Navigating chaotic frontiers

Out of clutter, find simplicity. From discord, find harmony. In the middle of difficulty lies opportunity. - Albert Einstein

Where innovation meets inertia, chaos isn’t just a threat - it’s the landscape. Navigating complex systems isn’t about taming the noise; it’s about interpreting it. In complex systems, the noise isn’t something to eliminate; it’s something to decode. For leaders aiming to drive progress across turbulent environments, success depends less on certainty and more on the courage to make decisions where no perfect clarity exists. Between early adopters and the mainstream, between clarity and confusion, lies a landscape full of friction and potential. What should your goal be? To make progress when every map is incomplete.

Wrestling with needs

Defining the needs of a diverse stakeholder landscape feels less like a strategy session and more like wrestling pigs: exhausting, messy, and vaguely entertaining to those on the sidelines. Every stakeholder brings unique goals, constraints, and expectations, woven into a knot of competing demands. Untangling this tangle requires more than listening - it requires synthesis.

Crossing the Chasm - and then?

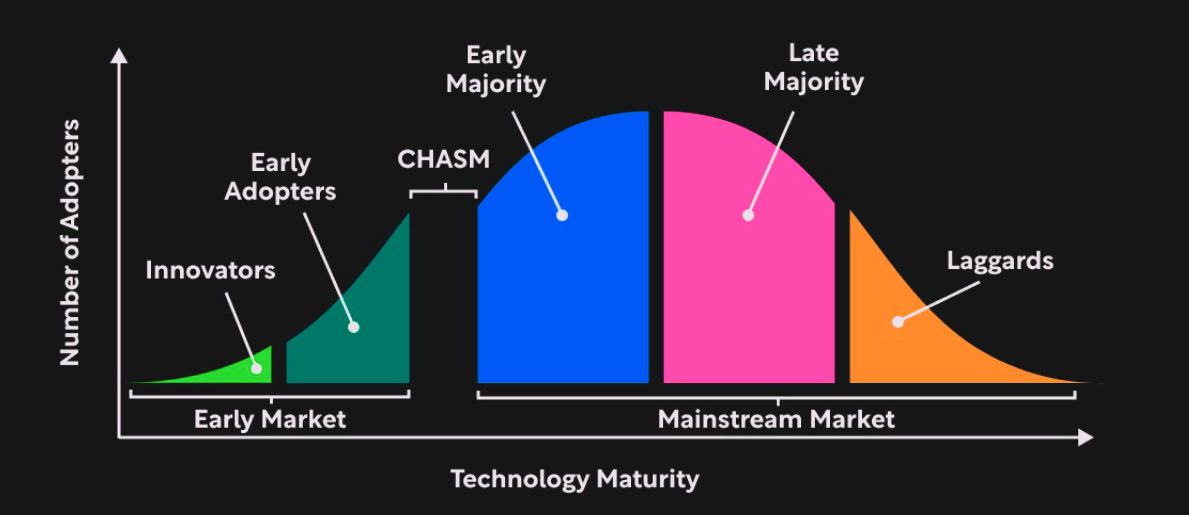

Geoffrey Moore’s “chasm” (figure 2) remains a harsh terrain between early adopters and the mainstream. Where early adopters chase novelty and technical credibility, the mainstream seeks stability and proven value. Bridging this divide demands more than marketing finesse—it requires frameworks like Ivar Jacobson’s Essence to map the hidden gaps in value perception. The irony: your solution must be credible to gain users but only gains credibility through use.

Agreement is not understanding

It’s tempting to think that group consensus means shared understanding. But the pressure of collaboration often creates premature convergence - where teams subtly collapse problem and solution spaces into one fuzzy middle. The result? An illusion of alignment that quietly erodes design integrity.

To truly define the problem, one-on-one conversations often reveal buried needs. In group dynamics, though, the process accelerates toward comfort rather than clarity. We declare victory too early. We move forward before we're ready.

