of these forces lead to repeated delays that can accumulate and result in cancellations.

This dynamic is highlighted in Chapter 8 of Dunkelman’s book, which uses electrical power distribution as a metaphor for the broader dysfunction in American governance. It illustrates how the tension between centralized control and decentralized autonomy undermines systemic reliability and reform. It also highlights the challenge of big ideas - for example, demanding national action on climate change (a Hamiltonian tendency) while resisting higher-level mandates that impinge on personal rights (the Jeffersonian approach).

In order for alternative energy sources to be developed, the means to transport that power from source to destination is crucial. The U.S. power grid evolved from a patchwork of local systems into a vast, interconnected infrastructure. Initially, power was generated and distributed locally, reflecting Jeffersonian ideals of community autonomy and responsiveness. But as demand grew and industrialization accelerated, the need for centralized coordination became unavoidable. High-voltage transmission networks and regional interconnects were introduced - hallmarks of Hamiltonian planning - and enabled bulk power delivery across states, improving efficiency and reliability, and striving for balance between the benefits of competition and the stability of monopolies that are core characteristics of public utilities.

However, Dunkelman argues that this centralization of planning and control came at a cost, as local actors lost control of their property and resources, and the system became vulnerable to fragmentation and political gridlock. Regulatory agencies like FERC and NERC were created to oversee reliability and standards for these assets, but their authority is often undermined by state-level resistance, utility lobbying, environmental causes, and fragmented jurisdiction. The result is a paradox: while the grid requires Hamiltonian coordination to function, Jeffersonian impulses - manifested in local vetoes, fragmented oversight, and resistance to federal mandates -prevent necessary upgrades, especially in integration and resilience planning for renewables.

This tension is especially evident in ongoing efforts to modernize the grid. For example, building interstate transmission lines for wind and solar power requires federal coordination, but local communities often block projects due to land use concerns or political ideology. Since these sources of clean power require these transmission lines to transport power from producer to consumer, the dynamic erodes action on climate change while resisting the centralized authority needed to implement it. This contradiction mirrors the broader theme of the book: America’s inability to reconcile its founding impulses now paralyzes its capacity to solve big problems.

Progress, far from consisting in change, depends on retentiveness. When change is absolute there remains no being to improve and no direction is set for possible improvement: and when experience is not retained, as among savages, infancy is perpetual. Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. In the first stage of life the mind is frivolous and easily distracted, it misses progress by failing in consecutiveness and persistence. This is the condition of children and barbarians, in which instinct has learned nothing from experience. - George Santayana, The Life of Reason

Santayana highlights the importance of focus, experience, and learning over instinct. Just as Hamilton and Jefferson clashed over the role of government, modern America struggles to balance expert-led coordination with grassroots autonomy. Until this tension is acknowledged and addressed, Dunkelman warns, the nation will continue to suffer from systemic breakdowns—not just in electricity, but in governance itself.

A scorecard for traditional frameworks

There are plenty of competing frameworks that presume a control orientation, but all have limitations, and none provide explicit guidance for all the forces captured in the PIANOS model. It is worth stepping back and putting our system’s thinking hat on to understand why.

In their article Applying Systems Thinking to Engineering and Design, Monat and Gannon highlight the key principles of system thinking for production:

Holistic Perspective/Proper Definition of System Boundaries

Awareness that Events and Patterns are caused by Underlying Structures and Forces

Systemic Root Cause Analysis

Sensitivity to Emergent Properties

Sensitivity to Unintended Consequences

Dynamic Modeling

Focus on Relationships

Sensitivity to Feedback

Many endeavors employ these principles in practice, but none of the traditional frameworks explicitly seek to leverage these principles.

