Seek first to understand

I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand. - Confucius

Understanding isn’t a courtesy - it’s a craft. To act wisely in complex environments, we must first explore what others see, believe, and know. Listening with intention isn’t passive; it’s the first form of agency.

One of Steven Covey's Seven Habits is to 'Seek first to understand, and then to be understood.' Action without understanding will inject chaos, not reduce it. But achieving an understanding of any topic requires us to probe much deeper until we have considered and accepted the viewpoints of all parties for the presenting circumstances.

We must engage with intellectual precision—diagnosing situations, surfacing constraints, and grounding our actions in relevant knowledge. Only then can better outcomes emerge from informed choices.

The roots of understanding

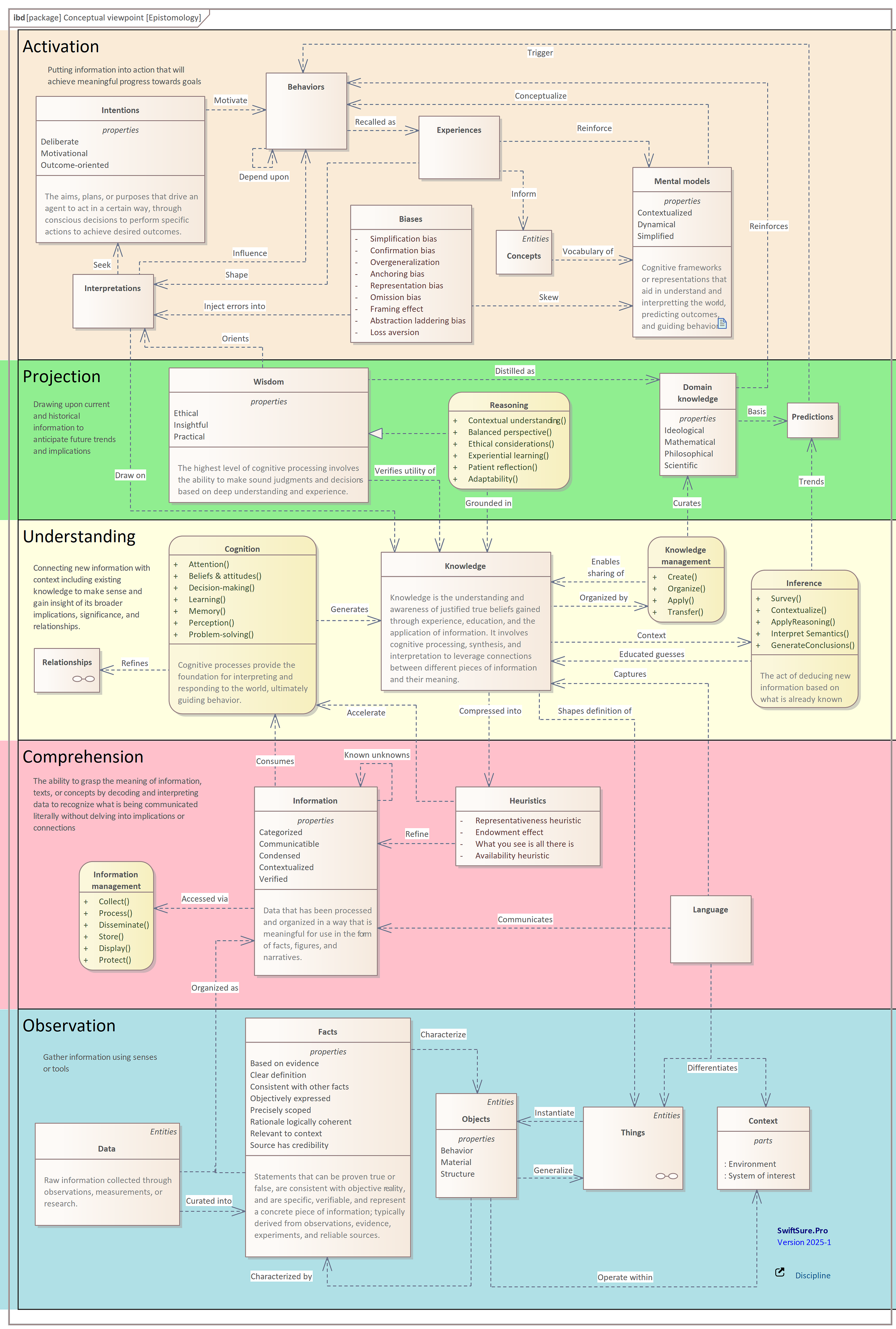

Epistomology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. According to Agnes Callard, knowledge is simply the name for an answer that is the product of a completed inquiry into a question. As Figure 1 indicates, it connects observations with meaning and draws on knowledge to navigate through courses of action.

