Filling in the white space in endeavors

Every company has two organizational structures: The formal one is written on the charts; the other is the everyday relationship of the men and women in the organization." — Harold Geneen

In the intricate pursuit of organizational success, efficiency and structure often take center stage. Yet, hidden between the rigid frameworks of documented processes lies the "white space" - an uncharted territory where ambiguity, miscommunication, and missed opportunities thrive. This post explores how organizations can navigate these gaps, turning uncertainty into strategic advantage. By understanding the invisible forces shaping workflows, endeavors can foster adaptability, innovation, and resilience despite an ever-evolving business landscape.

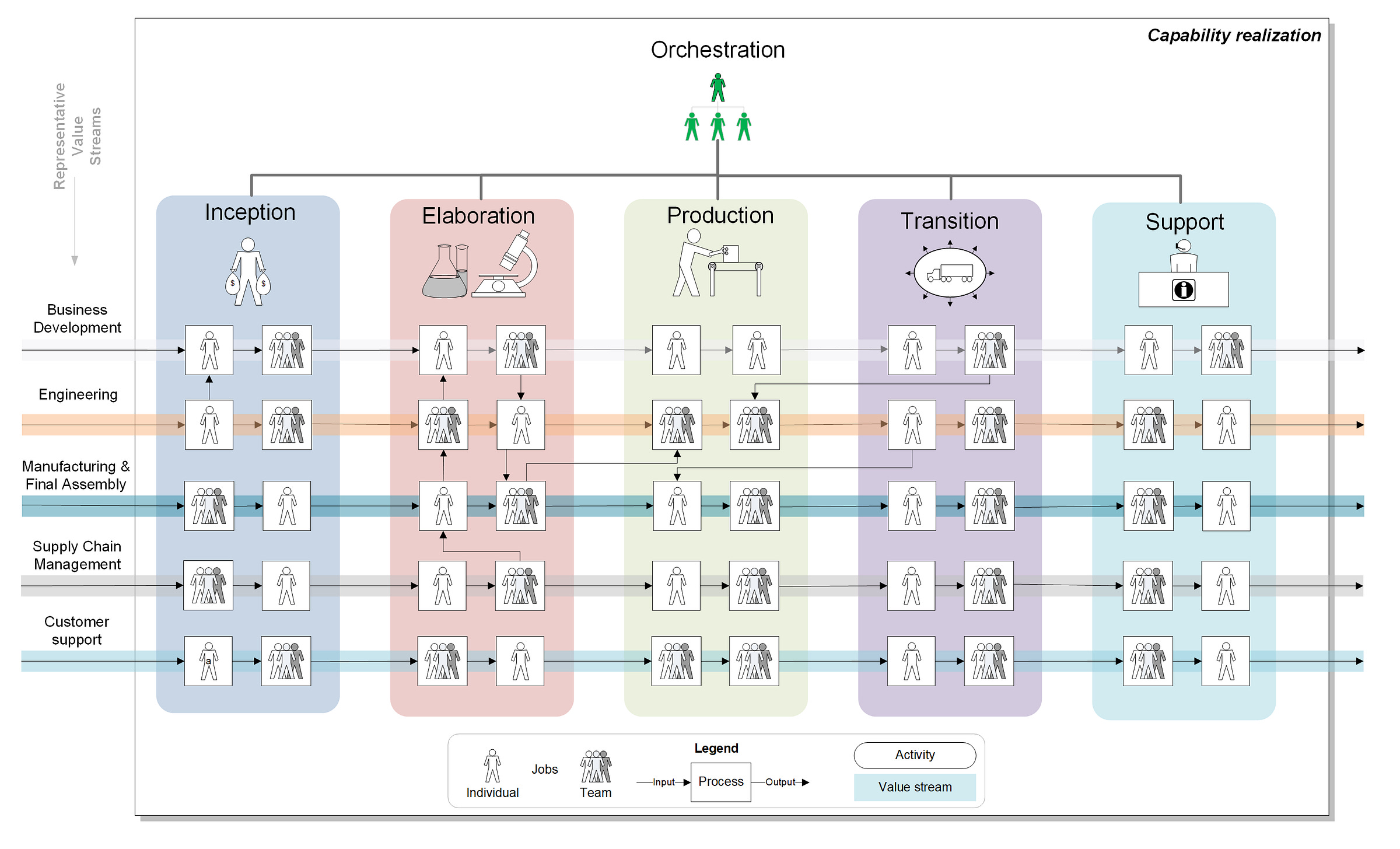

As organizations grow, complexity increases, making it difficult to balance short- and long-term priorities. The pressures of immediate survival often sharpen focus, but expanding teams, diversifying locations, and evolving work processes introduce challenges in coordination. Leadership often provides broad directives, but these simplified abstractions may not align with the specific tasks employees must execute. This ambiguity - along with shifting environments and incomplete handoffs from upstream teams - can cause confusion, misinterpretation, and inefficiencies. Without a well-integrated collection of processes spanning multiple dimensions, employees may struggle to apply the guidance they are expected to follow effectively, making work more complicated rather than streamlined.