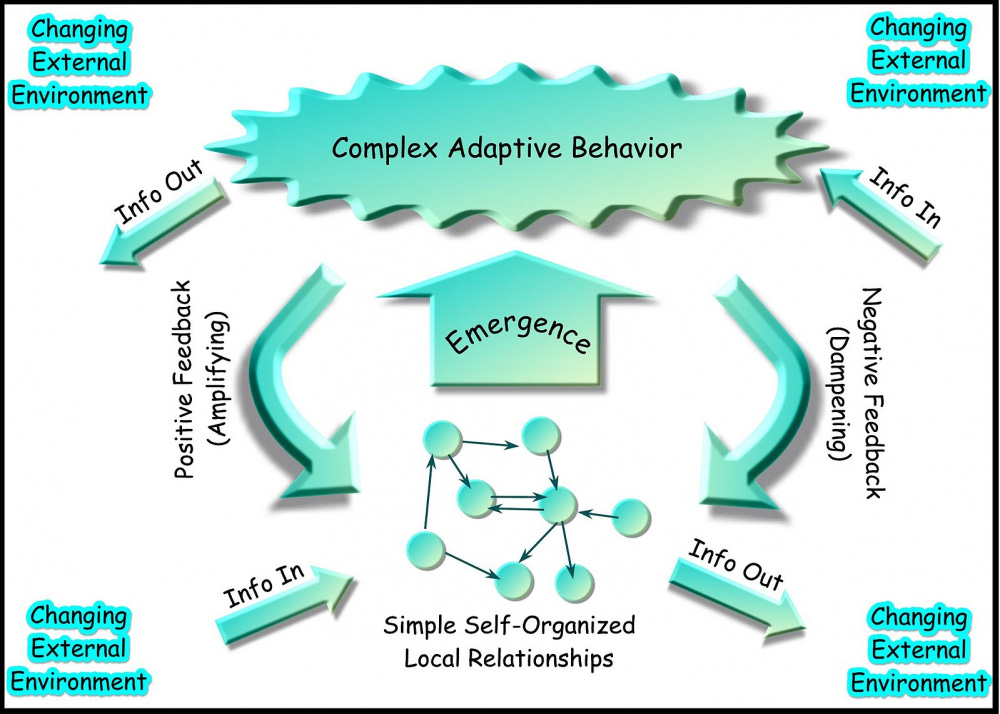

The challenge of harmonizing the pursuits of local relationships with the broader interests of the collective - so that progress can emerge in the complex, adaptive behavior (see figure 4) - requires harvesting the feedback available from explorations, relevant evaluations, and experiences drawn from prior transformations. Exploration, evaluation, and iteration are not luxuries in these environments—they’re essential. The “answer” doesn’t live in a static blueprint. It emerges through disciplined cycles of feedback and reframing.

Patterns in the noise as opportunities for learning

John Sterman, in his book Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World, further illuminates how these dynamics unfold:

Much of the information we receive is ambiguous. Ambiguity arises because changes in the state of the system resulting from our own decisions are confounded with simultaneous changes in a host of other variables. The number of variables that might affect the system vastly overwhelms the data available to rule out alternative theories and competing interpretations.

This identification problem plagues both qualitative and quantitative approaches. In the qualitative realm, ambiguity arises form the ability of language to support multiple meanings… Rich, ambiguous texts, with multiple layers of meaning, often make for beautiful and profound art, along with employment for literary critics, but also make it hard to know the minds of others, rule out competing hypotheses, and evaluate the impact of our past actions so we can decide how to act in the future.

Sterman goes on to describe other challenges in balancing between the needs of the few (but potentially powerful) and the many:

To influence the actors in our transactional environment we have to understand why they do what they do. Understanding is different from both information and knowledge. Information deals with the "what?" question, knowledge with the "how?" question, and understanding with the "why?" question... The why question is the matter of purpose, that of choice. And the choice is the product of the interactions among the three dimensions: rational, emotional, and cultural. Rational choice is the domain of self-interest, or the interest of the decision-maker, not the observer. A rational choice is not necessarily a wise choice. It reflects only the perceived interest of the decision-maker at the time. Meanwhile, wisdom has ethical implications and considers the consequences of an action in the context of a collectivite.