This makes understanding a prerequisite for effective action. Actions to build understanding are exploratory probes into chaos, a necessity chock full of learning opportunities. And understanding is subject to many influences that may skew interpretations and contaminate behaviors, especially when coordination is required.

Understanding, acceptance, and support

When such understanding is required across a diverse community of practitioners, rather than just from a few selected individuals, it becomes more difficult to dictate that they adopt proper behaviors. Culture rules. Each member of culture brings their own expectations, beliefs, ceremonies, and traditions which they have adopted through their experiences. No amount of explanatory power is likely to win them over from that viewpoint. Callard again: “… you learn what you really understand, and what you only appeared to yourself to understand, when you put your supposed knowledge to the test by trying to explain it to someone.”

Inevitably, in navigating this terrain, tensions reveal themselves through competing cycles of:

scope-driven investment decision allocating resources among competing demands:

iterative, time-boxed activities producing viable work products

cultural responses to learning opportunities shaped by the perceived fitness of the endeavor

responsively adapting to shifting environments

Without adaptive control tied to first principles, performance may oscillate painfully - especially in periods of decline. Yet even then, outsized rewards remain possible, albeit at the cost of tough decisions and daring commitments.

Yet even in decline, big rewards are still possible, though achieving them will require commensurately painful decisions, actions, and risks. These factors amplify the cone of uncertainty around target outcomes that waxes and wanes in two separate waves. The first results from individual engineering and construction projects of any meaningful size and complexity. There will inevitably be winners and losers that result from these decisions. Yet inevitably, the routes over which future value can be accessed must be concentrated for growth to be economically viable. Arthur M. Wellington eloquently described the challenges of such decisions in his classic 1887 work, The Economic Theory of the Location of Railroads:

The correct solution of any problem depends primarily on a true understanding of what the problem really is, and wherein lies its difficulty. We may profitably pause upon the threshold of our subject to consider first, in a more general way, its real nature: the causes which impede sound practice; the conditions on which success or failure depends; the directions in which error is most to be feared. Thus we shall attain that great perspective for success in any work a clear mental perspective, saving us from confusing the obvious with the important, and the obscure and remote with the unimportant.

Wellington's focus on outcomes, constraints, priorities, and risks requires understanding the concepts of operations for the domains of interest. Immanuel Kant described the power of abstractions in laying a foundation for such understanding:

In order to make our mental images into concepts, one must thus be able to compare, reflect, and abstract, for these three logical operations of the understanding are essential and general conditions of generating any concept whatever. For example, I see a fir, a willow, and a linden. In firstly comparing these objects, I notice that they are different from one another in respect of trunk, branches, leaves, and the like; further, however, I reflect only on what they have in common, the trunk, the branches, the leaves themselves, and abstract from their size, shape, and so forth; thus I gain a concept of a tree.

Abstractions and pattern recognition are innately linked. Generalizations of properties help us systematically develop and verify hypotheses of the connections between causes and effects. Unfortunately, these generalizations may not serve us by recognizing points of light as distant galaxies, rather than as asterisms that fit well with our popular narratives. Distractions abound, ideas are cheap, hindsight is biased, and information needed for proper decision-making may often be inaccurate or just plain unavailable.

Visionary early adopters need more than platitudes and good attitudes, especially when skeptics resist advice that is contrary to their traditions. In cultures of high resistance, change agents are grossly outnumbered. Stakeholders who are under pressure are more likely to fall back on historical patterns, even after they are no longer acceptable. Those behaviors have built their reputation and world view within their community. To satisfy the expectations of some new role, these actors must understand and accept the new actions they will be responsible for, and support the necessary interfaces with others, so improved outcomes can be achieved. Unfortunately, when reality is viewed through their lenses, causes and effects are often disconnected in time from context.

Incentives for faking it

Often leaders are infected by reality distortion fields or magical thinking. Instead, leadership must shape the environment in which the communities making up this culture operate and provide them with the necessary ingredients for change. Change agents can then define a set of objective criteria by which success will be measured and facilitate charting a course towards satisfying those criteria, and their realization, consistent with an elaboration likelihood model. Their collective beliefs may be logically inconsistent with rational analysis; nevertheless, those assigned to new roles must embrace their responsibilities and agree to support each other in making the necessary transformations. Hopefully, these require steps, rather than leaps, of faith.

