James Grier Miller was a pioneer in systems science and complex adaptive systems. His book, Living Systems, provides a clarity of thought and expression that is missing in more modern treatments of these topics. His work laid the foundation for what came to be known as the living systems theory. He explores this subject to a humbling depth, with over one thousand pages typeset in a textbook so thick and in a font so small this reader cries out for a Kindle version (sadly unavailable). Alternatively, the book is online through the link above.

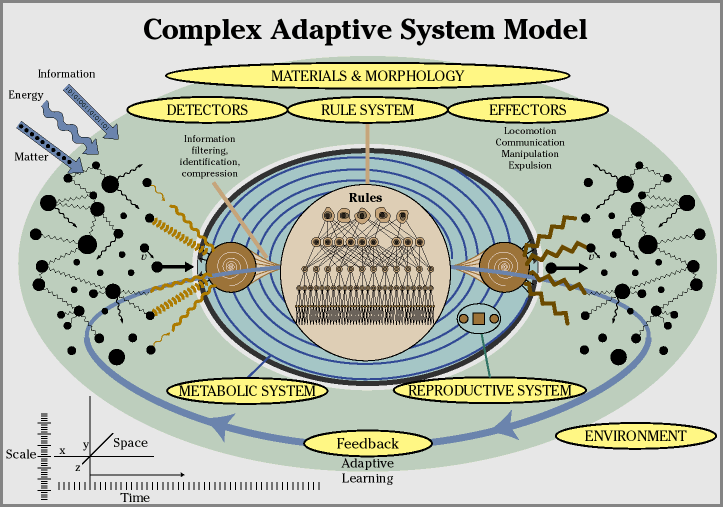

Miller argues that living systems exist at eight nested hierarchical levels, not unlike matryoshka dolls. These levels begin at the cellular level and build into organs, organisms, groups, organizations, communities, societies, and supranational systems. Miller argues that each of these levels can be studied from a common viewpoint, that of nineteen comparable subsystems which each interact within their enclosing and subordinate structure to form a holistic system, as Figure 1 depicts. Each of these subsystems operates within a context which is appropriate to the level of the system. Collectively, all achieve transformations of space and time, matter, energy or information, performing functions such as locomotion, manipulation, communications, and expulsion.

Regardless of scale, state, or perspective, these living systems have both form and function and have properties that can be observed and categorized. As these patterns are recognized and decomposed, a foundation for reasoning can be formed on topics such as the best possible arrangement and provisioning of parts for achieving some purpose. To pursue this purpose, each entity must make effective choices from real options available to influence its future, given a set of initial conditions, so that beneficial emergent properties can unfold across space, scale, and time.