Startups are understandably motivated by the necessities and uncertainties of survival through the endeavor’s next fiscal quarter. This pressure provides a focus for the workforce that improves attention on the most immediate priorities. But as an organization increases its size and diversifies its locations and work groups, and as the artifacts its members produce increase in complexity, teams find it much more difficult to strike a balance between short- and long-term perspectives, especially as evolutionary changes accumulate over extended periods of time. This is when efforts to document processes first emerge for young businesses.

Process guru John Stearman highlights the limitations of this approach when an established organization attempts to create a new product or service:

It was argued that in the same way a complicated tractor is built by parts, each performing only a simple task of horizontal, vertical, and circular motions, an organization could be created in such a manner that each person performed only a simple task. The mechanistic mode of organization was born as a logical extension of this conception and became instrumental in converting the army of unskilled agricultural laborers to semiskilled industrial workers. The impact of this simple notion of an organization was so great that in one generation it created a capacity to produce goods and services that surpassed the previous cumulative capacity of mankind. The essence of this mechanistic viewpoint of an organization is simple and elegant: an organization is a mindless system- it has no purpose of its own.

A socio-cultural view considers the organization a voluntary association of purposeful members who themselves manifest a choice of both ends and means. The critical variable here is purpose. In contrast to machines, in which integrating of the parts into a cohesive whole is a one-time proposition, for social organizations the problem of integration is a constant struggle and a continuous process.

The elements of mechanical systems are energy-bonded, but those of socio-cultural systems are information-bonded. The members of a socio-cultural organization are held together by one or more common objectives and collectively acceptable ways of pursuing them. The members share values that are embedded in their culture. The performance of each variable can be improved independently until the slack among them is used up. Then the perceived set of independent variables changes to a formidable set of interdependent variables. Improvement in one variable would come only at the expense of the others.

Adapting to new entrants or emerging technologies can also be such a challenge for any business. The need to allocate across these competing demands becomes progressively more challenging, as the number of dimensions that must be coordinated and organized to accomplish work increases. Organizations of any size are naturally chaotic, and the guidance provided by leadership is unfortunately often delivered in the form of simplified abstractions. These directions may not be relevant or helpful with respect to performing the work by the members of the responsible units and individuals in the organization. Because of this ambiguity, changing environments, and incomplete processing pushed out prematurely from upstream organizations, jobs become increasingly difficult to implement, and assignments may even be interpreted in contradictory ways. As a result, unless a coherent collection of processes is introduced that are well integrated across the many dimensions in which work must be performed, the direction which employees are instructed to follow may not be applicable to their situation.

Rummler and Brache call managing and deciphering this ambiguity "the white space" in an organization:

The greatest opportunities for performance improvement often lie in the functional interfaces - those points at which the baton... is being passed from one department to another... All too often, it's the organization chart, not the business, that's being managed... A primary contribution of a manager (at the second level or above) is to manage interfaces. The [functional] boxes already have managers; the senior manager adds value by managing the white space between the boxes.

Agents control, shape, and connecting processes within this white space, so it makes sense that they will also be the primary failure mode for these exchanges. This means that unless communications channels between communicating roles are explicitly designed, those responsible for acting on these exchanges are likely to adopt ad-hoc behaviors that are convenient for the circumstances and parties involved, rather than for achieving broader business objectives.

Even well-designed processes suffer when connected through these unpredictable and noisy communications channels. Just as in computer networks, the performance of these human-based communications channels is most likely to degrade significantly when under intense load. This arises when it is least convenient, such as when the business expands, undergoes adaptive change, or must respond to a crisis.

The connective tissue which joins the organization's separate units (people and information) operate as other information networks do, with implications to latency, congestion, failures, and mangled messages that networks must deal with in their design. An organization's leadership must serve as the master switch for this information system. A lesson from the book Master Switch, about the impacts of human operators in the early telephone network, is relevant here:

When human operators were needed to physically connect one phone line to another, a larger network meant a slower switching system, prone to bottlenecks and breakdowns.

In the ideal case - when the agents that are filling these gaps are competent, available, and motivated - the types of interactions may still not be appropriate to the situation and overload their capacity, which often complicates situations even more. As Tom DeMarco describes, some slack time is essential to investing for long-term improvement, and finding such slack may not be easy:

When companies and divisions and departments get themselves totally stuck, when they can't learn their way out of a paper bag, they often look to change the lines and boxes on the org chart. They'd be better off to concentrate on the space between those lines and boxes. Since healthy organizations use this white space as their learning center, you can bet that the nonlearners have got trouble exactly in the white space. Instead of being vital and collaborative, their white space is isolating and dangerous to explore.

Appropriate protocols are thus necessary for exchanging data and control information, managing synchronous and asynchronous operations, multiplexing unidirectional and bidirectional communications, and escalation when initiating or responding to high priority events. More interventionist techniques may also be required (packetization, compression, conversion, etc.) to improve overall throughput. Turning again to Rummler and Brache, they observe:

All organization structures have white space. The mission is not to eliminate white space. The mission is to minimize the extent to which white space impedes processes and to manage the white space that must exist.

While a well-designed structure can significantly facilitate improved organizational behaviors, when given enough time, tuning, and useful feedback, prioritization and load shedding of target business outcomes may be necessary, if the underlying expected communications breakdowns are to be systematically addressed. Any organizational structure that cannot eventually converge on these target outcomes, and adjust their own behaviors as these outcomes evolve, is not likely to achieve the competitiveness necessary for survival.