In his book Balancing Agility and Discipline, Barry Boehm describes the underlying root causes of such uncertainty:

ambiguity about the nature of the problem(s) that should be addressed

risks about the implementation of candidate solutions

unreconciled misunderstandings and flawed assumptions

unknowns about what options will be available in the future, and what environment they should be evaluated within

Though this uncertainty is often masked, projects may be not much more than a bundle of ideas that have attracted the attention of decision authorities. They may choose a fork in the road after trying other options and discovering they did not adequately understand the future they were getting themselves into. In such situations, the information will always be incomplete, and decisions will always be temporary. The causal chain between desirable effects and underlying upstream decisions may not be immediately apparent, even when the facts are known. Projects are always having changes in leadership, structure, or available resources. The longer the projects are, the greater the number of events that must be successful, and the more likely it will be that gaps in performance will creep in.

Sponsors usually must choose from many different potential investment opportunities, each promising predictability and clamoring for precious resources, and presuming that all resources are interchangeable and offer similar value creation over the long term. To minimize their exposure to Parkinson's law, leaders strive to bound these sources of uncertainty, striving to achieve as predictable a set of outcomes as possible. If project outcomes were indeed normally distributed in such portfolios, it would be possible to dial in historical data and the risk tolerance sponsors were willing to absorb. But individual project outcomes are more likely to follow heavy-tailed distributions, with many underlying causes, from sparse or unreliable historical data to unfamiliar execution environments.

Oversimplification of reality

A further complication arises when this uncertainty arises when a common set of root causes are threaded through multiple projects in a portfolio. These root causes form a common failure mode across these projects that can be self-reinforcing. As an example, stakeholder's mental models inevitably are simplifications of the diverse realities in which projects must be executed. Ideally, the highs and lows of this uncertainty would be offsetting. Steve McConnell believes that teams are more likely to commit to more than they can deliver because people have an innate desire to please. The laws of physics and lessons of history are inevitably stronger than the enthusiasm of change agents and the ambitions of project advocates. Yet unless such underlying root causes for failures can be recognized and confronted, these failure modes are likely to amplify the underlying uncertainty that typically emerges individual projects themselves.

This over-simplification is an essential property of environments that are exposed to changing circumstances. Even though problems, concepts, or ideas have been embraced by stakeholders, their actual definition may not be actionable despite prior commitments to action. In these situations, each stakeholder may have their own mental models of what these abstractions mean and are likely to each adopt the interpretation most useful to them or their organizations. The systems' implications of these models may not be apparent.

Phillip Tetlock, author of the book Superforecasting, provides us with a disturbing example of the fuzziness of the lines we draw between which emerging conditions are significant and which can be overlooked:

In March 1951 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) 29-51 was published.? "Although it is impossible to determine which course of action the Kremlin is likely to adopt," the report concluded, "we believe that the extent of [Eastern European] military and propaganda preparations indicate that an attack on Yugoslavia in 1951 should be considered a serious possibility." ...

But a few days later, [Sherman] Kent was chatting with a senior State Department official who casually asked, "By the way, what did you people mean by the expression 'serious possibility'? What kind of odds did you have in mind?" Kent said he was pessimistic. He felt the odds were about 65 to 35 in favor of an attack. The official was started. He and his colleagues had taken "serious possibility" to mean much lower odds. Disturbed, Kent went back to his team. They had all agreed to use "serious possibility" in the NIE so Kent asked each person, in turn, what he thought it meant. One analyst said it meant odds of about 80 to 20, or four times more likely than not that there would be an invasion. Another thought it meant odds of 20 to 80 - exactly the opposite. Other answers were scattered between these extremes. Kent was floored.

Despite such uncertainty, organizations must institutionalize learning across projects so the impacts of these systemic risks can be reduced, and long-term behavioral improvements can be realized.