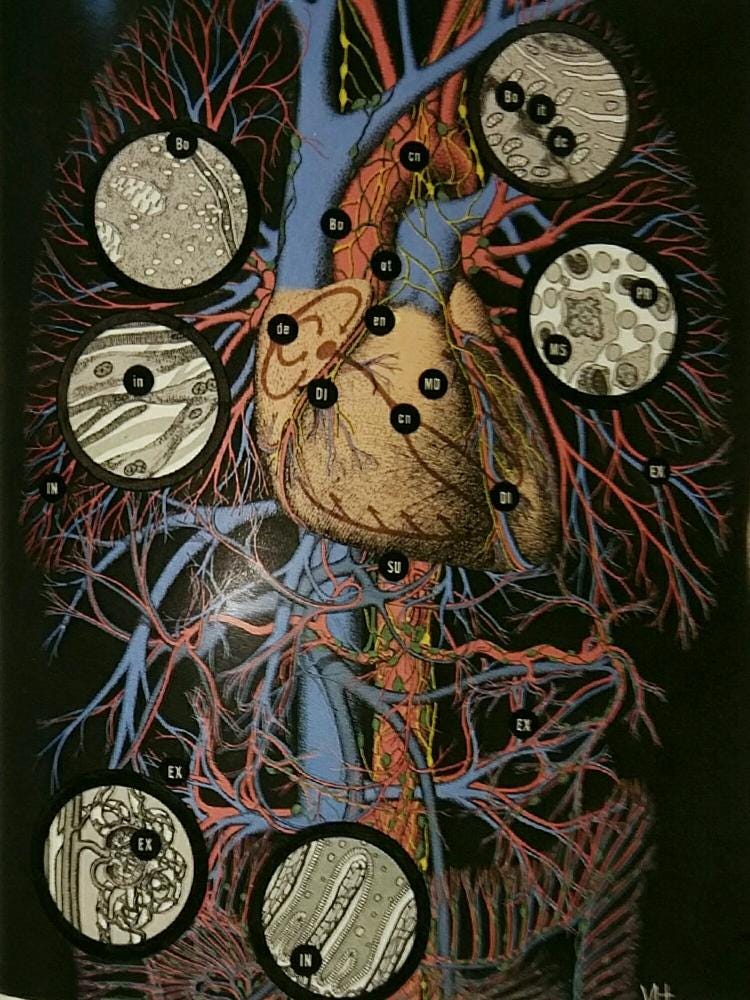

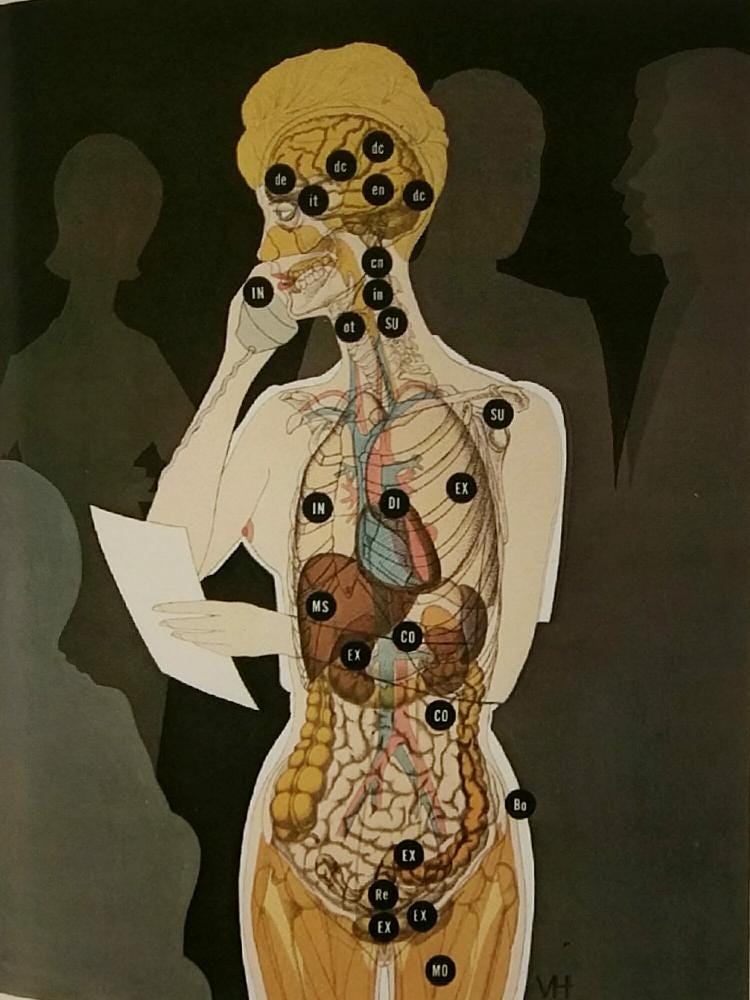

He drills into each of these subsystems as both a categorization scheme (or logical architecture) and with a specialist's love of details, revealing both the structure and processes of each subsystem. He also goes to a great deal of effort to explain key characteristics of these patterns across all levels; for example, he devotes one whole chapter (of eighty pages) to the topic of information overload, a topic essential to understanding the forces and constraints at play. He also provides a full-color plate in which he points out common characteristics of these subsystems within the level being studied (three are depicted below).

An Organ

An Organism

An Organization

Highlights

3. Subsystems

3.1 Subsystems which process both matter-energy and information

3.1.1 Reproducer

3.1.2 Boundary

3.2 Subsystems which process matter-energy

3.2.1 Ingestor

3.2.2 Distributor

3.2.3 Converter

3.2.4 Producer

3.2.5 Matter-energy storage

3.2.6 Extruder

3.2.7 Motor

3.2.8 Supporter3.3 Subsystems which process information

3.3.1 Input transducer

3.3.2 Internal transducer

3,3,3 Channel and net

3.3.4 Decoder

3.3.5 Associator

3.3.6 Memory

3.3.7 Decider

3.3.8 Encoder

3.3.9 Output transducer

4. Relationships among subsystems or components4.1 Structural relationships

4.1.1 Containment

4.1.2 Number

4.1.3 Order

4.1.4 Position

4.1.5 Direction

4.1.6 Size

4.1.7 Pattern

4.1.8 Density

4.2 Process relationships

4.2.1 Temporal relationships

4.2.1.1 Containment in time

4.2.1.2 Number in time

4.2.1.3 Order in time

4.2.1.4 Position in time

4.2.1.5 Direction in time

4.2.1.6 Duration

4.2.1.7 Pattern in time

4.2.2 Spatial-temporal relationships

4.2.2.1 Action

4.2.2.2 Communication

4.2.2.3 Direction of action

4.2.2.4 Pattern of action

4.2.2.5 Entering or leaving containment

4.3 Relationships among subsystems or components which involve meaning

5. System processes

5.1 Process relationships between inputs and outputsMatter-energy inputs related to matter-energy outputs

Matter-energy inputs related to information outputs

Information inputs related to matter-energy outputs

Information inputs related to information outputs

5.2 Adjustment processes among subsystems or components, used to maintain stability

5.2.1 Matter-energy input processes

5.2.2 Information input processes

5.2.3 Matter-energy internal processes

5.2.4 Information internal processes

5.2.5 Matter-energy output processes

5.2.6 Information output processes

5.2.7 Feedback

5.3 Evolution - Emergence, growth, cohesiveness, and integration5.5 Pathology

Lack of matter-energy inputs

Excesses of matter-energy inputs

Inputs of inappropriate forms of matter:energy

Lack of information inputs

Excesses of information inputs

Inputs of maladaptive genetic information in the template

Abnormalities in internal matter processes

Abnormalities in internal information processes

5.6 Decay and termination

As system engineers are prone to say, the rest is just details, though that would be missing Miller's point. His conclusions emphasize (especially at the level of supranational systems), that it is far better to recognize such patterns and deal with them proactively than to wait until decay and termination set in. This insight relates to our responses to threats such as cybersecurity and related changes in our current social, technological, and political environment, though only if the mitigations are appropriate, timely, and effective.