The dynamics

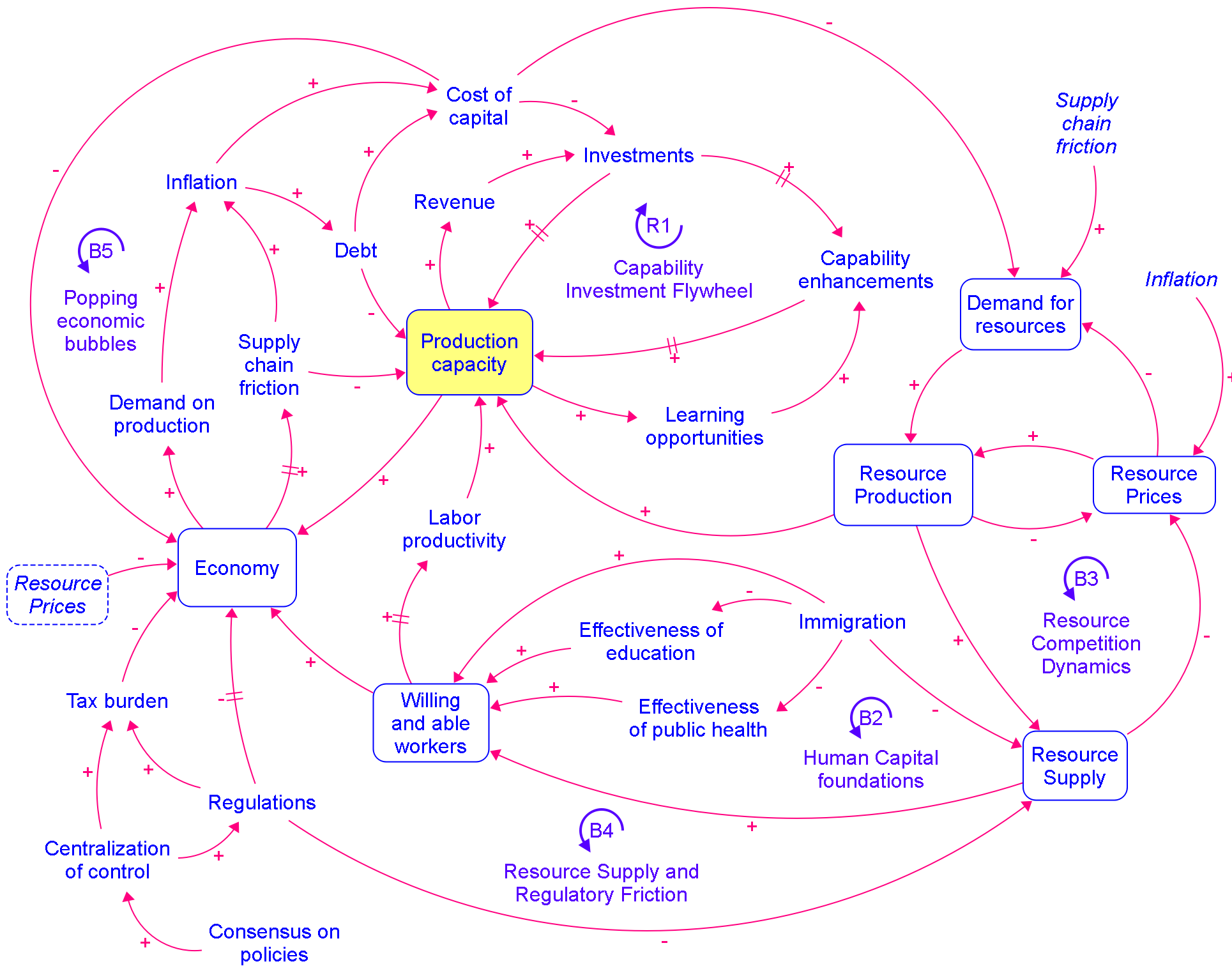

Let’s consider how dynamics of traditional frameworks unfold using the causal loop diagram shown in Figure 2. Such diagrams highlight the interactions of factors involved in achieving some result, in this case, the capacity of a production system. These interactions (labeled by the red arcs) have a polarity associated with each relationship, labeled with a plus or minus sign. This polarity indicates the influence one factor has on another - positive means ‘moves in the same direction’ and negative means ‘moves in the opposite direction. For example, the leftmost arc connects the cost of capital to the economy with a minus sign, meaning that in general (without considering other factors), when the cost of capital increases, the net effect will cause the economy to deteriorate. Alternatively, when the cost of capital decreases, the net effect will enhance the economy.

These factors also collectively form loops which accumulate the impacts of this polarity, and feed back to influence subsequent performance, leading to further growth or decline. These loops are labeled in the diagram with a prefix of R as reinforcing (creating growth) or B for balancing (leading to decline).

When building a simulation of these dynamics, the extent of each factor’s influence can be calibrated to match what is common knowledge, as long as the natural variation that accompanies each factor is taken account of.