Progress in adaptive systems looks less like marching in formation and more like dancing with feedback. Sterman’s system dynamics remind us: decisions shape results which reshape understanding. Ambiguity isn’t an obstacle—it’s where learning happens.

The Wicked Webs We Weave

Horst Rittel first described the challenges of such chaotic environments on large projects in a paper on Dilemmas in a general theory of planning back in 1973. He made these observations about such situations:

There is no definitive statement of the problem - it's an ill-structured, evolving set of interlocking issues and constraints (a tangled mess of problems)

No one person understands the problem sufficiently

Since the problem lacks definition, so does the solution. The implications are that the problem-solving process ends when resources - such as time, money, or energy - are exhausted, rather than when an intended solution emerges.

Each fragment of a solution concept exposes new aspects of the problem, requiring further adjustments to other aspects of the solution.

Without a full set of requirements to establish context, tradeoffs across solution contexts are not possible; one cannot first understand, then solve.

Solutions are neither right nor wrong. They might be better or worse, but what's good enough for one party may not be good enough for another

Analysis is considered procrastination by those in power, and one opinion is believed as good as another

Rittel named the combination of these factors in situations 'wicked problems' because they involve the interaction of many dynamic forces which amplify the effect that each factor would produce on their own:

Solution abstractions, the fuzzy, shape-changing lingua franca by which participants attempt to communicate and justify tangible aspects of an unfolding environment over time

Fragmentation, which emerges from the above tensions and forces, works against achieving solution cohesion, and erodes the primary motivation for achieving architectural integrity

Social complexity, which arises from the diversity of stakeholders, who all expect to buy into each recommendation, and who want to avoid having to change themselves

As Rittel and Webber warned, wicked problems don’t have tidy definitions or fixed endpoints. Each attempted solution refracts the problem in new ways. There are no final victories—only more refined approximations.

And in the absence of certainty, power dynamics fill the gap. Data becomes secondary to opinion. Decisions feel like tradeoffs between competing partial truths.

Designing the Compass

So how do we lead through this? By building decision-making structures that aren’t stability-bound but instead enable strategic shifts. These pathways must translate messy feedback into structured decision-making, providing a consistent “North Star” even as the landscape keeps shifting. Such tools don’t eliminate chaos, but they help navigate it with intentions guiding the necessary refinement of ambiguity and thereby making it actionable.

