Realizing strategic objectives

People in any organization are always attached to the obsolete—the things that should have worked but did not, the things that once were productive and no longer are - Peter Drucker

To avoid oversubscribing to obsolete ideas, endeavors must evaluate the relative merit of alternative future approaches, investments, and product lines; integrate this information across many time horizons, environments, and operational scenarios; and mobilize the necessary resources to successfully place these changes into broad usage. To do this effectively, multiple factors must be considered:

the benefits and risks achievable from investing in new or modified capabilities

the period in which these enhanced capabilities could be made available

the availability of situations to which such capabilities could be applied to

the uncertainty implicit in pursuing these courses of action

the level to which primary and affected parties understand, are willing to accept, and will personally support the changes required

to whom the benefits are expected to accrue, and how the accounting of costs and benefits associated with transitions will be reconciled over time

A study of these factors and their interactions can illuminate consideration of all opportunities and their impact on strategic objectives. Without an adequate understanding of these dynamics, the strategic plans of a business can get lost in the daily grind of reviewing opportunities, reporting status, managing risks, and enforcing operational discipline.

The focus on longer-term benefits may be sharpened by adopting an organizing framework such as that provided by program management, though such frameworks cannot achieve effective change by incentives, decree, or force of personality alone. In The Guide to Lean Enablers for Managing Engineering Programs, a Joint Community of Practice on Lean Program Management between MIT, PMI, and INCOSE, programs are defined as follows:

A program is a group of related projects, subprograms, and program activities managed in a coordinated way to obtain benefits not available from managing them individually... Programs deliver benefits to organizations by generating business value, enhancing current capabilities, or developing new capabilities for the organization, customers, or stakeholders. A benefit is an outcome of actions, behaviors, products, systems, or services that provide utility to the sponsoring organization as well as to the program’s intended beneficiaries or audience.

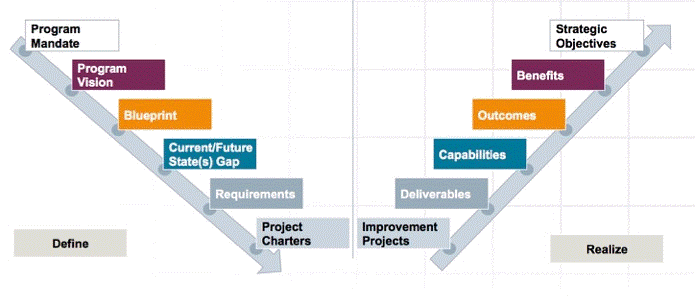

Effective engineering depends upon focused exploration and probing of candidate solution elements, typically in time-boxed endeavors, while navigating within an unfamiliar territory. Progress may be accomplished by executing iterative, overlapping phases of Definition and Realization, as depicted in figure 1. Either explicitly or indirectly, the activities in each of these groupings set the context for those in the other grouping in an iterative and recursive fashion.

In a paper on Benefits Management for such endeavors, John Sopko highlights the differences in pursuing benefits for a program and outcomes for a project:

When one discusses the difference between projects and programs, the answer can be found simply by examining the expected results by which the success of each is measured. Projects are deemed successful if they produce the desired deliverables at the desired time and on budget. Programs have expectations beyond project deliverables and focus on how these deliverables are applied to realize benefits. In the end, a program’s success is measured against the effectiveness of which they deliver benefits. Programs are the mechanisms through which benefits are defined, planned and realized by organizations... a benefit is an outcome of actions or behaviors that provide utility, value, or a positive change to the intended recipient.

Figure 1 maps the high-level activities of program phases onto the V-model of systems engineering as rendered by the Project Management Institute. The ways and means necessary to accomplish these definition and realization activities must be incrementally matured, so they both can be performed consistently and concurrently. Unfortunately, the yield from available investments is often sufficiently far in the future that its results are uncertain, potentially disappointing investors, labor, and management alike. One of the primary reasons for such disappointments is that optimists tend to overestimate gains and underestimate loses, while pessimists suffer from the opposite bias. A dilemma thus can arise despite attempts to negotiate a middle course, since the promise of long-term benefits may need to be sacrificed at the altar of necessary short-term gains.

Like projects, programs require an early focus on eliciting stakeholder needs and synthesizing a shared vision worthy of both types of investments. Meanwhile, everyone goes forward with the hope that things will improve with time, and the belief that they share a consistent interpretation of this context. Aids like blueprints are essential for moving forward. Yet such ‘definitions’, as they are, typically abstract and unproven, are often based upon mental models with different underlying assumptions. This will only be reconciled through appropriate investments in mutual understanding, negotiation, and alignment, all of which require time.

In the absence of such investments, conceptual ambiguity can be exploited as cover for entrenched but favored positions adopted by those in power, delaying the ability to focus on what is in everyone's better interests and their potential future gains. Evangelists often dangle the appealing idea that investments will pay their own way and much more, despite the need to somehow hurdle the uncertainties.

Once a shared vision is sufficiently captured, clarified, and embraced, blueprints of adequate fidelity can be defined and used to explore which interventions will shift the needle of measurable progress in an acceptable direction. The resulting focus will produce increased confidence that further investments will deliver increased value even in a landscape of shifting technological and mission evolution, a goal that any healthy business entity must demonstrate periodically.

To demonstrate that necessary outcomes can indeed be accomplished within acceptable levels of confidence, endeavors must learn to:

survey the environments from sufficient viewpoints for the systems of interest and the purposes being pursued

analyze the gaps between existing capabilities and those required to achieve the benefits across these contexts

translate these gaps into the statements of work necessary to realize these complementary capabilities, despite the uncertainties creeping in over multiple business planning cycles, and with inherent affordability constraints.