Collective learning

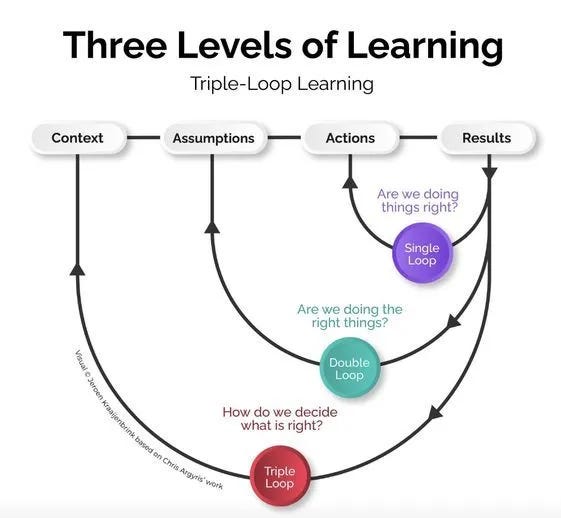

Peter Senge describes the landscape in which this collective learning must unfold. The simplest form of Senge's organizational learning is called single-loop learning and involves providing appropriate feedback to members of an organization within their established, accepted, prescriptive practices. A more powerful form of learning is called double-loop learning and requires teams to recognize and reflect on the patterns of behaviors that arise under particular circumstances. Double-loop learning is particularly important in influencing teams to 'learn how to learn'.

In their book Becoming a Learning Organization, Swieringa and Wierdsma introduced an even more advanced concept they called ''triple loop learning'' (Figure 2), which involves an open inquiry into underlying why's “…that permits insight into the nature of the paradigm itself.” Research has subsequently highlighted that there are many different interpretations of this concept, though providing adequate justification for believing the change is likely (rather than just possible) would seem essential.

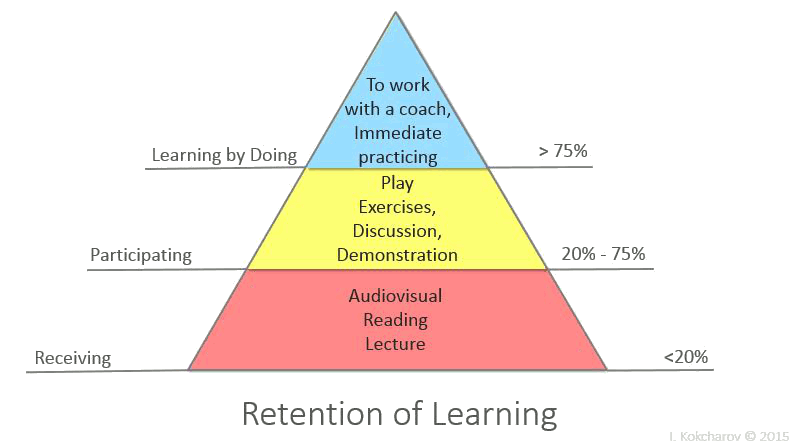

To create such an environment, actors must have opportunities to learn in a variety of situations and understand the behaviors they produce adequately so that causes can be connected to effects, and more informed decision-making can be orchestrated. As figure 3 shows, research in experiential learning has demonstrated that knowledge transfer in the form of oral presentations is effective less than 20% of the time. By creating situations in which students are more engaged in their learning experiences, the likelihood of successfully transferring knowledge can increase to an average of about 50%. But when students can learn by doing (and especially by deciding) and are presented with opportunities to try out ideas in a safe environment, the odds of knowledge transfer nearly triple from what is expected from a passive receiving experience.

As Ray Madachy, the author of the book Software Process Dynamics, observes:

For organizational processes, mental models must be made explicit to frame concerns and share knowledge among other people on a team. Everyone then has the same picture of the process and its issues. Senge and Roberts provide examples of team techniques to elicit and formulate explicit representations of mental models. Collective knowledge is put into the models as the team learns. Elaborated representations in the form of simulation models become the basis for process improvement... Models can be used to quantitatively evaluate the software process, implement engineering, and benchmark process improvement. Since calibrated models encapsulate organizational metrics. organizations can experiment with changed processes before committing precious resources.

Call to action

Understanding is not a one-time insight but an ongoing discipline. In communities where culture rules and constraints compound, the only path forward is through shared inquiry. So the next time you’re ready to prescribe a fix, ask instead: What’s being asked of me? Because action without understanding is like engineering without measurement: ambitions without achievements.

Coming attractions

The articles in this series demonstrate the potential power of using management simulations to provide just such a capability. These simulations can be helpful in aligning the unique perspectives of stakeholders and give them opportunities to try out alternative decisions in realistic project situations. This gives these stakeholders opportunities to connect the dots across time and space. Each article walks through a scenario that is relevant to systems and software engineering practice and provides a series of 'runs' which reveal the performance of the simulation over a project's lifecycle. Team members can interact with these simulations at discrete time intervals that align with typical decision points, rather than trying to connect cause and effect across selected periods. Simulation participants can also be organized into small teams to introduce competition into the exercise and give each of these teams the opportunity to collectively talk through what they believe is happening, based upon the simulation outputs within that session.