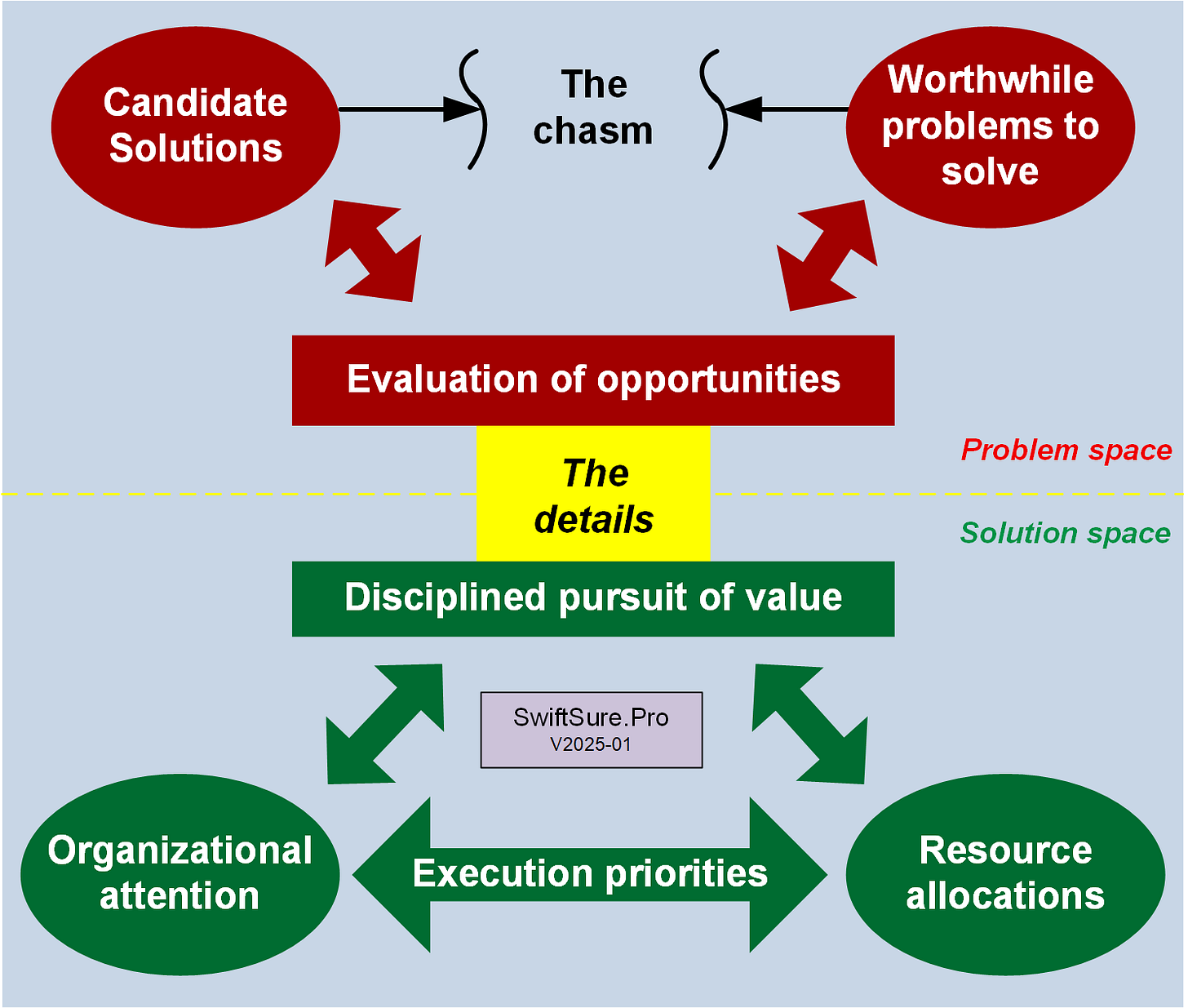

Restructuring decision-making

A disciplined, opportunity-driven approach is essential to confronting such situations. Projects must learn to consistently evaluate solution concepts and connect them to the underlying values and needs of the business overall. Endeavors must then properly allocate precious resources across projects to maximize returns. Until they develop this competency, values and goals will remain mere abstractions, rather than foundations for strategic clarity. Clarity is earned—not given. Strategy isn’t just about choosing a path—it’s about choosing the right conversations to have. And that begins by asking better questions.

A well-designed decision-making framework is necessary to provide stability for decision agents in their actions and considerations. If your team keeps circling the same confusion, if your strategy feels more like camouflage than clarity—it may be time to upgrade the frame, not just the tactics.

Confronting ignorance

It is necessary to confront, rather than ignore, uncertainty. The unfortunate alternative, as George Bernard Shaw warns, relies on false hope:

Ignorance is a most wonderful thing. It facilitates magic. It allows the masses to be led. It provides answers when there are none. It allows happiness in the presence of danger. All this while, the pursuit of knowledge can only destroy the illusion. Is it any wonder mankind chooses ignorance?

Magic may feel comforting. But in the end, only understanding makes progress real.

Let’s move beyond the illusion of certainty—and into the opportunities available by choosing more wisely.