In the book Simplexity, Jeffrey Kluger points out that work is always more complex than it appears to be:

Just which jobs we consider complicated and which ones we consider elementary, even crude, is a judgment too often made not on the true nature of the work but on the things that attend it — the pay, the title, whether it’s performed in a factory or an office suite, in blue jeans or a gray suit. And while those are often reasonable yardsticks - a constitutional scholar may indeed move in a world of greater complexity than a factory worker - just as often, they’re misdirections, flawed cues that lead us to draw flawed conclusions about occupations we don’t truly understand. We continually ignore the true work people and companies do and are misled, again and again, by the rewards of that work and the nature of the place it is done.

It may not be much of a surprise that bosses and economic theorists don’t fully appreciate the complexity in many jobs. Both groups, after all, are interested mostly in performance, never mind how it’s achieved. More surprising is the fact that coworkers are often just as poorly informed about what the person one desk over or two spots down on the assembly line actually does all day. When they do give the matter any thought at all, they almost always conclude that the other person’s job is far less complicated than it is.

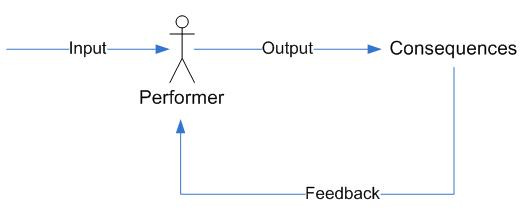

The longer it takes for this complexity to become apparent, the less useful this feedback will be in implementing changes that will have lasting effects on performance. People are motivated to change their behaviors when their own interests are connected to business needs. Causes must be connected to effects so they can make sense of information and how it relates to a particular context and framing of their work.

In The Principles of Product Development Flow, Don Reinertsen describes importance feedback plays in enabling teams to establish control over their environment:

Rapid feedback causes us to subconsciously associate our delivery of a work product and the beginning of the next process step. This attribution of causality gives us a sense of control, instead of making us feel we are the victim of a massive bureaucratic system.

In the book Improving Performance, Brache and Rummler describe the factors which affect the ability to perform work. Collectively, these factors determine the extent to which planned work can be successfully executed and determine the extent to which the means of performing such work can be improved over time. These factors include:

Job Preconditions

Are the inputs accessible and suitable for processing?

Can the task be performed without interference?

Are the procedures and workflow logical?

Is help available if required?

Performance specifications

Do job standards exist?

Are they attainable?

Are they accepted by the people who must perform the work?

Ability to execute

Are the roles that individuals are assigned to perform consistent with their experience and preparation?

Are the responsibilities for that role understood and accepted?

Do the performers have sufficient capacity available to implement these roles within the time allocated?

Feedback

Will feedback information be relevant, accurate, specific, understandable, and timely?

Will the feedback be provided in a way that is useful to the performer and so that adjustments can be incorporated within the required period of performance?

Motivation

Have incentives and consequences been established to support desired performance?

Are the criteria for reporting progress and estimates of remaining work well designed, agreed to, and appropriate to the situation?

Jobs are 'actionable' if and only if they satisfy all the above attributes. When some portion of a work package does not satisfy these attributes, the time it will take to perform that work will be more variable, since work products that will be produced will be more likely to have less utility than desired, and risks associated with achieving target outcomes will be increased.

Teams select the most actionable work from a work package to perform first, even though this work may not be the most important work from the perspective of the customer; while it may enhance the team's ability to demonstrate progress in the short term, this approach may not give the best long-term result. Simply put, the degree to which work is actionable determines the pace at which work can be acted on, and the extent to which rework can be avoided.