The figure highlights the effects of resource contention - resources can be anything with enduring value, such as a home, a person’s health, and even their education. The ‘centralization of control’ factor in the lower left-hand corner is examined in more detail here. The running narrative for these interactions - applicable to any production system (whether governmental or industrial) - follows:

Loop R1: The Capability Investment Flywheel

At the heart of the diagram is a reinforcing feedback loop: production capacity increases → enabling more investments → which fund capability enhancements and learning opportunities → boosting labor productivity → which further expands production capacity. This loop reflects a virtuous cycle of growth, where reinvestment in human and technical capital drives compounding returns. It’s a Hamiltonian vision of centralized scaling through expertise and infrastructure.

However, when the economy takes a downturn - whether from a national crisis or demographic decline - this loop runs in reverse with limited options for recovery, all relying on the ability to attract buyers willing to finance additional investments with higher risk and lower returns.

Loop B2: Human Capital Foundations

This loop highlights how willing and able workers depend on upstream factors like:

Effectiveness of education

Effectiveness of public health

Immigration (as a labor supply enhancer)

These elements feed into labor productivity and ultimately production capacity. But they’re also shaped by regulations, tax burden, and centralization of control, which can either enable or constrain public investment. This loop shows how social systems and governance deeply affect economic output, underscoring the Jeffersonian tension between local autonomy and centralized policy.

Loop B3: Resource Competition Dynamics

Here we see a more complex, potentially destabilizing loop:

Rising production capacity boosts the economy, which increases resource demands → driving up prices.

Higher prices may stimulate resource supply, but also increase debt and inflation, which can negatively impact cost of capital and reduce investment.

This loop introduces negative feedback which can increase systemic fragility. It shows how economic growth can trigger affordability crises and financial instability, especially if regulatory and monetary systems fail to adapt.

Loop B4: Resource Supply and Regulatory Friction

Demand on production increases pressure on the supply of resources, which can be constrained by regulations and tax burden.

If these constraints are too tight, they reduce investment and slow the capability loop.

If too loose, they risk environmental degradation or inequality.

This loop captures the dilemma this poses for governance: balancing growth with sustainability and equity. It’s where Hamiltonian efficiency meets Jeffersonian caution.

Loop B5: Popping economic bubbles

Once irrational exuberance begins fueling a speculative bubble, the threat of future price increases begins to spur investor enthusiasm, causing a contraction in the economy. There will be winners and losers around this transition.

The dynamic tensions in systems

The diagram doesn’t offer a single solution—it models a dynamic equilibrium shaped by competing feedback loops.

Positive loops drive growth and innovation.

Negative loops introduce checks, risks, and social costs.

Governance levers (regulation, centralization, taxation) mediate these forces but are themselves contested and subject to dynamics.

The lower right factor Consensus on policies deserves elaboration. Consensus - the collective agreement or unified opinion reached by a group - doesn’t require unanimity, but it implies broad support or alignment. That only happens when leadership can orchestrate stakeholder negotiations and interests until a broadly acceptable solution emerges that everyone can live with. That relies upon a common understanding, acceptance, and support of the required tradeoffs which are necessary to realize the goal being pursued - all infused with patience for the dynamics to produce those results.

Achieving balance

In the Incremental Commitment Spiral Model, Barry Boehm emphasizes what he describes as The Fundamental System Success Theorem, which states: “A system will be successful if and only if it makes winners of its success-critical stakeholders.”:

One implication of the Fundamental System Success Theorem is that it is risky to use terms such as “optimize,” “minimize,” and “maximize” in project guidance. As Nobel Prize winner Herbert Simon showed in his book Models of Man, success in multiple-stakeholder situations is achieved not by optimizing, minimizing, or maximizing of individual criteria, but rather by satisficing with respect to the stakeholders’ multiple criteria.

To be accountable for a commitment, it is important to neither promise nor expect more than can be delivered. In a world of rapidly changing mission priorities, new technologies, competitive challenges, and organizational relationships, total commitment to the full details of a product to be delivered five years later is a very risky bet.

The term “satisficing” here means not everybody gets everything they want, but everybody gets an outcome that they can be satisfied with. Lacking such consensus, convergence on solutions may be fleeting, disappointing, and potentially overridden as power shifts with improved situational awareness, emerging political alliances, and new externalities drive dynamics. Adaptation is key to weathering this storm.

In the next post of this series, the scaffolding underneath these tensions is explored to lay the groundwork for understanding the common failure modes in endeavors. With these insights, you will be ready to practice how to avoid them.