As their means of production matures, teams can begin to learn how to shape - and even model - the definition of these capabilities, and their realization - by crafting configuration definitions and specifications which can be elaborated into deliverables. All of this must of course be achievable within realistic constraints of time, talent, and resources.

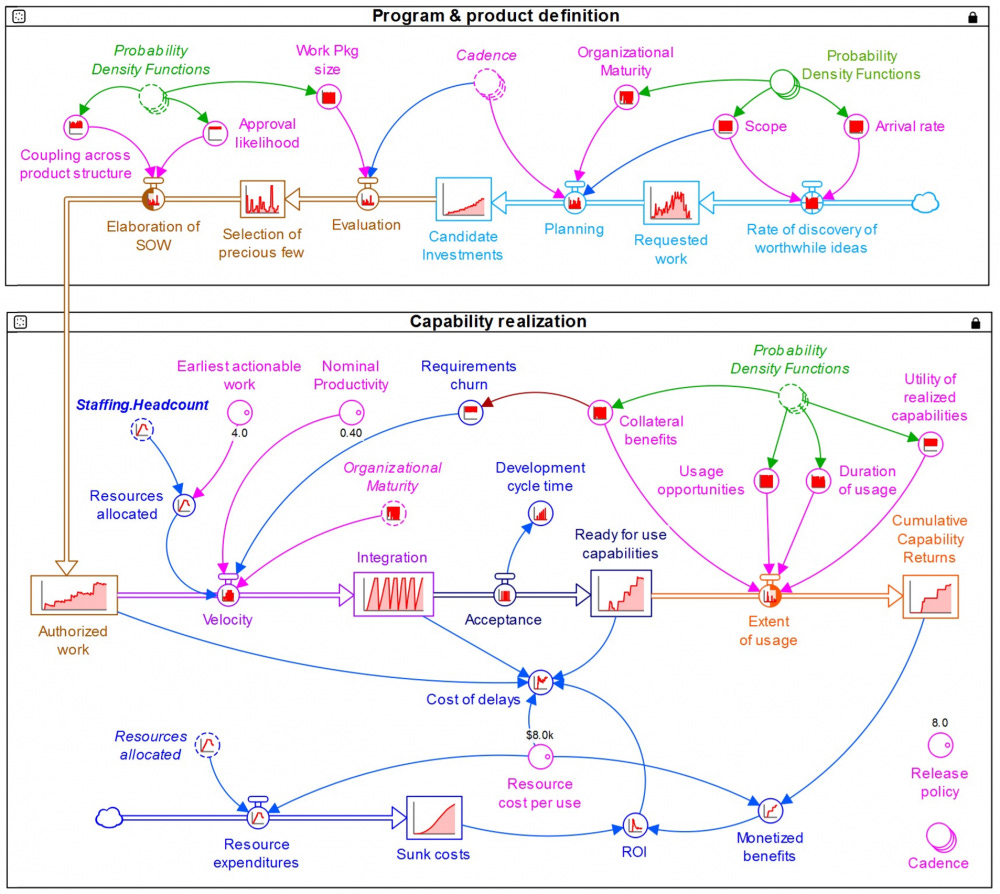

We can visualize these dynamics and related constraints by considering how this uncertainty influences the progressive delivery of value by a system. Figure 2 depicts the end-to-end flow from ‘lust to dust’, i.e. from ideas to the time-value accumulation of benefits realized, influenced by a representative set of factors (shown as circles) and boxes (depicted as stocks) over time. This diagram reflects the structure of a simulation of this flow described in more detail in this post.

Such a model allows the capacity, throughput, and returns from this flow to be evaluated across different operating scenarios.

What to do in the face of such uncertainty? Programs, out of necessity, must learn to improve their constituent project outcomes and sniff out dry wells sooner, rather than later. This capability requires a closed-loop control system that can quickly weed out unnecessary variation in bottom-line results while amplifying worthwhile investments in high leverage opportunities. The goals of investments in major new capabilities should be to achieve architecture clarity and feasibility early, while maximizing the potential for achieving target outcomes expected in pursuit of practice, discipline, and learning.

The raw material for this evolution is ideas. These ideas may be cheap to propose, and quite expensive to evaluate, justify, and pursue; clearly, an effective selection process is necessary to organize the corresponding decisions. The patience and temperament of those in charge of these filters may introduce further bias and instability into the pursuit of important target outcomes and can result in resource allocations being suboptimal. These evaluations rely upon a coarse-grained analysis of the relative merit of each idea, with credible projections of necessary resources to create and sustain them over their lifecycle.

Each chosen opportunity requires careful consideration of the minimum viable features worthy of investment, along with a sequencing of the order in which these features should be built. Once the most promising of these ideas have been selected, the work to implement them must be adequately planned and competently executed. Yet benefits from this work will only be realized when they can be made available within the operational opportunities for application of these capabilities and used in ways that achieve the sought-after benefits.

Since limits to growth inevitably constrain the opportunities that can be pursued at any one time, candidate solutions must be carefully evaluated; none may be achievable without fresh thinking, strategic scoping, and deliberate pivots to cultural norms. Each gambler making such bets observes their hands and their competition's plays through their own lenses of knowledge, experience, and exposure to risk. Each play requires eyes wide open watching for circumstances to trigger the need to call or fold.

Projects are bundles of bets on such ideas. In turn, portfolios are bundles of these projects and may be less susceptible to streaks of luck when the aggregation elements are complementary and align with the stars. Investments in each bet require courage given the incomplete knowledge and uncertain future they must confront, and discipline to reduce the collective dependence on this luck.

Building on first principles and notable prior accomplishments is thus a more effective strategy than wishful thinking; the latter is the behavior of a gambler, not a trustworthy custodian of talent and treasure.